Recycling 3.0 & The Dilemma Of Microplastics

In marine environments from lakes to oceans, plastics are the most abundant type of pollutant. As plastic waste is exposed to the elements, it eventually breaks down and fragments into 5 mm particles called “microplastics.” With the prevalence of microplastics, well-intentioned efforts to recycle may be only addressing a small portion of the plastics problem. We’ve come to a moment in time in which our ability to absorb plastics has reached a new plateau: recycling 3.0.

Last March, the United Nations Environment Assembly approved a historic agreement to forge a global plastics treaty by the end of 2024. Seeing countries agree to seek a treaty covering the whole life cycle of plastics was a very positive sign, says Kara Lavender Law, an oceanographer at the Sea Education Association, which provides a semester at sea for undergrads. On tall sailing ships, they collect plastics in places like on the Sargasso Sea. “I have to say, I’m the most optimistic I’ve been since working in this area for probably 15 years.”

Disposal of plastic waste is a serious environmental problem that we face today. Several countries now have active examples of recycling.

- The city of Curitiba in Brazil recycles over 70% of its waste while providing jobs for its poorest citizens, whose plastic collections are exchanged for transport and food tokens.

- 96% of Austria’s population separate their waste into recyclable categories.

- Not only is recycling in Vancouver really important, food scraps are banned from the standard waste bins and must be deposited in a green compost bin.

- In Wales 17 out of 22 councils have waste sorted by residents; in the rest of the councils, the waste is sorted by the council.

- San Francisco’s recycling scheme has 3 different categories: compost, recycle, and landfill.

- Zürich offers 12,000 different recycling points.

- Singapore has some of the lowest usage of landfills in the world, as companies in this country are fully responsible for the waste they produce and how they dispose of it.

- South Korea has 95% of the country reduce their food waste with a food waste fee — households pay a small monthly fee for each bag of biodegradable food scraps.

- Zero Waste Leeds in the UK not only recycles a wide range of waste, it also reuses unwanted items and creates articles and tips for recycling.

These efforts are clearly important in the overall imperative to remove plastic pollution from the environment. Each should be commended for its wherewithal, tenacity, and hope. Unfortunately, they are not robust enough to address microplastics that have invaded our soil, oceans, and bodies. A much more robust recycling 3.0 approach is needed if we are to mitigate the ecological consequences of these hazardous substances.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Understanding the Lifecycle of Plastics

Tracy Mincer is fascinated by how living organisms interact with one another, self-assemble into stable communities, and drive geochemical stoichiometry. He spoke to a group of us in southeast Florida about a subset of his research: the many facets of plastic debris in the ocean.

The assistant professor of biology/biogeochemistry at the Harbor Branch, Florida Atlantic University, leads a research group which explores: 1) The fate of plastic debris in the marine environment and its implications for human health; 2) The chemical cues that drive microbial interactions, the applications of these molecules toward the discovery of chemotherapeutics, and a deeper understanding of microbial chemical ecology.

Plastic particles were first observed by scientists in the oceans in the early 1970s, Mincer began. Guidelines released in 1974 suggested development of polymers that are more water-soluble, non-atmospheric, and non-polluting. Today, while plastic is of “immense utility” to humanity, 33 billion pounds of plastic escapes collection systems and, ultimately, are released into the environment.

“Freshwater plastics were found in places like Minnesota, the land of 10,000 lakes,” Mincer revealed. With few natural buffers, these lakes “were the first to sound the alarm.”

Then there are rivers that collectively dump anywhere from 0.47 million to 2.75 million metric tons of plastic into the seas every year, depending on the data used in the models. The 10 rivers that carry 93% of that trash are the Yangtze, Yellow, Hai, Pearl, Amur, Mekong, Indus, and Ganges Delta in Asia, and the Niger and Nile in Africa.

“Everything flows toward the ocean,” Mincer continued, saying, “it’s important to create plans to capture these plastics before they get taken out to sea.” At sea, plastics break up; when they become small, they seem like food to birds, fish, and plankton.

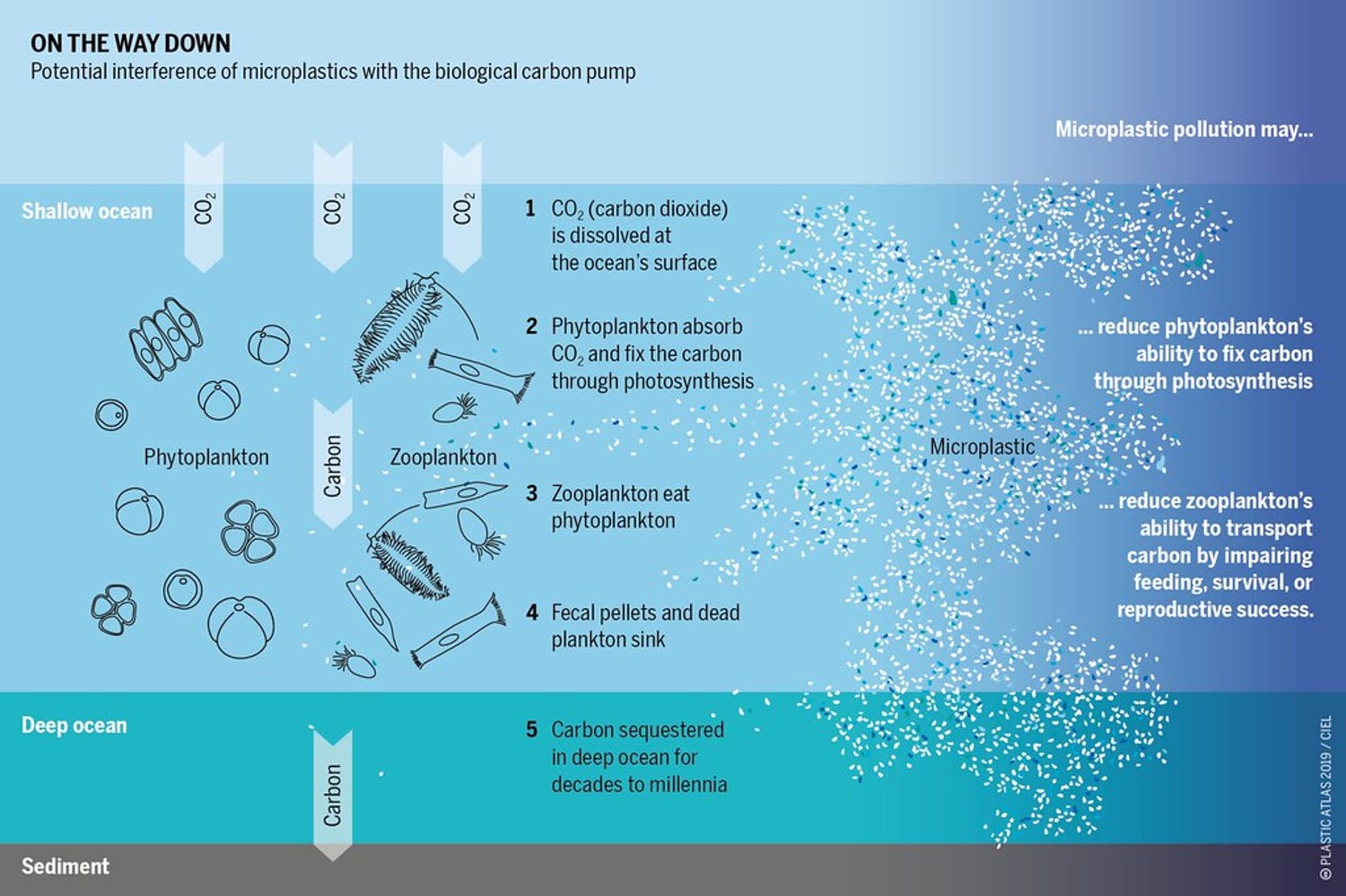

Plus, as plastics break down, small elements can be accreted into the coral, becoming part of their digestive system — pieces of plastic are getting intertwined into the carbonaceous cycle of corals. Plastic ingestion likely also affects fish reproduction. “Plastics can move their way into gonad tissue and influence fecundity rates.”

Most plastics remain in the swash zone, so “beach cleanups really matter.”

Can’t recycling help? Most plastic simply cannot be recycled, a 2022 Greenpeace USA report concludes. US households generated an estimated 51 million tons of plastic waste in 2021, but only 2.4 million tons were recycled. Problems with recycling exist partially due to the various colors and types that attract attention at the time of purchase. “Multicolored plastics are hard to sort,” Mincer explains, so companies with a recycling 3.0 perspective are looking at robotics.

Plastic additives comprise substances that serve numerous purposes in the plastic industry, such as assisting to mold plastics. However, these additives and non-polymerized monomers may be released throughout the entire life cycle of plastics, posing risks to the environment and, ultimately, human health. “Plastics that might be used for renewable energy, but additives are pesky,” Mincer says. “These polymers are quite stable and difficult to break down.”

“Microbes are biodegrading the plastic. Pathogens are adapting to the sea, living on the plastics,” Mincer continues. Plastics seem to stay in the water column for about 10 years, “so, if we stop putting plastic into the ocean, it would clean itself.”

Humans as well as marine creatures are ingesting microplastics. “Tiny plastics that are showing up in crops and other places can be uptaken by plants into their tissues. It’s probably where it’s coming from in our diets,” Mincer notes. “Sea salt could have amounts of very small plastics. Microplastics have been found in beer. There have been lots of publications in this area. As plastics get small, in a 10 or 20 nanometer area, they’re quite toxic if they’re positively charged.” “

How are these microplastics affecting human health? “We don’t know what happens to these small particles when they’re in our body,” he admits.

While Mincer says “it’s hard to study nanoplastics,” he hasn’t given up. “My lab is trying to solve these problems. We’re trying to use ultrasound, to try to see what kind of plastics they might be, but there’s a lot still to be developed.”

Final Thoughts about Recycling 3.0 & Microplastics

With current plastic production and the growing problem of global plastic pollution, an increase and improvement in plastic recycling is needed. Yet additional research suggests that plastic recycling facilities could be releasing wastewater packed with billions of tiny plastic particles, contributing to the pollution of waterways and endangering human health. Evidence of microplastic wash water pollution suggests it may be important to integrate microplastics into water quality regulations. Additional filtration to remove the smaller microplastics prior to wash discharge may be a start to remediate microplastics from wash water, says Mincer.

If you’d like to read some of Tracy Mincer’s research, check out this white paper on the South Atlantic Gyre.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.