China Built A Supercritical CO₂ Generator. That Doesn’t Mean It Will Last.

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

China recently placed a supercritical carbon dioxide power generator into commercial operation, and the announcement was widely framed as a technological breakthrough. The system, referred to as Chaotan One, is installed at a steel plant in Guizhou province in mountainous southwest China and is designed to recover industrial waste heat and convert it into electricity. Each unit is reported to be rated at roughly 15 MW, with public statements describing configurations totaling around 30 MW. Claimed efficiency improvements range from 20% to more than 30% higher heat to power conversion compared with conventional steam based waste heat recovery systems. These are big numbers, typical of claims for this type of generator, and they deserve serious attention.

China doing something first, however, has never been a reliable indicator that the thing will prove durable, economic, or widely replicable. China is large enough to try almost everything. It routinely builds first of a kind systems precisely because it can afford to learn by doing, discarding what does not work and scaling what does. This approach is often described inside China as crossing the river by feeling for stones. It produces valuable learning, but it also produces many dead ends. The question raised by the supercritical CO₂ deployment is not whether China is capable of building it, but whether the technology is likely to hold up under real operating conditions for long enough to justify broad adoption.

A more skeptical reading is warranted because Western advocates of specific technologies routinely point to China’s limited deployments as evidence that their preferred technologies are viable, when the scale of those deployments actually argues the opposite. China has built a single small modular reactor and a single experimental molten salt reactor, not fleets of them, despite having the capital, supply chains, and regulatory capacity to do so if they made economic sense.

Likewise, China’s hydrogen transportation efforts have faded as battery electric vehicles have achieved overwhelming commercial success across passenger cars, buses, trucks, and two wheelers. This matters because China does not hesitate to scale technologies that work. When something proves commercially robust, it appears by the tens or hundreds of thousands, not as one off demonstrations. Pointing to a handful of reactors or hydrogen pilots in a system that deploys millions of BEVs and hundreds of gigawatts of wind and solar is not evidence of future viability. It is evidence that these alternatives have been tested and found wanting, or that some experiments are being run around the edges. If small modular reactors or hydrogen transportation actually worked at scale and cost, China would already be building many more of them, and the fact that it is not should be taken seriously rather than pointing to very small numbers of trials compared to China’s very large denominators.

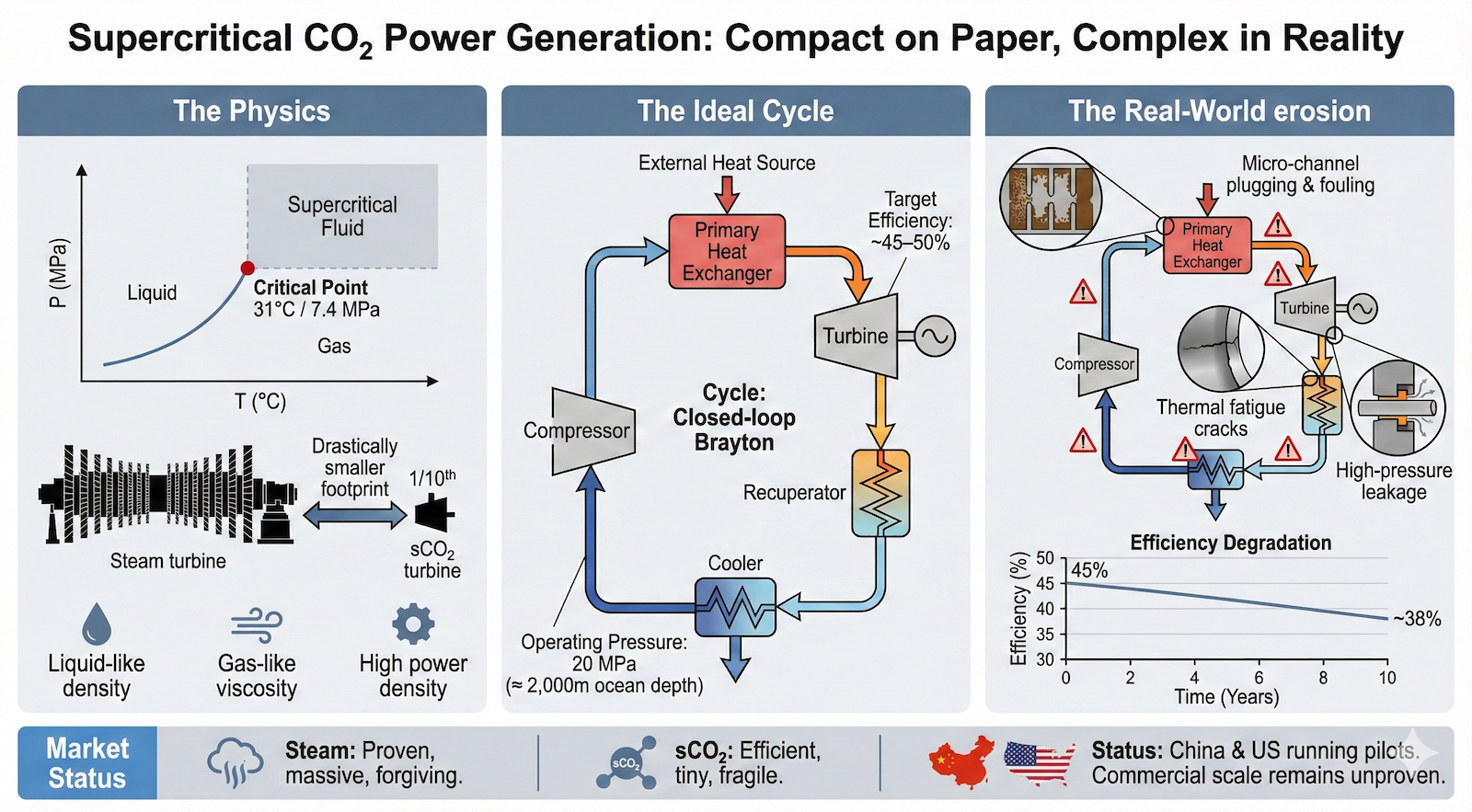

Supercritical CO₂ power systems are a form of thermal generation. They take heat from some source and convert part of that heat into mechanical work, which then drives an electrical generator. This is the same basic objective as every coal plant, gas plant, nuclear plant, or waste heat recovery system built over the past century. The difference lies in the working fluid and the thermodynamic cycle used to extract work from heat.

Carbon dioxide becomes supercritical above roughly 31° Celsius (about 88° Fahrenheit for American readers) and 73 atmospheres of pressure, which is like being 740 meters (almost half a mile) under the surface of the ocean. In that state it is neither a normal gas nor a normal liquid. It has a density closer to a liquid while flowing like a gas. Engineers find this attractive because in theory it allows much smaller turbomachinery for a given power level. High density means high mass flow in a compact volume. This is why supercritical CO₂ cycle proposals often advertise small turbines, compact heat exchangers, and reduced physical footprint, part of recurring hype cycles for the technology. That it uses homeopathic amounts of carbon dioxide and can also take advantage of carbon capture and utilization hype cycles is a multiplier effect for its recurrence, but once again should induce skepticism, not acceptance of claims.

The thermodynamic cycle used in these systems is typically a Brayton cycle. In simple terms, a Brayton cycle compresses a fluid, heats it, expands it through a turbine to produce work, and then cools it before repeating the process. Jet engines and gas turbines operate on Brayton cycles using air or combustion gases. Traditional waste heat recovery systems usually use a Rankine cycle instead, boiling water into steam, expanding it through a turbine, condensing it, and pumping it back to pressure.

Brayton cycles can achieve high efficiency when the working fluid properties are favorable and when losses are tightly controlled. Supercritical CO₂ offers favorable properties on paper. Near the critical point, small temperature changes lead to large density changes, reducing compression work and improving cycle efficiency. This is where many of the efficiency claims originate. In practice, these same properties also make the system sensitive to small deviations, contamination, and surface degradation.

The Chinese installation is an indirect heated closed loop system. Heat from the steel plant is transferred through heat exchangers into the CO₂ loop, which then drives a turbine and generator connected to the grid. Public reporting states that the system operates at pressures around 200 atmospheres of pressure, like being two kilometers or one and a quarter miles under water, and temperatures in the range of several hundred degrees Celsius. Claims of efficiency improvements often cite numbers like 45% cycle efficiency compared with 35% for comparable steam based waste heat systems, or electricity output gains of 20% to 30% from the same thermal input. These would attractive improvements if they could be sustained.

What is notably absent from publicly available information is detailed disclosure of materials, operating margins, impurity controls, and maintenance assumptions. This is not unusual for early commercial deployments in China. It does mean that external observers cannot independently assess long term durability claims.

The United States has taken a different path with supercritical CO₂ generation. The most prominent effort is the DOE backed Supercritical Transformational Electric Power (STEP) facility in Texas, part of decades of effort, research and investment from the organization. That installation is rated at roughly 10 MW electric. It reached initial power generation in 2024 after several years of construction and commissioning. Its stated purpose is not commercial operation but component validation, system behavior characterization, and risk reduction. The U.S. effort is accompanied by extensive laboratory work at national labs, including long duration corrosion tests, alloy qualification, and impurity sensitivity studies.

Supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycles are not a new idea. Variants have been proposed repeatedly since the mid twentieth century, with the DOE often providing the funding. The recurring obstacle has never been thermodynamics. The obstacle has always been materials and durability at the combination of temperature, pressure, chemistry, and cycling required for real power systems. This is such a recurring technology that I explicitly call it out in my red flags checklist.

Is it old tech claiming to be new tech? A lot of things are recycled ideas. Every decade or so someone reinvents shrouded and ducted wind turbines that don’t work better than existing wind turbines. The wind turbine blades on a clothesline mentioned above has been reinvented twice. Ground effect airplanes make a comeback every ten to fifteen years. Blimps get headlines about that often. The iron air redox reaction is incredibly well understood and has been since it was first tried for energy storage in the 1950s. Supercritical CO₂ turbines have been attempted since 1946 without success.

With the latest Chinese effort getting a lot of attention and driving another mini-hype cycle, I decided that it was time to get even nerdier about the technology. I had included it in my lengthy assessment of supercritical CO₂ hype a couple of years ago, but hadn’t gone deeper into the problems. The most important thing to understand about failure in these systems is that it does not come from a single problem. It comes from overlapping degradation mechanisms that interact and amplify one another.

Heat exchangers sit at the center of this risk stack. Supercritical CO₂ systems rely on printed circuit heat exchangers with extremely small channels, often measured in millimeters or less. These exchangers must withstand pressures of 200 atmospheres or more while operating at high temperature. Carbon dioxide at supercritical conditions readily transports carbon into steels and some stainless alloys. This carburization leads to carbide formation, embrittlement, and changes in surface condition. In microchannels, small changes in surface roughness or cross section can produce large increases in pressure drop. Pressure drop directly reduces cycle efficiency by increasing compression work.

The challenge of keeping seals intact in supercritical CO₂ power systems is closely analogous to the challenge of sealing high pressure hydrogen systems, even though the underlying physics differs. In both cases, the systems rely on containing a small, highly mobile molecule at very high pressure, often at elevated temperature, across rotating shafts, flanges, and joints that experience thermal and mechanical cycling. Seal degradation is rarely a sudden failure. It is usually gradual, difficult to detect directly, and first shows up as efficiency loss rather than as a clear fault. In hydrogen systems, leakage reduces delivered energy and increases compression losses. In supercritical CO₂ systems, leakage alters working fluid inventory and shifts compressors away from their optimal operating point, increasing parasitic loads and reducing net output. In both cases, operators compensate through control adjustments, masking the underlying degradation.

The dominant failure mechanisms differ, but the operational outcome converges. Hydrogen’s extremely small molecule and chemical reactivity drive diffusion, permeation, and embrittlement in many materials, shortening seal and component life. In hydrogen refueling stations, seal failure is the dominant failure condition, accounting for 50% of the very large number of very lengthy service failures in California’s hydrogen refueling stations in 2021 per DOE reports, before they stopped reporting publicly on the ongoing failures.

Supercritical CO₂ does not embrittle metals in the same way, but its liquid like density combined with gas like mobility makes it unforgiving of small imperfections, while thermal cycling, high pressure, and impurity driven corrosion accelerate mechanical wear at seal interfaces. The result in both systems is the same pattern: leakage rates rise over time, maintenance effort increases, and headline performance claims quietly erode. Experience with hydrogen suggests that expecting seals to remain effectively perfect over many years of continuous high pressure operation is absurdly optimistic, and there is little reason to assume supercritical CO₂ systems will escape a similar long term reality.

Over a two to five year operating period, the probability of measurable heat exchanger performance degradation is not trivial. For an installation like the Chinese steel plant system, operating continuously on industrial waste heat, a reasonable probability range for noticeable degradation is 40% to 70%. For U.S. pilot systems with shorter duty cycles and more conservative materials choices, a range of 25% to 50% is more plausible. These are not catastrophic failures. They are slow losses that erode headline efficiency claims.

Impurity driven localized corrosion is a separate and serious risk. Supercritical CO₂ itself is relatively benign when dry and pure. Small amounts of water, oxygen, sulfur compounds, nitrogen oxides, or chlorides change the chemistry dramatically. Like hydrogen in energy systems, supercritical CO₂ requires rather absurd levels of gas purity. Localized pitting and crevice corrosion can occur at joints, diffusion bonded interfaces, and stagnation points. Waste heat from steel production almost inevitably carries contaminants unless aggressively scrubbed and dried. Localized corrosion tends to manifest as leaks or sudden outages rather than gradual derating. Over a multi year window, the probability of this type of failure is plausibly 30% to 60% for an industrial Chinese deployment and 15% to 35% for U.S. test facilities with tighter purity control.

Diffusion bonding itself introduces another failure pathway. Diffusion bonding is a manufacturing process used to join metal components without melting them, and it is central to the compact heat exchangers required by supercritical CO₂ power systems. In diffusion bonding, precisely machined metal plates are stacked, heated to a high temperature below their melting point, and pressed together under high pressure in a vacuum or inert environment for many hours. Atoms migrate across the contacting surfaces, gradually eliminating the interface and creating a joint that behaves like a single piece of metal. This makes it possible to fabricate printed circuit heat exchangers with thousands of very small internal flow channels that can withstand pressures on the order of 200 atmospheres of pressure while remaining compact.

The economic implications are significant. These heat exchangers are costly because they rely on high grade alloys, precision etching, long bonding cycles, and specialized equipment. Once degradation or leakage begins at the bonded interfaces, repair is not practical, and the entire exchanger usually has to be replaced. Exchanger lifetime therefore becomes a critical driver of system economics, and shorter than expected service life can quickly erase the efficiency gains that motivate supercritical CO₂ designs in the first place. Over two to five years, the probability of bond related leakage or structural degradation is reasonably estimated at 35% to 65% for early commercial systems and 25% to 45% for test installations.

Turbomachinery degradation is more subtle but unavoidable. Brayton cycle efficiency depends on maintaining smooth aerodynamic surfaces and stable flow regimes. Supercritical CO₂ near its critical point is highly sensitive to small changes in density and viscosity. Minor surface roughening from corrosion or erosion can alter how smoothly the working fluid flows through a compressor. That increases internal losses, raises the energy required to achieve the same pressure increase, and reduces the amount of useful power the overall cycle can deliver. This does not usually trigger alarms. It shows up as declining output for the same thermal input. A 20% to 40% probability of noticeable efficiency loss from this mechanism over two to five years is realistic for both Chinese and U.S. systems.

Seal performance and inventory control add another layer. Supercritical CO₂ systems rely on maintaining a precise mass of working fluid to keep compressors operating in their optimal range. Small leaks are hard to detect and harder to eliminate at high pressure. Seal materials face extreme conditions. Inventory drift increases compression work and reduces net output. This is a quiet failure mode that operators compensate for by retuning controls. Over a multi year period, the probability of meaningful efficiency loss from seal and inventory issues likely sits between 40% and 70% for early systems, with somewhat lower values for heavily instrumented pilots.

For the Chinese installation specifically, hot side fouling from the industrial heat source may dominate all other degradation mechanisms in the early years. Steel plant exhaust streams contain particulates, metal oxides, and sulfur compounds. Fouling reduces effective heat transfer before CO₂ chemistry even becomes the limiting factor. This pushes turbine inlet temperatures down and reduces net power output. The probability of fouling driven performance loss in such a setting over two to five years is easily 60% to 85%.

What ties all of these mechanisms together is that they rarely present as dramatic failures. Operators adjust control strategies. Maintenance intervals creep shorter. Net output slowly declines. Efficiency claims made at commissioning quietly soften. The expected economic benefits degrade or are eliminated. The system still works. It just does not work as well as advertised.

This does not mean the Chinese or U.S. efforts are misguided. It does mean that early efficiency claims should be treated as provisional. A system that starts at 15 MW and delivers 13 MW after several years with rising maintenance costs is not a breakthrough. It is an expensive way to recover waste heat compared with mature steam based alternatives that already operate for decades with predictable degradation.

Looking forward, I don’t see supercritical CO₂ Brayton cycles becoming a significant share of electricity generation. They may find niche roles in specialized waste heat recovery or tightly controlled industrial environments. They do not look poised to displace conventional thermal systems at scale. If both the Chinese and U.S. installations run for five years without significant reductions in performance and without high maintenance costs, I will be surprised. In that case, it would be worth revisiting this assessment and potentially changing my mind. Until then, this looks like an interesting experiment rather than a foundation for the future power system.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy