Addressing the Scale-Up Challenge for Clean Energy Process Technologies

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

By Dhruv Soni, Senior Technical Program Manager at Tesla Battery Minerals and Metals, CELI 2025 Fellow

In the clean energy boom of the 2020s, the United States has continued to lead the world in early-stage innovation, especially across next-generation chemical process industries such as carbon capture, hydrogen and ammonia, sustainable fuels, long-duration energy storage, battery materials, and recycling. Similar to the 1970s and 2000s, the U.S. is still inventing technologies from “zero-to-one” while China is scaling them from “one-to-one-hundred.” This strategy worked in the past, but today’s pressures make it unsustainable.

Environmental disasters are intensifying and disproportionately hurting low-income communities and developing nations, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and World Bank. Meanwhile, many major resource-producing regions continue to operate under lax environmental and ethical standards. At the same time, the world is entering a “New Joule Order” marked by geopolitical realignment and energy supply diversification. The problem statement is clear: we need effective clean energy solutions fast.

Although it once was, scientific innovation is no longer the bottleneck to these solutions. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that we can meet 2030 emissions targets with technologies available today and 2050 emissions targets with technologies currently in the demonstration or prototype phase. As Breakthrough Energy argues, the United States must deploy technologies at scale and rebuild domestic industrial capacity. And although process scale-up will be difficult without the right infrastructure and expertise, the convergence of artificial intelligence, favorable policy environments, and renewed industrial focus presents an opportunity for the U.S. to close the deployment gap and become the world’s first “zero-to-one-hundred” clean energy leader.

The Unique Challenge of Clean Energy Scale-Up

In chemical engineering, scale-up refers to the systematic increase in process throughput from lab or pilot scale (up to 1000-kg-per-day) to commercial scale (over 100,000-kg-per-day) to achieve cost efficiencies, project returns, and greater impacts. This transition is inherently difficult because the fundamental physical and chemical behaviors generally do not scale linearly. For example, a 2-liter lab crystallizer cannot easily predict the supersaturation gradients, scaling tendencies, and non-uniform mixing that may emerge in a 20,000-liter unit. Larger systems also require higher up-front investments, and both the engineering and financial risks are amplified when developing first-of-a-kind (FOAK) process technologies.

Legacy industries such as petrochemicals have historically solved this problem through decades of iteration and data collection. Unfortunately, the clean energy sector cannot afford to spend millions of dollars and several decades maturing each new technology. The climate clock is ticking, and we cannot rely on traditional approaches to meet the urgency of intensifying natural disasters.

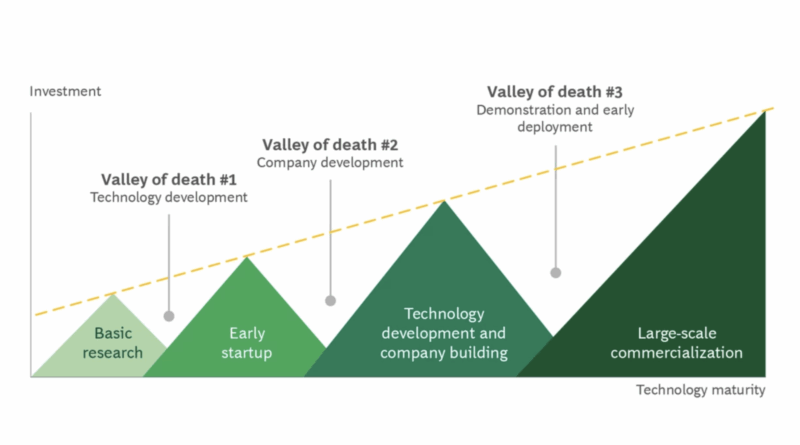

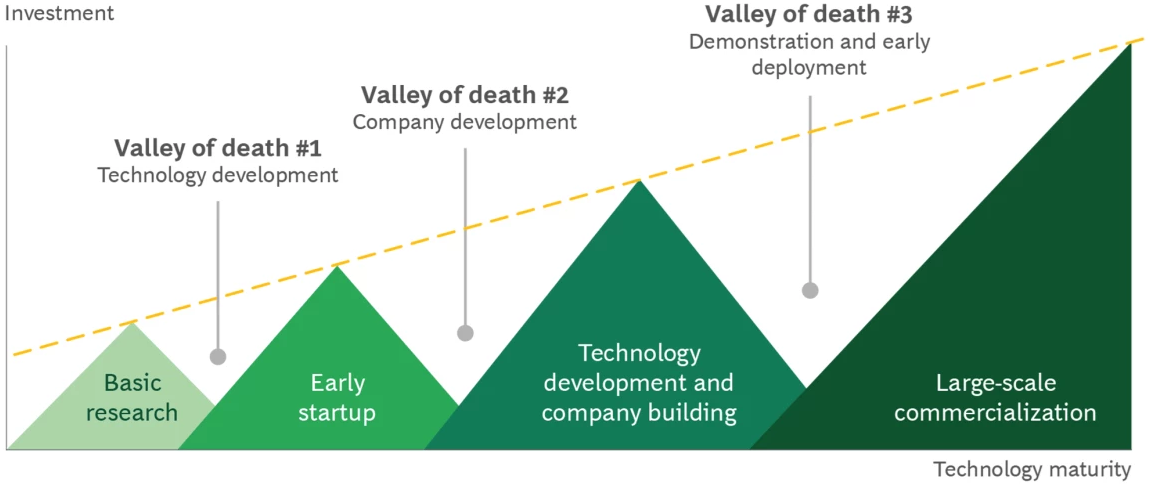

Moreover, process scale-up does not occur in isolation — it is tightly coupled with business functions such as fundraising, siting and permitting, equipment procurement, and workforce development. These activities introduce distinct failure modes, which Jacob Miller categorizes as (a) cost growth, (b) process uncertainty, or (c) project uncertainty. The “valley of death” framework adapted by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) illustrates how these technical and financial risks intersect during commercialization.

In summary, process scale-up is difficult in any sector but uniquely complex for clean energy technologies. Recent outcomes underscore this: according to Jacob Miller, 81% of U.S. venture-backed clean energy startups that received seed funding in 2010 either failed or exited at low valuations. Nevertheless, we can mitigate cost, process, and project risks by optimizing process design and modernizing project execution strategies — ultimately increasing the likelihood of successful scale-up.

Optimizing Process Design

The first clear lever to facilitate scale-up of clean energy technology is process design. As projects move from the lab into the field, we need to maintain an emphasis on modularization. It is generally much lower risk to build ten 20,000-ton-per-year demo-scale modules in parallel than a single 200,000-ton-per-year commercial FOAK plant. Modularization also brings several downstream benefits by simplifying siting, enabling off-site fabrication, consolidating spare parts, and shortening learning cycles. Hydrogen electrolyzer skids and skidded direct-air-capture units have shown the power of “numbering up” instead of “sizing up” to facilitate project delivery and improve process confidence.

We should also design processes to integrate with existing infrastructure, from local utilities to global supply chains. As Gabriele Centi notes, integrating new technologies into current value chains lowers the upfront costs and accelerates adoption. For example, ammonia fuel startups are targeting to use the same port-and-storage infrastructure that already handles ammonia fertilizer. This accelerates adoption by decreasing integration costs, enabling familiar pricing structures, and tapping into an existing talent pool.

Finally, we need a renewed emphasis on digital simulation through engineering and design. Maintaining a digital twin with a live mass-and-energy-balance allows teams to evaluate how design changes affect energy consumption, throughput, and chemical performance. When linked to the project technoeconomic model, it can assess financial sensitivities and forecasted returns. With enough pilot or demo data, the digital twin can guide startup decisions and shorten commissioning timelines. While small improvements are being made, this remains an area ready for disruption. Oil and gas, chemicals, and mining have relied on conventional modeling for decades, but recent advances in artificial intelligence can enable these tools to serve as proactive engines for design optimization, cost modeling, and active process control.

Modernizing Project Execution

Perhaps the largest lever to improve clean energy scale-up is project execution. The legacy model – outsourcing the full engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) scope to a single firm – works well for mature industries but is too rigid for new technologies. Clean energy FOAK projects need full control, tight alignment, and quick feedback between process development and detailed engineering. And while EPCs excel at documentation and project controls – the associated overhead often outweighs the value for early-stage developers. More critically, outsourcing turnkey EPC scope shifts the incentives from project delivery to contract exploitation, leading to cost overruns and schedule delays.

Alternatively, companies should build in-house project management and discipline engineering teams to control their own outcomes. For example, an internal piping engineering team can quickly adjust specifications and routing based on corrosion and erosion data shared by the technology team. Site development, modularization, and other civil-structural considerations can be incorporated with greater accuracy at the feasibility stage. Most importantly, in-house engineering functions allow parallel and iterative workstreams, enabling a “vertical” schedule rather than a slow, linear one. Then, EPCs can be leveraged for specialty support on tighter scopes such as environmental permitting, process safety reviews, and construction sequencing. This strategy enables faster decision-making and greater technical accuracy which ultimately decrease cost, schedule, and technology risk in aggregate.

Finally, the digital backbone of project delivery also needs to be modernized. Data continuity across design phases remains weak compared to discrete manufacturing industries, where every variable is tracked closely. Design metadata often does not transfer intelligently across phases, creating rework and delays – such as manually regenerating material takeoffs (MTOs). File formats – such as equipment models or piping isometrics – are rarely interchangeable, causing constant conversions and information loss. And while live design collaboration tools are improving, they still lag behind other software-first sectors. Strong project execution must be paired with fit-for-purpose digital tools capable of managing the full design-to-construction project lifecycle in order to facilitate project success.

Conclusion

Clean energy scale-up is a technically demanding and capital intensive challenge that is heavily shaped by shifting markets, policy environments, and geopolitical pressures. Beyond the strategies discussed here, there is still work to do in permitting reform, government support, workforce development, late-stage funding, and energy justice. Nevertheless, process design and project execution are two levers that cleantech developers can control right now to achieve success in commercialization. Strengthening these foundations is what will enable the United States to move beyond invention into deployment and become a true “zero-to-one-hundred” clean energy leader.

About the Author

Dhruv Soni is a chemical engineer currently working in Tesla’s Battery Minerals and Metals organization, helping scale domestic production of raw materials necessary for cell manufacturing. He played a key role in the engineering design, equipment procurement, and project management of Tesla’s lithium refinery in Corpus Christi, Texas. He is now working on early-stage project development for other battery materials while supporting the construction and commissioning of the lithium refinery. At nameplate, the lithium project will be the largest source of domestic battery-grade lithium hydroxide, which will be produced using a first-of-a-kind chemical process technology. Outside of work, Dhruv is a member of the 2025 fellowship cohort of the Clean Energy Leadership Institute (CELI) and is passionate about using his chemical engineering education and capital projects background to accelerate the world’s transition to clean energy.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy