When Steel Outlives Strategy: The Climate Cost of Germany’s Hydrogen Pipeline

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Germany’s 400 km hydrogen backbone segment is now pressurized, full of fossil hydrogen, and waiting. There are no meaningful suppliers connected to it and no contracted offtakers drawing molecules out. That fact alone makes it worth slowing down and doing the accounting carefully, because large infrastructure decisions do not become climate positive by default simply because they are relabeled. They only become climate positive if they deliver real decarbonization outcomes that exceed the emissions locked into their materials, construction, conversion, and operation.

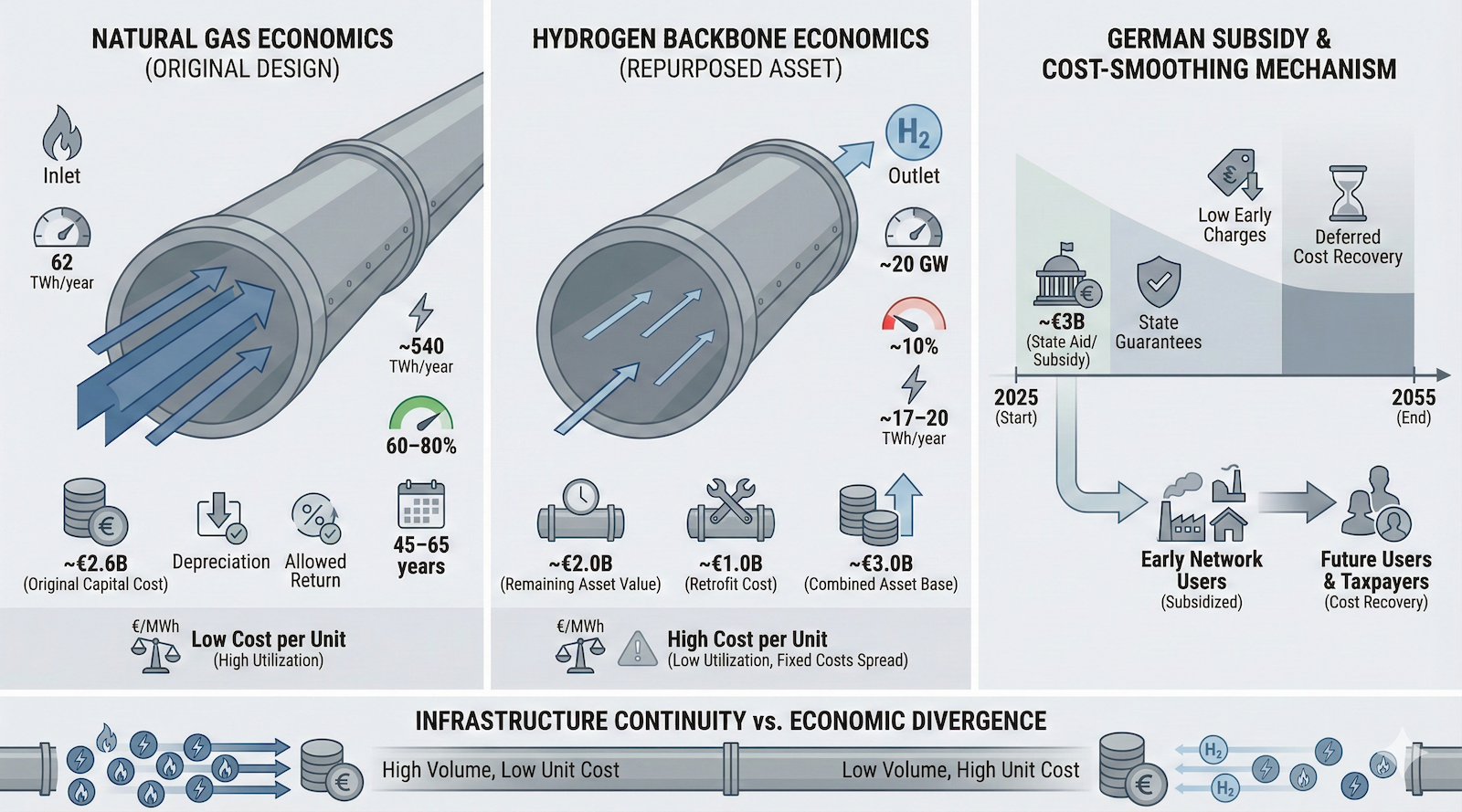

This pipeline did not begin life as a hydrogen asset. It was built around 2020 as a large diameter natural gas transmission pipeline, roughly 1.4 m in internal diameter and around 400 km long. It was conceived during a period when German energy planning still assumed decades of continued high natural gas demand, underwritten by Russian supply, and when gas was framed as a bridge fuel. In an earlier article in this series, I walked through why that assumption was already far more than suspect at the time and why subsequent events have made it untenable. Even before hydrogen entered the picture, this pipeline represented a major, long lived climate commitment.

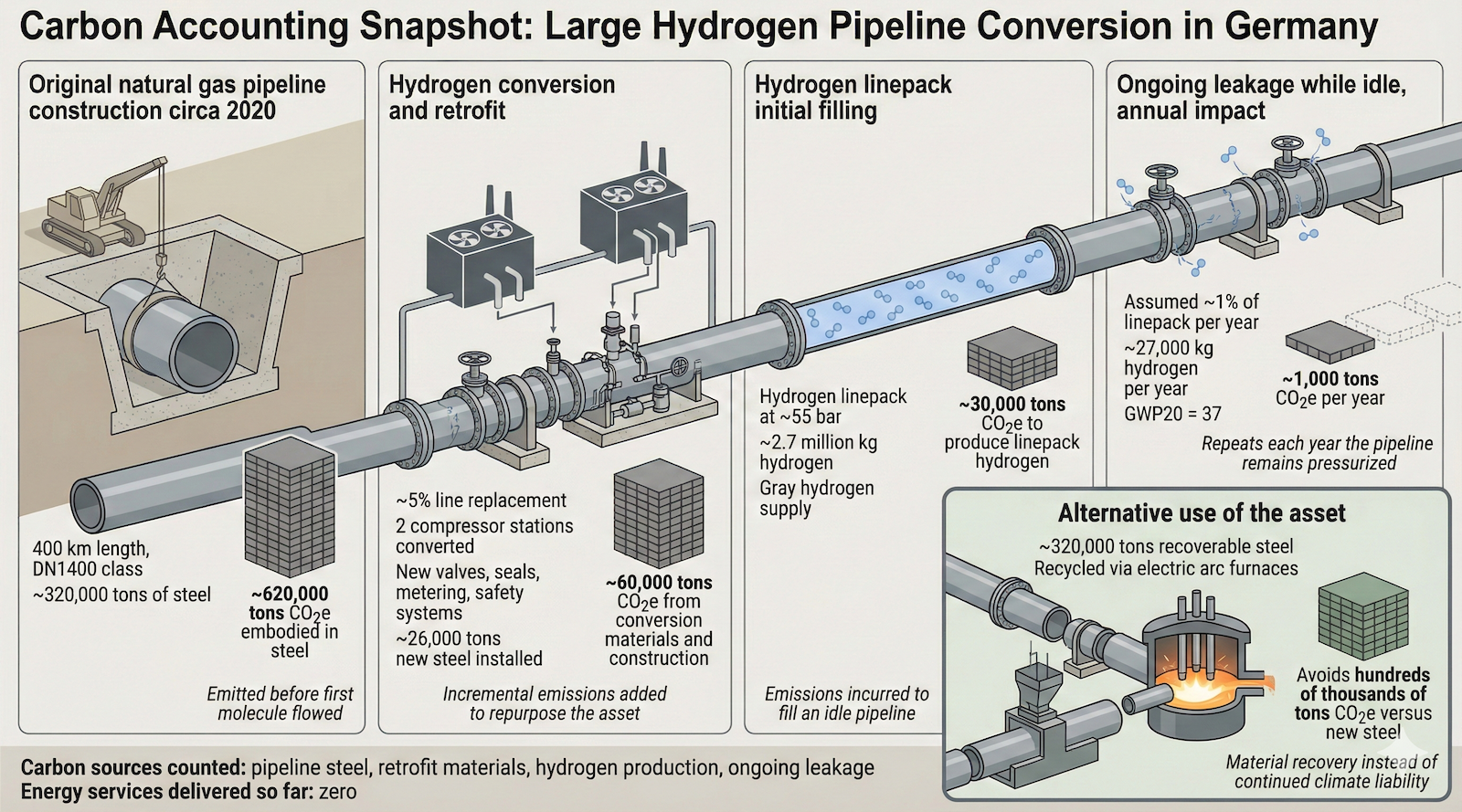

A pipeline of this size is dominated by steel. Using typical German transmission specifications for DN1400 class pipe, with wall thickness around 23 mm, the steel embedded in 400 km of line works out to roughly 320,000 tons. That is not a rounding error. It is about 1% of Germany’s annual apparent steel demand in recent years, committed in a single linear asset whose sole function was to move fossil methane. Steel does not arrive without carbon. Depending on the steelmaking route, producing that much pipe steel would have emitted between roughly 220,000 tons CO2e at the low end, if supplied predominantly from scrap based electric arc furnaces, and around 750,000 tons CO2e at the high end if supplied from blast furnace basic oxygen routes. A central estimate using global average steel intensities lands around 600,000 to 650,000 tons CO2e. That carbon was emitted before the first cubic meter of gas flowed.

That embodied carbon is sunk. It cannot be undone. The only remaining question is whether the asset delivers enough climate value over its lifetime to justify having spent it. When the pipeline carried natural gas, the answer was already doubtful given Germany’s climate targets and the rapid scaling of wind, solar, and electrification. Converting the pipeline to hydrogen does not reset the ledger. It adds new entries on top of an already large balance.

The conversion itself was not trivial. Converting a high pressure gas transmission line to hydrogen service means replacing compressors, seals, valves, metering, regulation, safety systems, and sections of pipe that do not meet hydrogen compatibility or fracture control requirements. For the purpose of this analysis, I assumed a fairly aggressive but plausible scope. About 5% of the line length is replaced with new pipe. Two compressor stations are fully converted or rebuilt for hydrogen service. New metering and regulation stations are installed at major nodes. This is consistent with public descriptions of hydrogen conversion work and with engineering reality. As I noted in the earlier piece, Gascade’s regulated asset base model leads to it maximizing conversion work to maximize capital costs it can accrue ratepayer payments for for decades.

On that basis, the incremental steel installed during conversion is on the order of 26,000 tons. About 16,000 tons of that is replacement linepipe. The remainder is split across large diameter hydrogen rated valves and actuators, pigging facilities and tie ins, compressor station piping and structures, metering and regulation skids, and miscellaneous structural steel. Compressor stations also require substantial concrete foundations and equipment pads, adding several thousand tons CO2e in cement related emissions. Electrical systems, controls, analyzers, and safety instrumentation add further embodied carbon, small in mass but not negligible in climate terms.

When all of that is added up, the incremental embodied emissions of the conversion land in a range of roughly 25,000 to 80,000 tons CO2e, with a central estimate around 60,000 tons CO2e. This is new carbon, emitted in the 2020s, layered on top of the hundreds of thousands of tons already embedded in the original pipeline. In earlier pieces in this series, I argued that infrastructure first hydrogen strategies quietly shift climate risk forward in time. This is one of the mechanisms by which that happens.

The steel and concrete are only part of the picture. Once the pipeline was converted, it was pressurized and filled with hydrogen. At around 55 bar, a 400 km, 1.4 m diameter pipeline holds roughly 2.7 million kg of hydrogen as linepack. That hydrogen did not appear out of nowhere. Germany does not currently have surplus green hydrogen available at this scale. Public statements from operators indicate that conventional industrial hydrogen was used for initial filling.

Gray hydrogen produced from natural gas via steam methane reforming typically carries emissions of around 10 to 12 kg CO2e per kg of hydrogen when upstream gas supply and process energy are included. Filling the linepack with 2.7 million kg of hydrogen therefore implies roughly 27,000 to 32,000 tons CO2e emitted just to put molecules into an idle pipe. That carbon was emitted without delivering any energy services, industrial decarbonization, or avoided fossil fuel combustion.

Once hydrogen is in the pipe, it does not sit there without losses. Even when a pipeline is idle, leakage occurs through valves, seals, instrumentation, and fittings. Hydrogen molecules are small and mobile, and seal degradation over time is a known issue in hydrogen systems. Leakage rates are often discussed as percentages that sound reassuringly small, but percentages applied to large inventories and long time periods accumulate.

A bad but plausible leakage case for an idle transmission segment is around 1% of linepack per year. Applied to 2.7 million kg of hydrogen, that is about 27,000 kg per year, or roughly 74 kg per day. Over a 20 year time horizon, hydrogen has a global warming potential of about 37 times CO2 due to its indirect effects on methane and ozone. At that GWP20, leaking 27,000 kg of hydrogen in a year corresponds to roughly 1,000 tons CO2e per year. That impact repeats every year the pipe remains pressurized and unused. It is not a one time event.

At this point in the accounting, several categories of emissions are clear. Hundreds of thousands of tons CO2e embedded in the original steel. Tens of thousands of tons CO2e added during conversion. Tens of thousands of tons CO2e emitted to produce hydrogen to fill the line. Ongoing annual climate impacts from leakage in the range of a thousand tons CO2e per year. What is missing from the ledger is equally important. There is no delivered energy. There is no displaced fossil fuel use. There is no industrial process that has been decarbonized by this asset so far.

In an earlier article in this series, I compared Germany’s hydrogen backbone concept to China’s industrial hydrogen pipelines. The distinction matters here. China’s pipelines connect existing green hydrogen production to existing hydrogen demand in steel, chemicals, and refining. Molecules flow because there is already a reason for them to do so. The pipeline is sized to demand. Germany’s backbone was sized and built for natural gas on the assumption that building the pipe would create demand, which was likely true for that gas as it was extending use of the energy carrier and industrial feedstock in the economy, but not for hydrogen. Energy systems do not work that way. Without demand, the infrastructure sits, and its climate costs continue to accrue.

There is also a significant opportunity cost embedded in keeping this steel in the ground. Large diameter pipeline steel is high quality material that electric arc furnaces need as feedstock to decarbonize steelmaking itself. Roughly 320,000 tons of pipeline steel, if dismantled and recycled, could displace a meaningful amount of primary steel production. Even using conservative assumptions, recycling that steel through EAFs would avoid hundreds of thousands of tons of CO2e compared to producing the same amount of new steel from iron ore. Germany and Europe face chronic shortages of suitable scrap as they try to shift steelmaking away from blast furnaces. Leaving high quality steel locked into an idle pipeline is not a neutral choice. It delays recycling and prolongs higher emissions elsewhere in the system. I assessed Europe’s green steel industrial future in another piece, pointing out the high likelihood of green iron being manufactured off the continent and shipped as a bulk commodity instead of iron ore, and scrap steel increasing.

Keeping the pipeline in place is often framed as prudence, as waiting for hydrogen demand to arrive. From a climate accounting perspective, waiting is an active decision. It means accepting ongoing leakage. It means deferring scrap recovery. It means accepting that additional hydrogen will be produced and vented or leaked during maintenance, depressurization, and recommissioning cycles. The alternative, decommissioning and recycling, has a one time emissions cost but stops the ongoing bleed and recovers material value.

This does not require assuming bad faith or incompetence on the part of planners. It follows from how infrastructure led decarbonization strategies behave when demand assumptions fail. Steel is real. Concrete is real. Compressors and valves are real. Molecule based demand projections are not. When those projections do not materialize, the physical assets remain, along with their climate liabilities.

The uncomfortable conclusion is that, from a climate perspective, this pipeline is currently more valuable as scrap than as a hydrogen asset. Recycling the steel supports decarbonization of another hard to abate sector. Leaving it pressurized extends a chain of emissions without delivering benefits. Admitting that earlier than planned is not a failure of climate ambition. It is an example of taking climate accounting seriously enough to change course when the numbers no longer add up.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy