Climate Change Is Turning California’s Wildfire Season into Wildfire Year

Like pay phones, typewriters, and VCRs, a wildfire “season” is a thing of the past.

Outside the historical July to October season, we’ve seen wildfires ignite and burn deeper into November, start earlier in the spring, and, in the case of this past winter, we saw Colorado’s Marshall fire burning in December and California’s Colorado fire burning in January.

As spring has begun to unfold across the country, CalFire officials and outlooks from the National Interagency Fire Center suggest that wildfires are likely to ignite earlier than they have historically.

The consequences of this are obvious when looking at trends in areas burned across California (Fig. 1). There is no wildfire season. Wildfires are with us year-round now. But is this normal? And will wildfires across seasons get worse?

Spring wildfires

Climate change has sped up the arrival of spring, with major consequences for wildfires (Fig. 2).

Multiple studies have connected the timing of spring to the extent of wildfire damage, showing that earlier snow melt and higher spring and summer temperatures are correlated with a larger area burned by wildfires. Those shifts give vegetation and soils a longer time to dry out, increasing their flammability.

Fall wildfires

In autumn, higher temperatures and the delayed arrival of rain mean that fuels remain drier and more flammable deeper into autumn. Together these conditions have increased the likelihood of extreme, late-season wildfires.

Winter wildfires

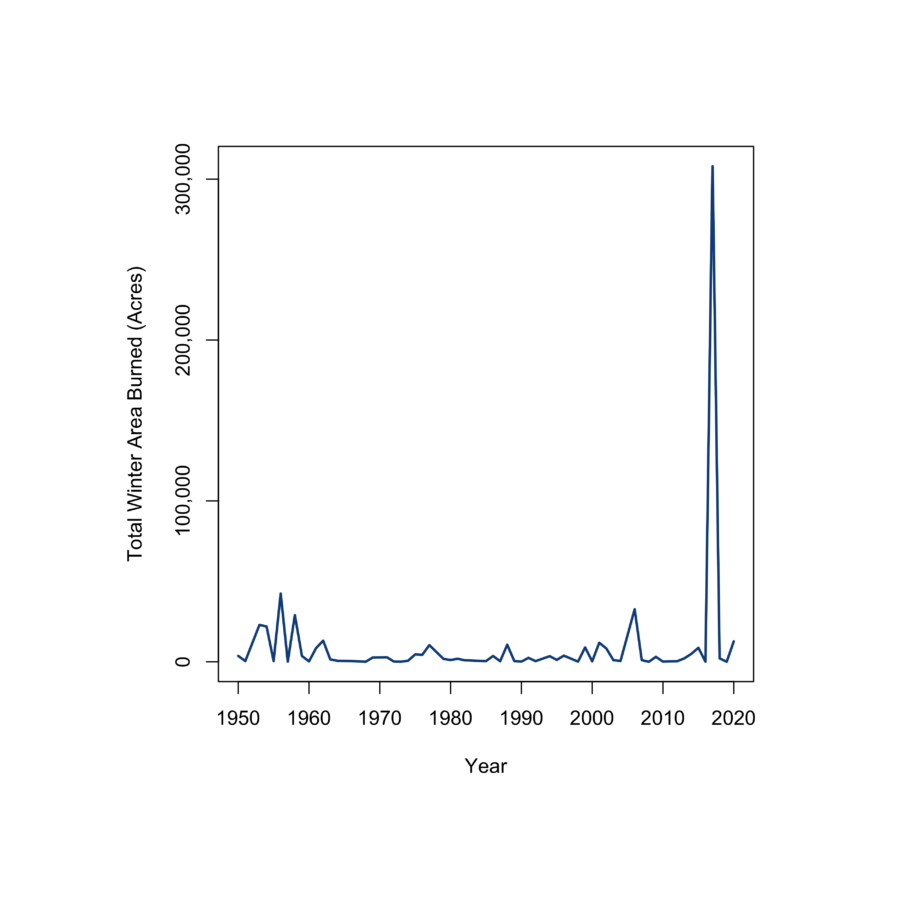

Until 2017, winter wildfires in California didn’t burn much area. Between 1950-2020, an average of 9,923 acres burned annually across December, January, and February (Fig. 4).

In 2017, however, a record number of fires burned during the winter months. The largest of them, the Thomas Fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, burned more than 200,000 acres in Southern California.

The size and timing of such large wildfires in a winter month was unprecedented, but the conditions and mechanisms that led to these wildfires, like high temperatures and delayed arrival of rains, illustrate how climate change can increase the likelihood of extreme events.

What is fueling year-round wildfires?

Climate change has disrupted historical trends and created conditions for year-round wildfires. Forests are roughly 50% drier, and the number of days of high fire danger have increased and are projected to double by the end of the century. This is layered on top of dangerous forest conditions that stem from a legacy of fire suppression and forest management that has increased the amount of vegetation available to burn.

A cycle of climate impacts throughout the year can compound to create dangerous conditions, like we saw ahead of 2017’s unprecedented winter wildfires (Fig. 4).

The winter before these fires, intense rain initiated a burst of vegetative growth in California, meaning fine fuels like grasses and shrubs rapidly produced biomass. This rainy period was followed by an exceptionally warm summer in 2017, which at that point was the warmest ever recorded in California (76.5°F).

High temperatures allowed the vegetation from the previous winter to dry out, creating a landscape primed to burn. An abnormally warm fall and later-than-usual arrival of fall rains further exacerbated wildfire risk by allowing dry vegetation to remain ignitable through December. These conditions, combined with downslope winds (called Diablo winds in Northern California and Santa Ana winds in Southern California), led to the massive spike in burned area observed during winter 2017.

While the simultaneous occurrence of these factors led to unprecedented winter fires in 2017, climate change projections suggest that each individual contributing factor is likely to occur more frequently into the future.

Preparing for wildfires of the future

As humans continue to release greenhouse gases, global temperatures will continue to rise. Hotter summers are likely to continue for California and the state remains under record-breaking dry conditions, with the majority of the state experiencing severe drought.

A 2020 study led by the Union of Concerned Scientists predicted that weather whiplash, or swings between very wet and very dry years, is likely to increase across California. Further, a 2021 study showed that the onset of California’s rainy season is increasingly delayed and that those rains are occurring over a more concentrated period. Together, these studies illustrate how climate change has elevated the threat of wildfires year-round.

In light of this threat, adapting to and preparing for wildfires can help safeguard individuals and communities. Federal and state agencies can increase the area treated with risk reduction activities like prescribed burns, cultural burns, and thinning. Programs like FireWise USA® provide guidance about protecting homes and neighborhoods. Individuals can prepare for smoke impacts by installing air filters, monitoring air quality, and stockpiling protective masks.

Wildfire seasons may be a thing of the past, but learning to live with wildfires is most certainly part of our future.

Data note: Wildfire perimeter dataset (Fire Perimeters through 2020) accessed from California’s Fire and Resource Assessment Program (FRAP).Fires were sorted by their ignition or discovery date. We focused on California due to data availability and quality, particularly for fires smaller than 300 acres.

Originally published by Union of Concerned Scientists, The Equation. By Carly Phillips, Fellow.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.