Adventures In Missing The Point: Addressing Assumptions People Make About Flyvbjerg’s Work

Over the past week I’ve been digging into various of the topics that Professor Bent Flyvbjerg (Linkedin, Twitter) and I discussed in our excellent 90 minutes together. He and Dan Gardner’s much recommended new book How Big Things Get Done: The Surprising Factors That Determine the Fate of Every Project, from Home Renovations to Space Exploration and Everything In Between is dropping February 7th, so it’s been timely. I’m pleased to note that there’s also an Audible version of it.

As a reminder, Flyvbjerg and Gardner reached out to me about a year ago to request permission to include material I’d been iterating for a few years, a look at the natural experiment of wind, solar and nuclear deployments in China. I was delighted to say yes, but can unequivocally say that my recommendation of this book would be equally strong without my material being in it.

Having estimated, planned, run, and fixed major technology and transformation projects on multiple continents in my career, both failing and succeeding, this book should be read carefully by everyone involved in estimating, planning, approving, choosing between, and delivering projects. And focused as I am in my new career as a decarbonization strategist who guides investors, boards, policy makers, and startups through the thickets of our rapidly changing world, this book should be read carefully by people considering their strategic investments of time and resources.

But that all said, the reactions to my pieces and more generally to Flyvbjerg’s work have been illuminating. This article highlights a few trends in the remarks, and points out some of the rules of thumb Flyvbjerg and Gardner pulled together to ensure that no one is left with the assumption from my brief pieces that it’s a one-dimensional perspective, or that their favored aspect of project or program management is not considered.

One of the obvious things, in retrospect, was that Sinophobia reared its ugly head. Many of the comments on the articles themselves or on LinkedIn (my primary social media hangout) were focused on the ugly aspects of China, not the material. Frequently, they missed the point of the natural experiment on nuclear, wind, and solar being enabled by China’s more centrally planned economy, and greater ability of the national government to override local NIMBYism, regulatory variances and to squeeze out the corrupt profit-takers. Complaints of nuclear advocates related to western public fears and over-regulation are washed away, leaving only the technologies and their ability to be deployed behind. And wind and solar outstripped nuclear in relative and absolute terms, exceeded targets substantially and are continuing to accelerate despite the programs having started a decade after the nuclear program, which remains slow-moving and not meeting its targets.

This is not to suggest that China’s governance model is appropriate for the west or that it doesn’t have significant downsides. That remains beside the point. But for those interested in that subject, I strongly recommend Kishore Mahbubani’s Has China Won?, Zak Dychtwald’s Young China and Ray Dalio’s Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order for some much needed perspective that is often missing.

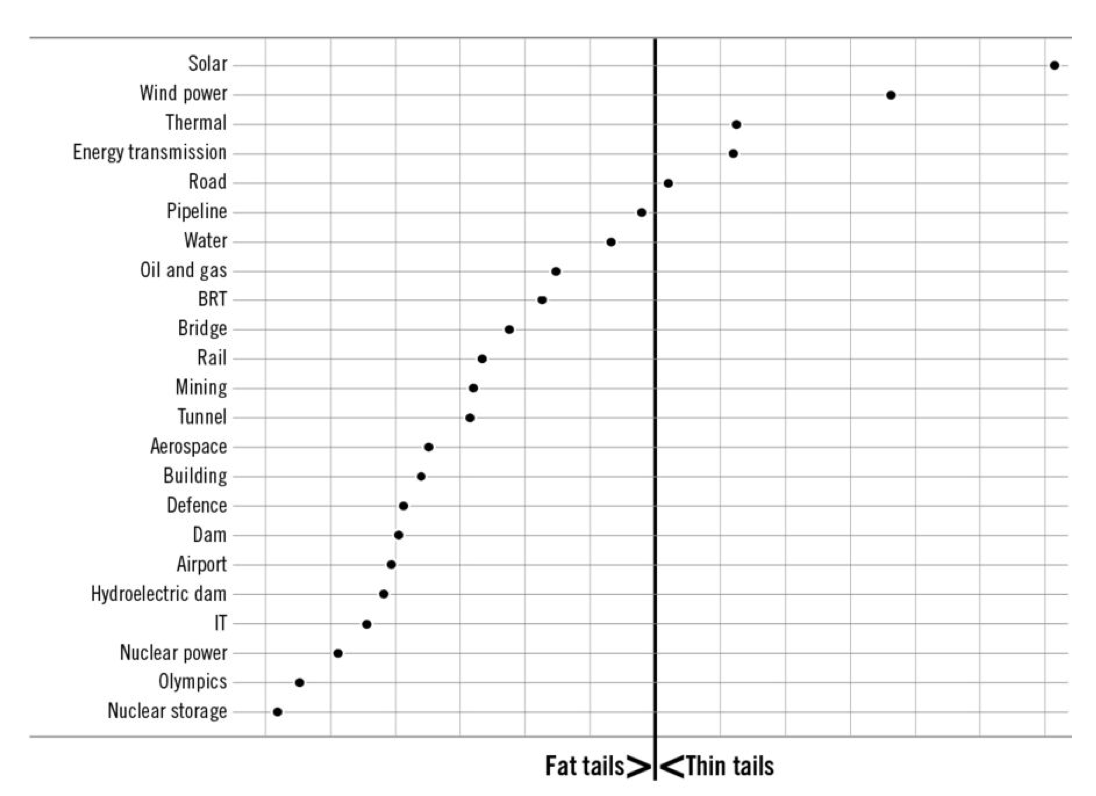

I continue to use this graphic in these pieces because it’s so insightful. It’s from the dataset of 16,000 or so projects Flyvbjerg and team have assembled quality data for. It shows which projects are much more at risk of cost overruns and which are less at risk, based on a statistically significant, mostly global data set. (Getting data for individual Chinese projects remains difficult.) I consider this the most important graphic from the book, and that it and the Coda of rules of thumb should be pasted to planners’, strategists’, policy makers’, and investors’ walls around the world.

And this brings us to the next set of reactions. Nuclear advocates really don’t like this chart, and will find any excuse to ignore or reject its lessons. Frequently, the same people missing the point of the natural experiment material will turn around and say that it is the fault of excessive regulatory zeal or Greenpeace or unwarranted terror of radiation whipped up by the American and Japanese movie industries. As I’ve written elsewhere, it’s the economics, not the fears.

Another group rejects one of Flybjerg’s primary injunctions, think slow and act fast (which I assume was seriously considered as the title or subtitle of the book, and is called out as a rule of thumb in the Coda), in favor of the just start and build a dream model. But Flyvbjerg demolishes that argument. He leans into economist Albert Hirschman’s very influential paper from decades ago that argued that planning was a bad idea, surprising creativity sees us through big projects, and that big thinkers should just do it. As Flyvbjerg notes, either Hirschmann was right or Flyvbjerg is right. There is no middle ground. What Hirschmann and others such as Gladwell, Brookings Institute, and Sunstein ignored was survivor bias, the absurd cost and budget overruns, and the failure to deliver any promised benefits of this credo. Chapter 7, “Can Ignorance Be Your Friend?,” deals with this deeply held and promoted misconception, leveraging examples as diverse as Jimi Hendrix’ custom-built studio, the Sydney Opera House, Frank Gehry’s architectural masterpieces and the movie Jaws. Anyone trying to argue against Flybjerg’s thesis needs to read and understand this chapter.

Others complained that I didn’t write about the essential requirement of having an experienced team. Well, they are correct. I wasn’t making that point, and not trying to write a comprehensive book review, but exploring specific aspects of our conversation in more depth. But assuming that Flybjerg doesn’t cover that as a result is a remarkable leap, yet innumerable people did the hop, skip, and a jump of logic required. In fact, for both the highly successful Madrid subway and Heathrow Terminal 5 projects, Flyvbjerg calls that out as a key condition for success of those programs. The planners intentionally thought slow about project risks, understood broad team and contractor alignment and cohesion was critical, and did extensive work to ensure that very predictable fat-tailed risk didn’t negatively impact their projects. Chapter 8, “A Single, Determined Organism,” is devoted to this subject.

Megaproject and infrastructure deployment consulting organizations such as the excellent Vision, with its focus on commitment-based management, lean heavily into this aspect of successful programs. (Note: a regular collaborator of mine works with Vision on projects in North America and Europe, and has helped me understand and adopt the basics of their approach.) But me not mentioning this aspect when I’m discussing high-speed rail vs transmission project variances, why small modular reactors are unlikely to find an optimal point on the physics vs modularity continuum, or the Iron Law of Projects being that only 0.5% achieve schedule, budget and benefits targets doesn’t mean Flyvbjerg doesn’t address this at length in the book, or that I’m unaware of it.

A few years ago, I had this conversation with the woman who taught me more about fixing troubled projects than the vast majority of people have ever learned, Sharon Hartung, the global technology firm project executive who was absurdly good at it. (Sadly, she passed prematurely recently, but her memory lives on among the people who respected and loved her.) I was pressing her on exactly this point: “How much of it is the team?” Her role at the time required her to lean into the process aspects, and Sharon was excellent at delivering on global strategies for the firm, so this was uncomfortable for her. But we agreed. The team was a huge percentage of the reasons for success, both getting the right people and ensuring that they were aligned and managed for success.

And Flyvbjerg has a specific rule of thumb on the Coda, Get Your Team Right. As Flyvbjerg says, “This is the only heuristic cited by every project leader I’ve ever met.”

Other commenters were remarkably arrogant, claiming that they had perpetual successes in projects, and that whatever point I happened to have been writing about was something that didn’t apply to them. It’s possible that they are correct. There are extraordinary people out there who know how to get big things done and keep proving it. When I was working for a major Canadian bank on a massive branch technology transformation — 1,400 physical locations, 32,000 computer devices, completely new networking infrastructure and telecommunications, retraining 50,000 branch staff — the bank hired one of the biggest technology infrastructure service firms in the world and got Al Eade, a guy who had spent his entire career doing this, over and over. I learned absurd amounts from Eade over the course of that program, and ended up as one of the top three managers of the process with him and another employee. Without Eade or someone with his deep experience driving the slow thinking for 2.5 years, the 10 months of deployment without branch interruptions, with approaching 100% branch satisfaction ratings and running on budget would not have occurred. (Yes, I’ve been lucky many times in my career to work with extraordinary people on extraordinary projects.)

And Flyvbjerg addresses that as well, with the rule of thumb Hire A Master Builder. He draws examples of this out as well in preceding chapters. The Coda, Eleven Heuristics for Better Project Leadership is an excellent reminder of how to succeed in projects.

And so I come to the end of yet another moderately lengthy piece on the book having only scratched the surface of its wisdom and insights. There are eleven rules of thumb in the Coda, and I’ve written about perhaps three or four of them here. I urge people thinking about Flyvbjerg’s work who are asking themselves, “But what about this critically important aspect of project success?,” to not assume that it isn’t covered deeply, well, and in context of other factors. Withhold judgment. Get the book. Find out that you are likely incorrect in that assumption.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.