America’s Drone Ban Hands Productivity Gains To The Rest Of The World

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

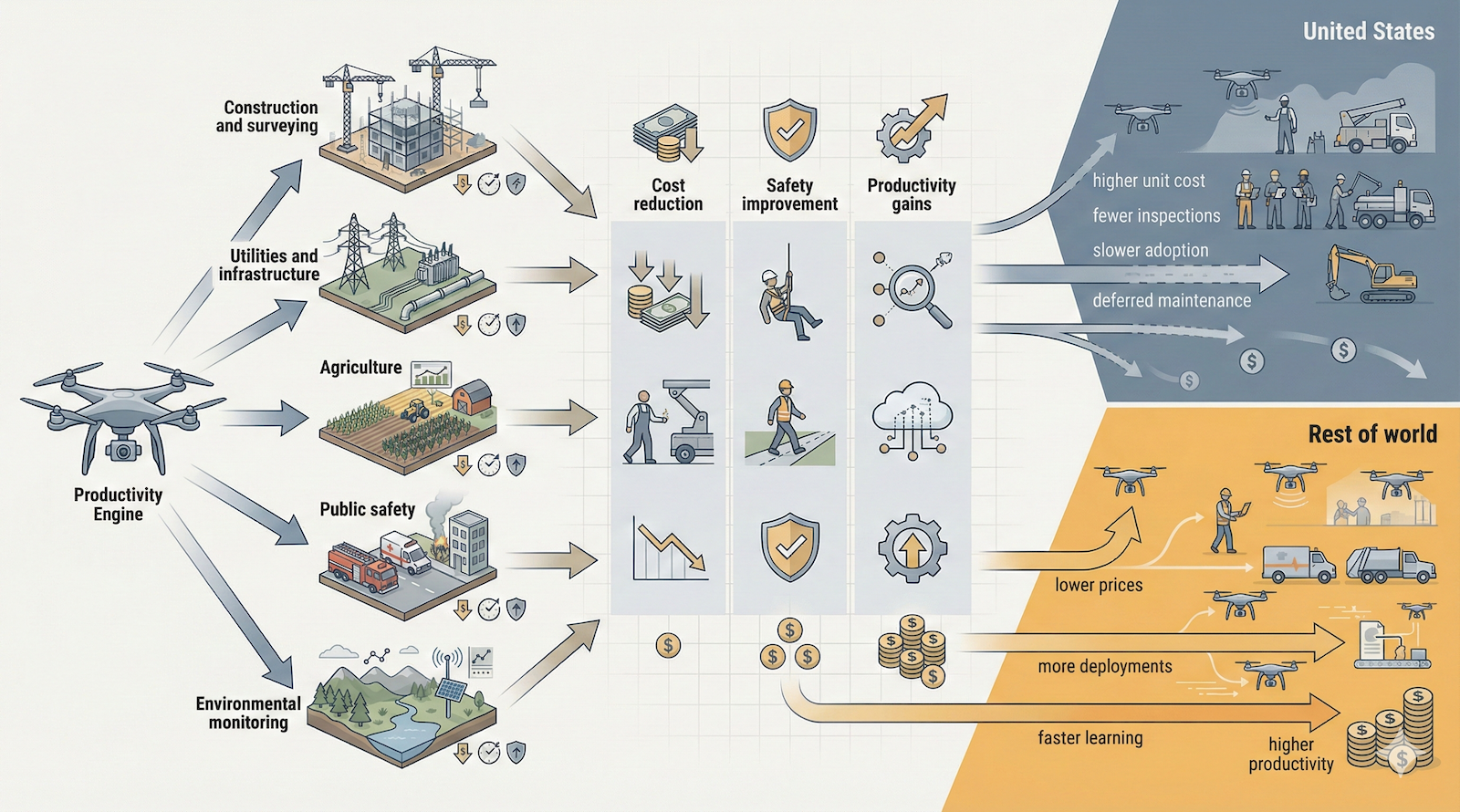

The recent US decision to block new certifications for Chinese drones is being framed as a narrow national security measure. In practice it is a broad economic choice with long shadows. The policy does not ground existing drones or seize equipment. It works through certification attrition, cutting off the ability of the dominant suppliers to refresh hardware and keep products current. That sounds technical and contained. It is not. This approach quietly reshapes access to one of the most important general purpose productivity tools now embedded across construction, utilities, agriculture, public safety, and infrastructure. It’s going to cost the US economy billions annually and hand those gains to the rest of the world.

What is actually being restricted matters. Drones already approved for sale and operation remain legal. Fleets in the field keep flying. Warehoused inventory keeps moving. The change is that new models and revised hardware configurations will not receive approval. In fast moving electronics markets, that distinction is decisive. Certification is tied to exact hardware configurations. Radios, antennas, chips, power management components, and layouts drift as suppliers change and parts go end of life. When that drift can no longer be recertified, products stop evolving and then stop shipping. This is not a ban on use. It is a ban on keeping up.

That matters because DJI sits at the center of the civilian drone ecosystem. Its dominance is not symbolic. It reflects years of integration across airframes, cameras, radios, batteries, flight control, and software. The result is a price and capability envelope that competitors have not matched at scale. In most civilian categories, DJI drones are less expensive for a given level of capability, available in volume, and supported by mature software and service networks. There are niches where others outperform it. Those niches tend to come with higher prices, longer lead times, and narrower mission profiles. For the median user across millions of flights, DJI set the baseline. That’s true globally, and that’s true in the USA, where DJI owns 70% to 80% of the market across virtually all civilian segments.

The impact of the US policy will not be immediate. For the first six months, little changes on the surface. Inventory buffers absorb demand. Manufacturers prioritize frozen designs. Operators continue business as usual. Between six and twelve months, stress begins to show. Components used in certified models go end of life. Silent revisions become harder to avoid. Certain configurations disappear from catalogs. Lead times stretch. Between twelve and twenty four months, the effects become hard to ignore. Models age. Replacement cycles break. Import risk rises. This is the same pattern seen with telecom equipment and surveillance hardware. Nothing dramatic happens at first. Then the ecosystem hollows out.

Replacement options exist, but they do not offer parity across price, capability, and availability. In defense and some government niches, domestic suppliers can meet requirements, at higher cost and lower volume. In enterprise inspection and public safety, some alternatives provide strong autonomy features, again at higher prices and with supply constraints. In consumer and prosumer categories, there is no realistic replacement at scale. The shift is from consumer electronics economics to aerospace economics. That means fewer units deployed per dollar, slower delivery, and narrower use.

The largest economic effect is not lost drone sales. It is lost enabled value. Drones displace labor, reduce downtime, and lower risk. They allow inspections to happen more often, earlier, and in more places. When unit costs rise and availability falls, operators respond by flying less. Inspections are deferred. Coverage shrinks. Maintenance becomes reactive again. The loss shows up as higher operating costs across construction, utilities, and infrastructure, not as a line item in drone industry revenue.

Safety implications follow from that shift. Drones replaced people working at height, entering confined spaces, standing roadside, and flying low altitude inspection missions. When drones become scarcer or more expensive, some of that work returns to humans. This does not guarantee accidents. It increases exposure to known risks. Over large workforces and long timeframes, that matters.

Energy and emissions effects follow as well. Drones displaced helicopters and small aircraft for inspection and survey work. Helicopters burn Jet A at high rates. Fixed wing piston aircraft burn avgas. Ground inspections add vehicle miles. Even partial reversion erases a meaningful share of the emissions savings drones delivered. These effects are upstream and diffuse. They will not show up as a single spike in fuel data. They will show up as missed reductions.

Agriculture illustrates the dynamic clearly, as I noted recently. In the US, drone spraying and seeding were not dominant, but they were growing fast. They displaced marginal tractor passes that burn diesel without moving much product. They enabled spot treatments, late season applications, and work in wet conditions. That reduced diesel use per acre and improved yields. The value was in trajectory, not immediate transformation. Slowing access to affordable agricultural drones slows that learning curve. The US already lagged China — and many other countries — in adoption scale. This policy widens the gap.

Several independent assessments put real dollar bounds around that enabled value. Industry market sizing places direct US drone sales in the $6 to $8 billion per year range, but that is not where most of the economic impact sits. McKinsey has estimated that commercial drone use contributes roughly $31 to $46 billion per year to US GDP through productivity gains in inspection, surveying, logistics, and infrastructure operations. AUVSI’s long-running airspace integration studies projected more than $80 billion in cumulative economic impact in the mid-2020s as drones are routinely embedded in industrial workflows. PwC’s analysis of drone-powered business services identified tens of billions of dollars of annual value tied specifically to infrastructure inspection, construction, agriculture, and public safety, with North America representing a large share of that opportunity. Losing even 10% to 20% of that enabled activity because drones become scarcer, more expensive, or slower to deploy implies billions of dollars per year in foregone productivity, higher operating costs, and deferred maintenance across the US economy, even though the drone sales market itself remains comparatively small.

Looking globally, the pattern is familiar. When the US restricted imports of Chinese solar panels, batteries, and grid equipment, global manufacturing did not slow. Supply flowed elsewhere. Prices fell outside the US. Deployment accelerated, for example in Pakistan where 17 GW of cheap solar panels were snapped up and deployed in 2024. Learning curves steepened. The US paid higher costs and moved more slowly. Drones fit the same pattern. Manufacturing capacity remains. Innovation continues. The benefits accrue to markets that accept the supply. Once again the USA’s trade policies are going to help the world to leapfrog past it.

This is not about China winning at the expense of the US in a zero sum sense. It is about relative productivity. Countries in Europe, Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa will deploy more drones per dollar. They will inspect more assets, farm more efficiently, and build service ecosystems faster. China and DJI will see limited impact because global demand absorbs output. The US absorbs the cost of opting out.

At the strategic level, the conclusion is not ambiguous. This is the US choosing a higher cost, slower learning equilibrium for a general purpose productivity tool. The frankly dubious security rationale does not remove the economic consequences. It shifts them onto construction timelines, utility reliability, agricultural efficiency, safety outcomes, fuel use, and emissions. The rest of the world captures the gains the US forgoes.

This is not a case of protecting a domestic industry that is ready to scale. Domestic drone manufacturers are tiny niche players. It is a case of constraining an enabling technology without a replacement that matches its economics. The result is not resilience. It is self imposed friction. Over time, that friction compounds. The US loses ground while others move ahead, not because they are smarter or more strategic, but because they kept access to the tools that make work cheaper, safer, and more productive. As I noted in the aftermath of the election in 2024, the world is moving on without the USA as it declines.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy