Landfill Panic vs System Reality: What Wind & Solar Actually Displace

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Claims about wind turbines and solar panels filling landfills are circulating again, often framed as a rediscovered flaw in clean energy that somehow offsets its benefits. The argument is familiar. Wind turbine blades are large, solar panels contain glass and metals, and at the end of their lives these materials must go somewhere. The implied conclusion is that wind and solar merely trade one environmental problem for another. It is worth taking the claim seriously, not because it is new, but because repeating it without system context obscures what actually matters in electricity generation.

The landfill framing persists because it appeals to intuition. A pile of discarded blades or panels is visible, bounded, and easy to photograph. Atmospheric pollution is invisible, diffuse, and difficult to picture. Humans reason poorly about flows and accumulation, especially when the harm is delayed or spatially separated from the source. This asymmetry in perception explains why solid waste arguments resurface even as the energy system evolves. Visibility is mistaken for scale.

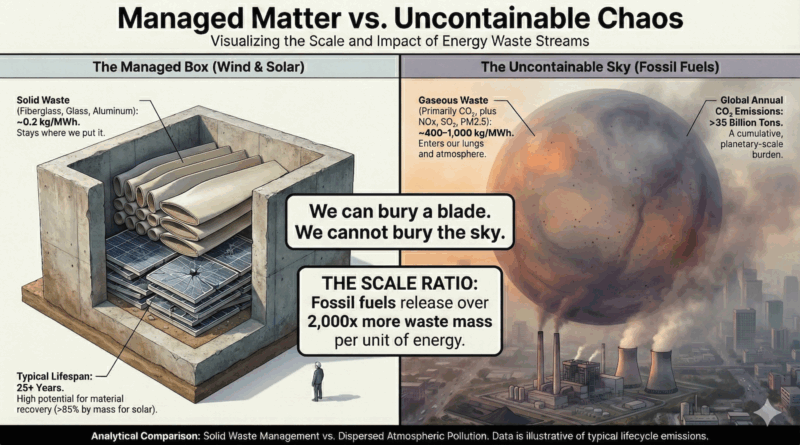

The landfill argument is fundamentally a claim about mass. It asserts that wind and solar create large amounts of physical material that must be disposed of, and that this mass represents an unacceptable environmental burden. Accepting that premise for the sake of analysis, the appropriate response is not to dismiss the metric but to apply it consistently. Electricity systems can be compared on a per MWh basis not only for emissions but also for material throughput. If mass is the concern, then mass per MWh is the correct unit.

When expressed that way, the scale of lifecycle solid waste from wind and solar becomes clear. Modern onshore wind turbines use three blades weighing roughly 13 to 18 tons each, mounted on turbines in the 3 to 5 MW range, operating for 20 to 25 years at capacity factors around 35% to 40%. Annualizing the full blade mass over lifetime electricity production yields on the order of 0.1 to 0.25 kg of blade material per MWh, even under worst case assumptions that all blades end up in landfills. Including other solid materials such as foundations and balance of plant does not change the order of magnitude. Solar photovoltaic systems, with panel lifetimes of 25 to 35 years and steadily falling material intensity per watt, produce similarly small quantities of annualized solid waste per MWh. These materials are inert, contained, and managed within engineered waste systems at end of life.

Coal and natural gas systems operate very differently. They do not produce most of their waste at end of life. They produce waste continuously, every hour they run. Coal generation emits roughly 900 to 1,000 kg of CO2 per MWh at the stack, along with nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, fine particulates, and of course toxic fly ash. Natural gas generation emits less CO2 from combustion, but when upstream methane leakage and methane slip are included, lifecycle emissions rise to roughly 380 to 690 kg CO2e per MWh depending on plant type and leakage assumptions. These are not episodic wastes. They are ongoing mass flows into the atmosphere.

Using the same mass metric that critics invoke, the comparison is stark. Coal emits roughly 950 kg of CO2 per MWh. Wind produces roughly 0.1 to 0.25 kg of annualized solid waste per MWh. That is a ratio of roughly 4,000 to 8,000 times more mass per unit of electricity, even before accounting for other pollutants. Natural gas shows a similar, if smaller, disparity. Even on the critics chosen terms, fossil fuels dominate the material footprint by orders of magnitude.

Mass, however, is still the wrong metric for environmental harm. Harm depends on dispersion, toxicity, persistence, and biological interaction. A kilogram of fiberglass or glass in a lined landfill remains contained. A kilogram of sulfur dioxide or fine particulate matter disperses, reacts in the atmosphere, and contributes to respiratory and cardiovascular disease. A kilogram of CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere for centuries, altering the climate system. Treating these as equivalent because they share a unit of mass is a category error.

This is where displacement becomes central. Wind and solar are not being compared against an empty baseline. Every MWh they generate displaces a MWh from coal or gas somewhere on the grid margin. The landfill argument implicitly assumes no displacement, which is not how electricity systems operate. Ignoring displacement is equivalent to ignoring the system in which the technologies exist. When displacement is included, the comparison shifts decisively. Small amounts of managed solid waste offset large quantities of unmanaged atmospheric pollution.

It is also important to update the numbers. Earlier analyses, including my own, were based on smaller turbines, lower capacity factors, heavier materials per unit of capacity, and shorter assumed lifetimes. Solar panels used thicker silicon wafers and had lower efficiencies. Over the past decade, wind turbine ratings have doubled, capacity factors have increased, material intensity per MW has fallen, and lifetimes have extended. Solar has followed a similar trajectory. The result is that lifecycle material use per MWh is lower today than in the past, and falling further. Arguments that rely on outdated assumptions understate the performance of current systems.

End of life management for wind and solar remains a real topic, but it is a waste management and engineering problem, not a systemic environmental failure. Recycling blades, repurposing panels, designing for disassembly, and extending operational lifetimes are tractable challenges. They scale with installed capacity and are addressed episodically. Climate change and air pollution scale with every unit of fossil electricity generated and compound over time.

The contrast between contained solids and dispersed pollution is the quiet core of the issue. One sits in a managed location and stays put. The other spreads, accumulates, and causes harm far from its source. Focusing on landfill mass without acknowledging this distinction misses what matters most in energy systems.

A serious discussion should therefore focus on improving material efficiency, recycling, and lifetime extension for wind and solar while accelerating their deployment to displace fossil generation. Framing the conversation around visible waste piles instead of invisible but far larger pollution flows does not improve environmental outcomes. It distracts from them.

As wind and solar continue to improve, the landfill narrative will become increasingly disconnected from reality unless it is grounded in system level thinking. The relevant comparison is not whether clean energy produces any waste at all, but whether that waste is comparable to the pollution it displaces. On a per MWh basis, and using the critics own metric, it is not even close. The perfect is the enemy of the absurdly better in every respect.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy