Australian Mining — Can It Power All The New EVs?

With all the talk about batteries and the materials that are needed to produce them, my thoughts turned to the Australian mining industry and its capacity to fulfill that need and thus power the electric vehicles of the rEVolution. We are already the largest exporter of lithium in the world and have the largest lithium mine in the world. But what of the other minerals needed? I am focussing on the end of ICE by 2027. The IRA means that battery manufacturing in the US will make this possible in North America, according to a recent Environmental Defense Fund report.

Also, what is in the back of my mind is that Australians have a relatively high standard of living partly funded by our exports of fossil fuels. We have done very well out of the Russian invasion of Ukraine as far as exports of coal and gas are concerned, and we are set to get high prices for our wheat exports as well. Sad, but true.

How will our lifestyles survive the global transition to renewables? Will we be able to export enough future facing commodities — that is, battery minerals (and possibly green hydrogen) — to make up the shortfall as our export partners (all committed to net-zero emissions) stop buying our coal?

Each quarter, the Australian government produces a report from the Department of Industry Science and Resources, Office of the Chief Economist. The projections discussed in the rest of this article are from the March 2023 Resources and Energy Quarterly. It is 175 pages long. I have focused on the sections dealing with copper, nickel, zinc, and lithium.

The Australian mining industry represents approximately 14% of GDP (gross domestic product). It makes up more than two-thirds of Australia’s exports and directly employs over a quarter of a million people. Our top five export markets are China (over 50%), Japan, South Korea, India, and Taiwan.

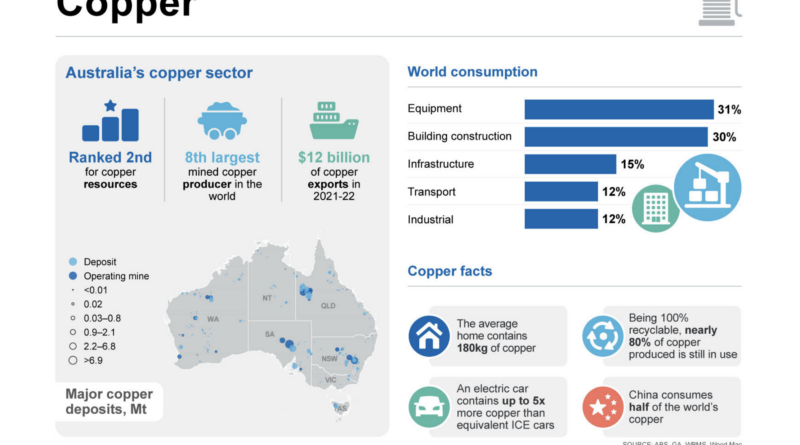

Australia is one of the top five exporters of copper, after Chile, Peru, and Indonesia and Kazakhstan (tied). By 2028, copper prices are projected to grow as demand from the energy transition outweighs future production growth.

“Australia’s copper exports are projected to grow from 868,000 tonnes in 2022–23 to around 970,000 tonnes in 2027–28, supported by additional production from new mines and mine expansions. As output grows and prices strengthen, Australia’s copper export earnings are projected to grow — from $13 billion in 2022–23 to $15 billion (in real terms) in 2027–28.”

Much of this growth in consumption will be led by the proliferation of electric vehicles and the charging infrastructure they depend on. “Sales of EVs approached 11 million in 2022 (up 60% annually). EV sales are projected to grow three-fold to around 30 million units by 2028. The proliferation of EVs also necessitates significant growth in public and private charging infrastructure; by 2030, 10% of refined copper consumption will be accounted for by use in EVs, batteries and charging equipment.” I believe that the threefold increase is too conservative. I would expect it to be closer to 80 million EV units by 2028. Interestingly enough, on page 148, the report predicts EVs will grow tenfold by 2030.

An EV contains 5 times the amount of copper than an ICE-equivalent vehicle contains. As well as EVs, there will need to be copper available for electricity generation and transmission. China consumes half of the world’s copper.

The predicted shortfall in mined supply could be ameliorated by greater volumes of recycled copper. Currently, recycled copper contributes 30% to end use. A return to 2012’s levels of 35% “would provide the market with the equivalent of 5 large greenfield copper projects. Further, there are non-economic benefits of increasing scrap usage; recycled copper requires 85% less energy than primary production, lowering the emissions intensity of the sector. Reaching higher levels of scrap utilisation will likely require supportive government policies from the major economies at all stages of the recycling process.”

Australian mined production of copper is projected to grow at an average rate of 3.0% over the next 5 years, reaching 927,000 tonnes in 2027–28. One mine alone, Oz Minerals’ West Musgrave project, is expected to add around 41,000 tonnes of copper capacity per year. “While there is a projected fall in Australian output in 2027–28, there are several large projects with a completed definitive feasibility study that could come online near the end of the outlook period. A forecast world copper market deficit and higher prices are likely to incentivise production from these projects, adding a potential upside to production forecasts.”

Expenditure on copper exploration has risen overall since 2010 and is double what was spent in 2013. Australia is ranked second in the world for copper resources, so is in a good position to meet growing global demand.

Australia has 23% of the world’s nickel resources. Nickel has a growing role in the production of batteries, but it is mainly used for stainless steel making. “In 2018, 5% of global nickel consumption was battery demand; by 2022, this had grown to 15%, and is expected to reach 25% by 2028.” Projections of future growth will be impacted by EV battery chemistry preference. NCM (nickel–cobalt–manganese) is slowly giving way to LFP (lithium–iron–phosphate).

“LFP batteries are cheaper and tend to be less prone to thermal management issues than NCM batteries. There are also fewer social licence risks for LFP batteries, given the mining issues that exist for nickel and cobalt. However, NCM batteries are more energy dense, which gives them a weight (and therefore range) advantage over LFP batteries.”

Eight percent of new nickel production is expected to come from Indonesia. “Indonesia’s nickel reserves are exclusively laterite ores, which present technical challenges in refining to battery grade nickel. This increases the energy required and waste material generated from refining; extracting nickel from Indonesian laterites produces about twice the level of waste tailings) relative to comparable sulphide nickel mines in Australia.”

Mined production in Australia is expected to increase 50% by 2028, with several new projects coming online. “With no new committed refinery projects, refined nickel production is forecast to be steady at 105,000 tonnes over the outlook period. That said, several battery metal projects exist that are targeting first production by 2025. These include the Sunrise Project in New South Wales, the Townsville Energy Chemical Hub in Queensland and the WA pCAM Hub in Western Australia. These projects will not increase the volume of refined output, but will move Australia’s nickel output further up the value chain.”

Exploration expenditure for nickel and cobalt continues to increase, up by almost 30% since December 2021. The vast majority of cobalt is produced as a by-product from large-scale copper and nickel mines.

Zinc is described as an emerging battery material. Australia has 27% of the world’s zinc resources and is the 3rd largest producer. It is among the top five exporters of zinc, second behind Peru and ahead of the USA, Bolivia, and Belgium. (Belgium — who would have thought they were a top zinc exporter?) Zinc’s primary use is in galvanised steelmaking.

“The global energy transition is expected to support demand for zinc, due to its role as a key input to wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicles. Spending on the deployment of these technologies is supported by policies such as the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU Green Deal. Developments in zinc battery technology also have the potential to drive additional demand.”

Over the next 5 years, Australian mine output is expected to grow an average of 2.5% per year. High levels of exploration expenditure are expected to lead to increases in domestic production capacity.

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of lithium and is now moving into the refinery space. Its main use is in the production of rechargeable batteries for electric vehicles. Demand for lithium will thus follow the same trajectory as EV uptake. Battery recycling only provides 2% of global supply.

“The EV battery supply chain relies heavily on China, which makes 75% of all lithium-ion batteries, and holds about 70% of cathode production capacity and 85% of anode output. Further, over half of lithium, cobalt and graphite processing/refining capacity is located in China. As countries look to cut their dependency on Chinese imports and develop their own lithium and battery production, export opportunities will rise for Australian producers.”

The answers to the questions I initially proposed seem to be a qualified “yes.” Australian mining is ramping up to play its part in the rEVolution. Industry is moving the minerals up the value chain to expedite the production of battery materials. Export volumes and incomes are on an upward trajectory. State and federal governments can be assured of income from tax and royalties! My pension is safe!

Featured image courtesy of Australia government.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy