Canada’s National Projects: Betting on Nuclear & LNG While the Future Waits

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Canada has put a stake in the ground by deciding which megaprojects are now officially in the national interest. Out of an initial list of 32 candidates I analysed recently, five made the cut. That is a small number on paper, but the financial and climate commitments stretch out for decades. When countries make decisions at this scale, it matters to look not at the sales brochures but at the track record of similar projects. That is where How Big Things Get Done author Professor Bent Flyvbjerg’s reference class forecasting comes in. Instead of assuming the estimates are correct, you look at what happened on the ground in the past. What you find, time and again, is that megaprojects are late, over budget, and deliver less benefit than promised. Canada is not immune to that pattern.

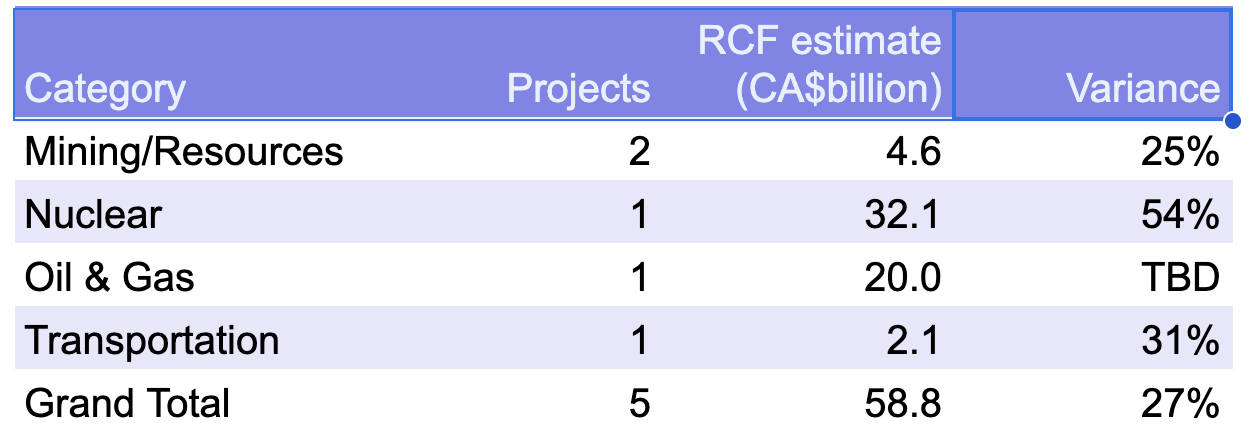

When I apply reference class forecasting to the approved list, the total swells to CA$58.8 billion, roughly a third higher than the official estimates. Nuclear tops the table at over CA$32 billion, with a 54% variance. LNG Canada Phase 2 comes in at CA$20 billion and close to 40% of the total. It’s variance is TBD because I was unable to find any public estimate of costs of phase 2. Mining projects add CA$4.6 billion, with a 25% variance, while the Contrecœur container terminal is CA$2.1 billion, with a 31% variance. Put another way, nuclear and LNG make up almost 90% of the adjusted spend, while the other three are comparatively small. That is not a portfolio that screams balanced commitment to the future. It is a portfolio that reflects a country still hedging its bets on expensive and legacy technologies.

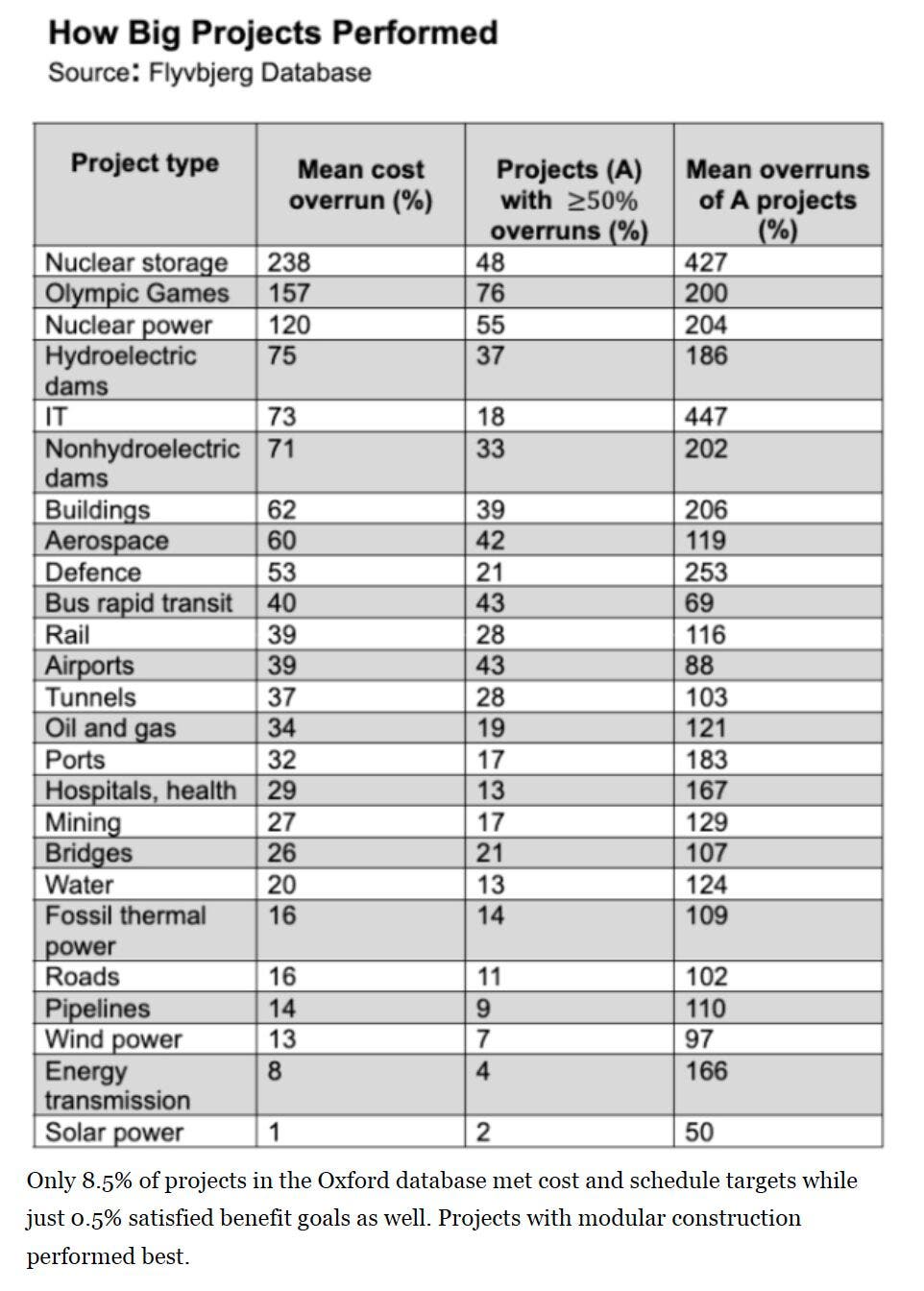

The Darlington small modular reactor is being sold as a milestone. Canada would be the first G7 country to have an operational SMR. The promise is 300,000 homes powered, jobs for decades, and a nuclear supply chain that can be exported. I have no problem with ambition, but nuclear projects have one of the worst track records of any category. Variances are not minor. They are routinely over 50%. Small modular reactors are first of a kind, which means risk is compounded. That does not mean they cannot be built. It does mean the chances of them being built on time and on budget are slim.

LNG Canada Phase 2 is another story. Proponents like to point out that it will be more efficient than other LNG facilities around the world, that it uses hydropower, and that its shipping route to Asia is shorter. That’s only somewhat true, as currently its being powered by natural gas and Phase 2 is planned to start with natural gas, converting only later and partially. But when I looked at Phase 1, the numbers were sobering. Over 50 years, the project will emit 2.2 billion tons of CO2e. Billions in subsidies and tax breaks have already flowed to make it viable. There are tariff exemptions, carbon tax rebates, and provincial credits stacked under the hood. Demand is also far from guaranteed. LNG contracts are usually only a decade or so in length. Global decarbonization is not slowing down, and demand curves may bend in ways that make Kitimat less profitable long before its 50-year horizon.

Bent Flyvbjerg’s global megaproject analysis makes it clear that transmission, wind, and solar projects are the least likely to run over budget or fall badly behind schedule. Their modularity, repeatability, and short construction timelines make them predictable in a way nuclear and LNG projects never have been. That contrast puts Canada’s decision into sharp relief: by designating nuclear and LNG as projects of national interest, the country has chosen the riskiest energy pathways rather than the most reliable and cost-controlled options available.

The mining projects, McIlvenna Bay and Red Chris, are more aligned with what Canada should be doing. Copper and zinc are core to electrification. Claims of the first net-zero copper mine are worth testing, but at least they point in the right direction. Partnerships with Indigenous communities are essential and in place here. The risks are still real. Mining projects face environmental review, tailings challenges, and global commodity price swings. The 25% variance in the RCF numbers is not noise. It is a signal to treat all cost projections with caution. Even so, these projects at least intersect with the materials that a clean economy requires.

The Contrecœur container terminal is in a different category again. It is about trade, not energy. Expanding the Port of Montreal’s capacity by 60% positions Eastern Canada to move more goods and support more resilient supply chains. Container infrastructure has more of a future than fossil export terminals. The 31% variance baked into the RCF estimate is real, but the alignment with diversification and resilience makes this project more defensible. The real question is whether demand will justify the new capacity across the decades it will operate.

When I step back and look at the balance, the picture is not encouraging. The overwhelming share of investment is still pointed toward nuclear and LNG. Nuclear is the category with the longest history of failure to meet cost and schedule promises, and perplexing in a world rapidly spooling up renewables, not nuclear. LNG is most likely to face declining relevance in a world moving toward electrification and lower emissions. The smaller projects in critical minerals and trade infrastructure are aligned with the future, but they are dwarfed by the commitments to the past. That is the opportunity cost of the list. Money and attention poured into megaprojects with a poor record leaves less for transmission, renewables, storage, and interconnectors, which are what Canada actually needs to scale quickly, none of which made the list.

We do not have to look far for cautionary tales. Hinkley Point C in the UK is years late and billions over budget. US LNG terminals are being stranded by changing demand. These are not random outliers. They are the pattern. Reference class forecasting does not predict the future with perfect accuracy, but it gives a range that is based on hard data, not optimism. When Canada designates projects of national interest, it should be clear-eyed about that pattern.

These choices will shape Canada’s economic path and emissions trajectory. They will define whether jobs and GDP are anchored in the sectors that are growing or in those that are contracting. They will test whether our national interest is being defined by climate goals or by the inertia of past industries. The next decade will show whether Darlington’s SMR can be built at anything like its promised cost and schedule, whether Kitimat’s LNG bet holds up against global demand shifts, whether mining projects deliver net-zero copper, and whether Montreal’s container expansion fills with trade that builds a clean economy.

Canada has made its choices for the short list. My analysis is that the risk is high, the balance is skewed, and the opportunity cost is substantial. These projects will be measured not against their launch speeches but against their long-term outcomes. Reference class forecasting tells us those outcomes are likely to be more expensive and less timely than promised. The questions are whether they will still be worth it when the bills come due and whether more major projects that are actually aligned with the national interest will be added to the list over time.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy