From Optionality to Outcome: How Germany Can Reset Hydrogen Without Losing Face

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Germany now has a pressurized segment of its hydrogen backbone that is physically complete and operationally empty. There are no connected suppliers feeding hydrogen into it, no contracted customers drawing hydrogen out, and no credible near-term pathway to change either of those facts. This is no longer a question of modeling or ambition. Steel is in the ground, compressors are installed, the line is pressurized, and the meters are idle. Major industrial organizations are making it clear that the meters will remain idle and hydrogen for transportation and heating has died on the drawing board. For policymakers and strategists, the relevant question is no longer whether hydrogen can play a role in decarbonization in theory. The question is what Germany should do next, in practice, to protect households, preserve industrial competitiveness, and deliver emissions reductions at the lowest system cost.

This challenge belongs to Germany to solve. Energy infrastructure, industrial policy, and regulated networks sit squarely within national decision making. External analysts and strategists like me cannot and should not dictate outcomes. However, outside perspectives can still be useful when a system reaches a decision point that is hard to navigate politically from the inside. Germany’s institutions are strong, its technical capacity is deep, and its climate ambition is clear.

This guidance is offered deliberately from outside Germany, not to second-guess decisions made under pressure, but to support those inside government, regulation, and industry who are already grappling with how to communicate a necessary shift away from hydrogen maximalism. It is not written for audiences still invested in the hydrogen economy narrative as an end in itself, nor for those whose institutional or professional identities are tightly bound to that framing.

It is written for policymakers, strategists, and influencers who recognize that the next phase of decarbonization in Germany depends on narrowing scope, exercising discipline, and accelerating electrification where it delivers results. Over the next couple of years, transparent and consistent messaging will matter as much as technical correctness. The intent here is to offer a strategic communications lens that can help set aside an economy-wide hydrogen storyline without triggering defensiveness, while giving credible actors inside Germany language they can use to explain a pragmatic reset to different audiences as the transition moves forward.

The path to the current situation was shaped by conditions that no longer apply. After 2022, Germany faced an abrupt loss of Russian gas, volatile LNG markets, and real concerns about supply security. Under those conditions, preserving multiple pathways appeared prudent. Reusing recently built gas infrastructure for hydrogen seemed attractive because it promised continuity, speed, and the appearance of optionality at a time when few options felt safe. That context matters because policymakers will need to explain past decisions without casting them as errors. Many of those decisions were reasonable responses to uncertainty.

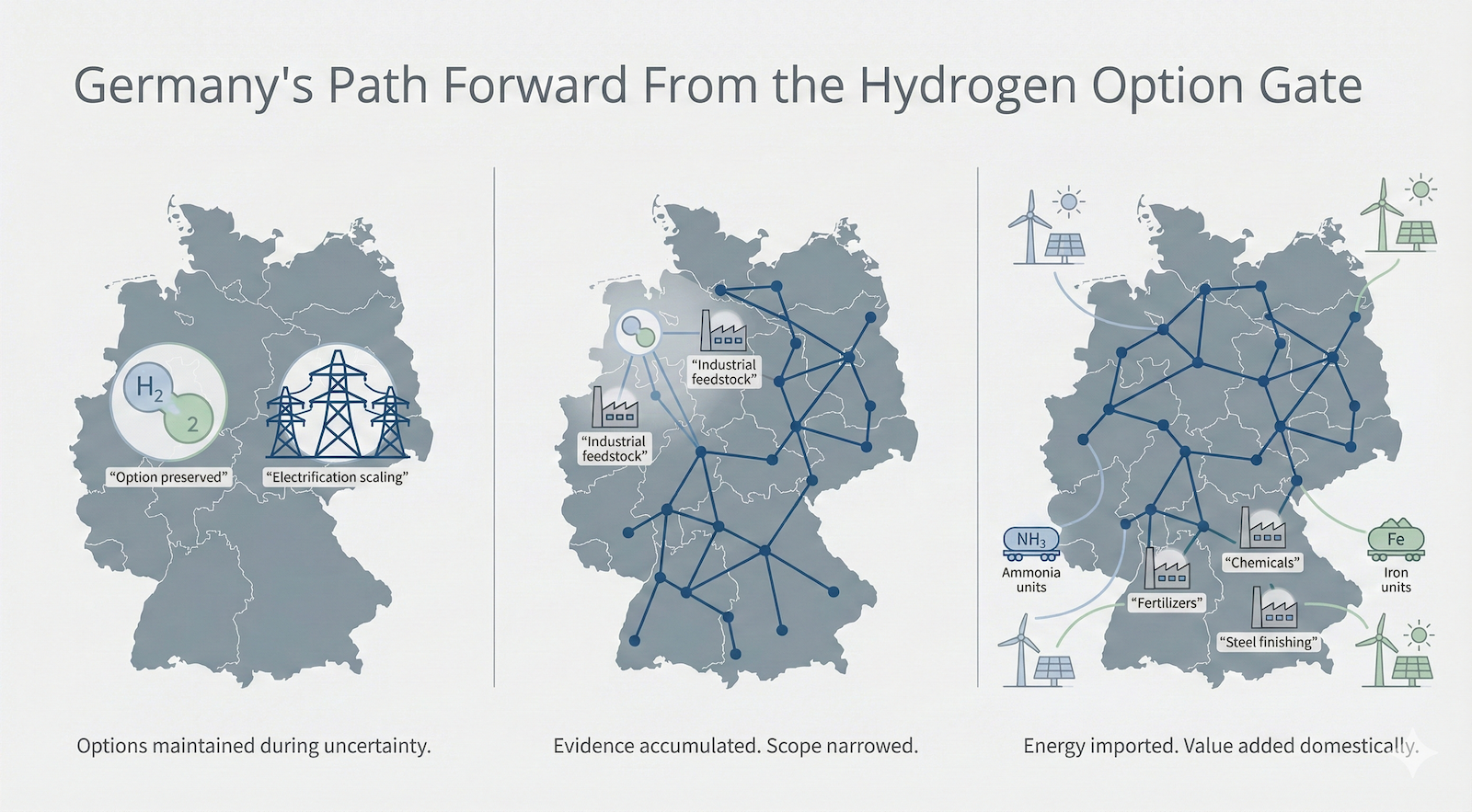

Optionality, however, has a specific meaning if it is to remain credible. Preserving an option is not the same as committing to it. Optionality is a temporary state that exists to gather evidence. It only works if there is an explicit or implicit decision gate, a point at which accumulated information determines whether an option is exercised or closed. For policymakers and strategists, framing the current moment as the arrival of that decision gate is essential. It signals competence rather than reversal. It tells institutions and markets that strategy is adaptive rather than frozen.

The evidence that has accumulated since the hydrogen option was preserved is now sufficient to support a decision. Green hydrogen supply remains expensive relative to alternatives. Even the most optimistic projections for domestic electrolysis struggle to get below $4 per kg delivered, with electricity inputs of roughly 50 to 55 kWh per kg before compression and transport. At German wholesale power prices, that embeds high marginal electricity costs into any hydrogen molecule. Demand has not materialized at scale. Industrial buyers that have flexibility continue to favor electrification or imported feedstocks. Domestic targets for electrolyzer deployment are slipping because of cost, permitting, and offtake uncertainty. At the same time, electrification has moved faster than expected in transport, heating, and industry, and grid capacity has become the binding constraint. This evidence could not have been fully known in 2022, although many aspects of it were clearly obvious to analysts not invested in the hydrogen narrative, but it is visible now and can be leveraged.

For technical audiences inside ministries and regulators, it is important to explain clearly why the existing pipeline cannot anchor demand retroactively. The segment that has been built is oversized for realistic industrial hydrogen volumes, routed through regions without concentrated anchor demand, and disconnected from low cost supply. Hydrogen demand does not appear because a pipe exists. It appears when the delivered cost is competitive with alternatives. Without that condition, waiting does not improve outcomes. It simply increases the time during which regulated capital earns returns without delivering service.

For finance ministries, consumer advocates, and energy regulators, the most important point is that doing nothing is not neutral. Regulated infrastructure earns allowed returns whether or not it is used. If an idle hydrogen network is treated like a fully utilized one, costs flow through tariffs and eventually into electricity bills. A 400 km segment built with roughly 320,000 tons of steel represents embedded capital that does not disappear if molecules do not flow. Allowing that capital to drive future subsidies or forced demand creation is the most expensive path available.

The only face saving move available at this point is to be explicit that optionality was preserved through a period of uncertainty and that the option has now been closed because it did not pass the decision gate. This framing matters for political leadership, for civil servants, and for industrial stakeholders. It allows past actions to be described as prudent hedging while making present actions appear disciplined. The sentence policymakers need to be comfortable saying is simple. Optionality was preserved. The option has now been evaluated. The system outcome does not support exercising it.

That framing also allows the existing pipeline to be repositioned without pretending it will soon be useful. The steel in the ground can be described as a contingency asset rather than a backbone. It preserves a theoretical option under extreme future conditions, but it does not justify further expansion. This language matters for regulators and TSOs because it decouples asset existence from growth obligation. It allows depreciation, maintenance, and safety to be managed without committing additional capital.

A pragmatic reset needs to be explicit about both scope and direction. Hydrogen remains appropriate as an industrial feedstock, but only within a shrinking and clearly bounded set of uses. Refinery demand, which historically accounted for a large share of German hydrogen consumption, will decline steadily as oil throughput falls and fuel production electrifies. Chemical sector demand persists, but at limited volumes that do not justify an economy-wide hydrogen system. Beyond these uses, hydrogen is relevant only for a small number of industrial processes that cannot yet be electrified at acceptable cost. Hydrogen exits the role of general energy carrier for heating, power generation, and transport. Network expansion shifts from aspirational planning to contract-led development, with binding offtake and supply commitments as a precondition. Speculative demand risk is no longer carried by households or electricity consumers, and the regulated system reflects that boundary clearly.

Applying the same logic to ammonia and iron is essential for industrial and political credibility. Green ammonia and green iron are both energy-intensive intermediates whose costs are dominated by electricity. Producing them domestically at scale would embed high German power prices into globally traded commodities, eroding competitiveness without preserving commensurate value. Importing low-carbon ammonia and low-carbon iron units from regions with structurally lower renewable costs avoids that outcome while strengthening, rather than weakening, Germany’s industrial base. Fertilizer formulation, blending, and distribution remain domestic. Explosives and blasting agents remain domestic. Chemical derivatives and downstream processing remain domestic. In steel, importing green iron while retaining steelmaking, finishing, and advanced manufacturing preserves high-skill employment, technical leadership, and margins. The most energy-intensive, lowest-value steps occur where electricity is cheapest, while Germany retains the regulated, capital-intensive, and knowledge-rich segments that define long-term industrial strength.

This framing works for industrial firms because it reduces uncertainty. Instead of betting on subsidized domestic molecule production with unclear long term economics, firms can plan around electrification, imported feedstocks, and stable electricity markets. It provides clarity on where government support will and will not flow. It aligns investment signals with cost reality.

It also works for households and voters because it centers bill protection. Redirecting capital away from underutilized molecule networks and toward grids, storage, and electrification lowers long term electricity price volatility. It avoids a repeat of fuel price shocks that reprice the entire economy. For a household paying for heat, mobility, and electricity, this distinction is tangible even if the technical details are not.

Climate focused audiences also need a clear explanation. Electrification delivers emissions reductions with far fewer losses. Using electricity directly avoids the 30% to 70% energy penalties associated with hydrogen pathways. Focusing on least cost decarbonization accelerates emissions reductions within existing carbon budgets. Narrowing hydrogen use increases climate credibility rather than reducing it.

The reset must be paired with a visible affirmative program. Grid expansion, distribution upgrades, faster interconnection, heat pump deployment, industrial electrification, storage, and flexibility must be described as the core of the energy transition. These investments reduce emissions, reduce bills, and reduce geopolitical exposure at the same time. Hydrogen and ammonia become supporting tools rather than pillars.

Geopolitics should be used as context rather than cover. Dependence on imported molecules recreates vulnerability, even if those molecules are low carbon. Domestic electricity reduces that vulnerability. Industrial competitiveness increasingly tracks access to reliable clean power rather than access to alternative fuels. This is not retreat. It is alignment with global reality.

Communication discipline will determine whether the reset succeeds. Policymakers need to lead with the physical reality of the pressurized but unused pipeline. They need to explain optionality clearly. They need to state that the decision gate has been reached. They need to describe how risk will be shifted away from households. And they need to show where investment is going instead. Avoiding defensiveness matters more than defending any individual asset.

By the early 2030s, success should look unremarkable. Hydrogen is used where it makes sense and nowhere else. Ammonia is imported as a feedstock and converted domestically into higher value products. Scrap steel is expanded and green iron imports should be starting to displace high emissions domestically produced hydrogen. Electricity prices are less volatile. Grid constraints are easing. Emissions are falling steadily. The system works, even if it looks different than earlier visions suggested.

Adapting strategy when evidence arrives is a sign of institutional strength. Germany’s challenge now is not technical feasibility but narrative discipline. The tools to shift the needle away from unproductive hydrogen use and toward electrification already exist. The task for policymakers and strategists is to use them in a way that protects credibility, households, and industrial capacity at the same time.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy