Big Loads, Small Loads, & A Changing Grid: A Better Path for Scope 2 Accounting?

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

An advocacy piece published by WattTime and REsurety was brought to my attention because it reflects the tension building around the proposed revisions to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol’s Scope 2 accounting rules. These rules are not American regulations. They are global and voluntary, governed by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. Despite their voluntary status, they are treated as the backbone of corporate emissions reporting across most multinational sectors. When something shifts inside the GHG Protocol, entire markets respond. That makes debates about annual matching, hourly matching, locality criteria, and corporate renewable procurement more than abstract methodological arguments. These debates shape how companies report progress, how investors judge risk, and how energy systems evolve.

The significance of the GHG Protocol comes from the scale of its adoption rather than any legal authority. It is the accounting foundation used by the Fortune 500, by most major multinationals, by global financial institutions, and by the major ESG reporting frameworks. CDP requires disclosures aligned with it, and SBTi builds its target setting rules on top of it. Even regulators often mirror its structure because it has become the default language of corporate climate reporting. This reach gives the GHG Protocol an influence that resembles regulation even though it is voluntary. When its rules change, corporate energy procurement, emissions claims, and investment decisions change with them. That scale of adoption is why the current Scope 2 debate matters and why the details of temporal and locational matching will shape the next decade of corporate decarbonization.

The WattTime and REsurety advocacy piece argues strongly against stricter temporal and regional requirements in Scope 2 accounting. They assert that hourly matching rules will make renewable procurement difficult and expensive for many buyers. They warn that geographic restrictions will shut down procurement in parts of the world where avoided emissions are highest. They argue that the voluntary market could shrink at the moment when the world needs it to expand. These concerns deserve examination. They speak to real anxieties among corporate buyers that have relied on flexible procurement structures for ten years.

At the same time the arguments serve the strategic and financial interests of the two firms. Their respected and influential analytics, software, and products support avoided emissions modeling across wide geographies. Stricter temporal and locational rules would reduce the scope of these models. Even so their advocacy is not cynical. Both firms have pushed to align procurement with grid impacts. Both argue that global avoided emissions can deliver more climate benefit than narrow accounting rules. Their sincerity does not erase the fact that the GHG Protocol is wrestling with a larger question. What does it mean for a company to claim clean electricity if the electricity it uses is not necessarily clean in the hours or places where consumption occurs.

WattTime began as a research project within the Rocky Mountain Institute before becoming an independent nonprofit software and analytics organization focused on tracking real time marginal emissions and helping companies shift consumption to cleaner hours on the grid. Its work popularized the idea of emissionality, the practice of selecting renewable projects based on modeled avoided emissions rather than proximity or matching requirements.

REsurety emerged from the early corporate PPA market as a for profit risk analytics firm that built probabilistic tools for valuing renewable energy contracts and later expanded into locational marginal emissions data. Both firms built their reputations by bringing more rigorous, data driven methods to corporate clean energy procurement at a time when the voluntary market was still maturing, and that history shapes their current advocacy for procurement models that preserve global flexibility and rely heavily on modeled grid impacts.

I had a minor interaction with REsurety when they were introducing their virtual PPAs and have deeply assessed RMI’s challenging positions on hydrogen and CCS, recommending a strategic realignment that they appear to have mostly ignored. I’m likely to return to my RMI assessment now that an offshoot is making arguments I can’t agree with in their current form, and RMI itself is making waves with potential overstatements on CCS.

The question of clean energy is easier to navigate when we step back and look at the core principles that underpin credible clean energy use. The principles often get summarized as Additionality, Temporality, and Locality (ATL). A simple way to explain them uses the example of a party. Additionality is like buying extra beer for the party instead of taking beer from someone else’s fridge. You are bringing something new that changes the total available. Temporality is bringing the beer when people are actually thirsty, not the morning after, because timing matters to the experience everyone is having. Locality is bringing the beer to the party you are attending, not to a house across town, because benefit does not transfer across locations.

When companies claim clean electricity, these principles matter in the same straightforward way. Additionality ensures that the clean supply exists because the buyer’s action caused it to exist. Temporality ensures the clean supply appears at the same time as the consumption. Locality ensures the clean supply can influence the actual grid where the consumption takes place. Without these principles clean energy claims drift away from the physics of how electricity is generated and delivered.

My own relationship with ATL is at least somewhat nuanced. In the hydrogen sector I have a strong position that these principles are not optional. Electrolyzers draw large volumes of power at high capacity factors. If that power comes from a grid that is fossil-heavy in most hours, green hydrogen stops being green. For hydrogen production to provide a climate benefit, each of the ATL conditions needs to be met. The supply must be new or it will not change the grid mix. The supply must be aligned with the operating hours of the electrolyser or fossil plants will ramp to cover the shortfall. The supply must be in the same regional grid or the emissions avoided by a distant solar or wind installation will not match the emissions created by the electrolyzer’s local load. The European Union understood this early and built ATL logic into its renewable fuels standards. The United States was heading in the same direction through the Treasury rules for the 45V hydrogen credit, although their attacks on renewables and Blue state hydrogen have weakened decarbonized hydrogen requirements and actions considerably.

My ambivalence appears when we look at light electric vehicles, small commercial buildings, offices, or retail chains. These loads do not resemble hydrogen plants. A workplace charger with a 10 kW draw does not shift the marginal generator on a regional grid. A store or a bank branch with a few hundred kW of demand does not force a gas plant to ramp at night. These small or diffuse loads operate inside the noise of the system. Their procurement choices matter from a financial perspective, but their temporal mismatch with renewable generation does not materially influence grid emissions. The idea that every small business, school, or homeowner must match hourly renewables or purchase strictly local certificates does not survive a practicality test or a systems test. For EV charging in particular the key driver of decarbonization is the grid mix itself. As grids get cleaner, EVs get cleaner. The matching rules for individual chargers do not need to be as strict as those for an electrolyzer consuming tens or hundreds of MW continuously.

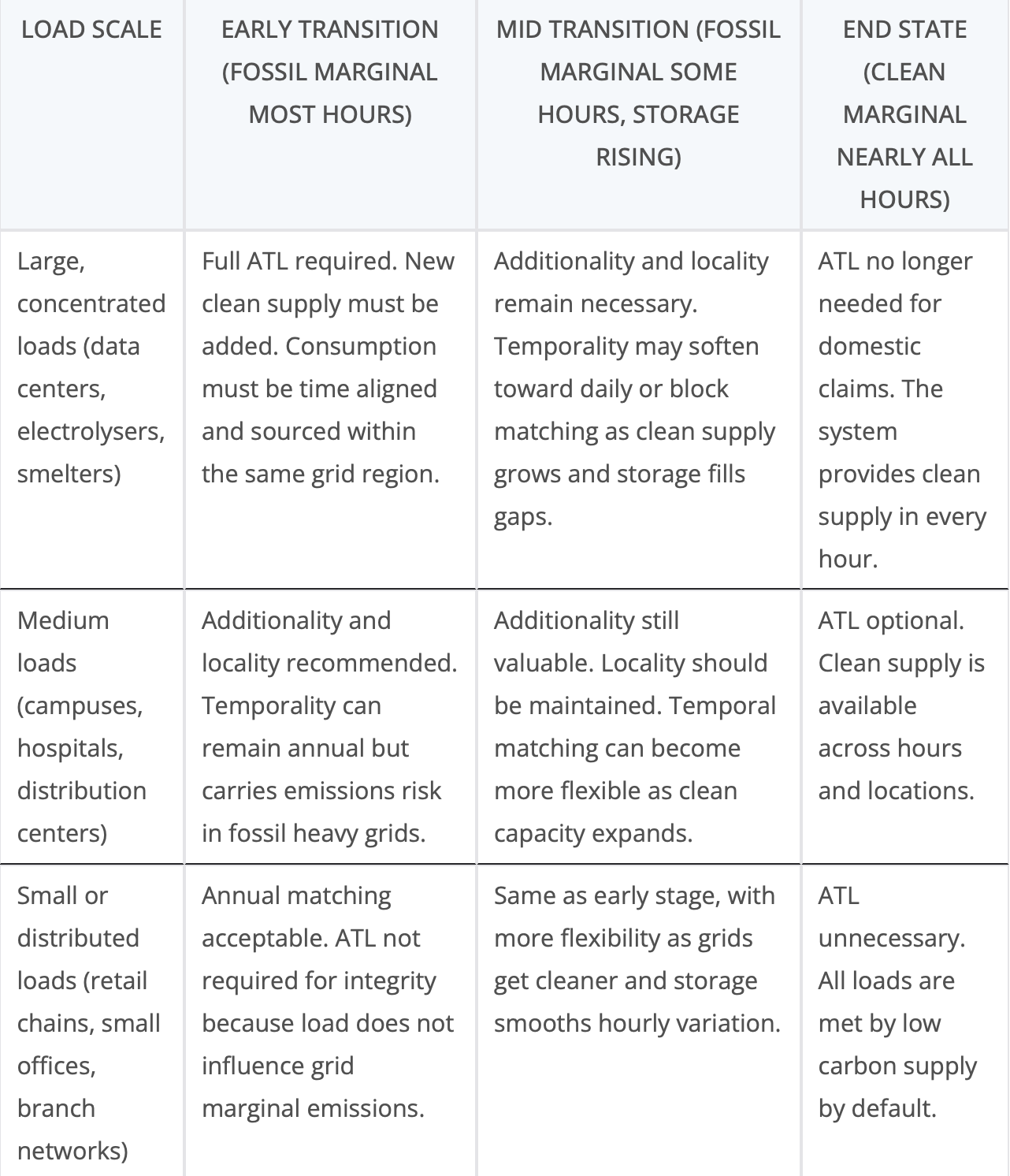

This difference suggests that a nuanced and tiered approach would deliver more accurate emissions accounting without imposing unnecessary burdens. Some loads are large enough and concentrated enough that their power demand changes grid behavior. These loads need the full ATL treatment. Very large data centers, industrial electrolysers, smelters, or synthetic fuel plants are in this group. They need new clean supply. They need clean supply in the hours they consume electricity. They need clean supply in the grid region where they operate.

A second group consists of medium-sized users like universities, hospitals, campuses, and distribution centers. Their demand is large but does not always reshape regional dispatch. They may benefit from Additionality and Locality without strict hourly matching.

A third group includes small or distributed loads whose individual impact is minimal. For them annual matching or market-based accounting provides enough accuracy without the administrative burden of ATL tracking. This three tier approach maps accountability to system impact. It keeps the focus on the places where temporal and locational mismatches create meaningful emissions. It avoids burdening loads that have no practical influence on marginal generation.

It is also important to see ATL not as a permanent set of constraints, but as transition rules that help steer electricity demand toward real climate benefit while grids decarbonize. These rules matter because today the marginal generator is still a fossil unit in many regions. New loads added without new clean supply increase emissions. Loads that consume power at night or during system stress often depend on gas or coal even when companies buy annual renewable certificates. Locality remains essential because a solar farm built in one grid region cannot offset fossil consumption in another. ATL translates these physical conditions into accounting guardrails. They keep corporate claims tethered to actual system impacts during the years when mismatches still have large consequences.

The relevance of ATL changes as grids clean up. Early in the transition, strict ATL requirements make sense for large loads that could drive significant fossil generation if left unmanaged. Electrolyzers, data centers, and large industrial electrification projects fall into this category. Over time, as storage scales, as clean firm generation expands, and as grids rely less on fossil units to meet marginal demand, the relationship between consumption timing and emissions weakens. Temporal rules can soften from hourly matching to daily or block matching once fossil units no longer operate continuously. Locational rules can broaden from strict regional matching to larger balancing areas as interconnected clean power becomes the normal condition rather than the exception.

A mature grid with minimal fossil generation makes additionality less central because every incremental unit of load is met by low carbon supply by default. The same grid maturity turns temporality into a secondary consideration because storage and clean firm resources smooth out intermittency. Locality loses its force when emissions converge across regions. In this end state, ATL does not disappear but fades into the background because the purpose it served in the transition has been achieved. The system itself carries clean power to every consumer in every hour. Accounting frameworks can simplify because physical reality has caught up with the climate claims companies want to make.

Some jurisdictions are already living in the end state that ATL rules are meant to create. Iceland is the clearest case because its grid runs almost entirely on geothermal and hydropower, which provide stable low carbon electricity in every hour of the year. A new data center, electrolyzer, or factory in Iceland does not drive fossil plant ramping because no fossil plants are present. There is no temporal mismatch to correct because clean supply is continuous, and there is no regional variation in emissions intensity because the entire country functions as a single clean balancing area. In this context ATL rules become redundant for activities inside Iceland’s borders. The system itself guarantees the integrity that accounting rules try to enforce elsewhere. This highlights the broader point that ATL is a transition framework, not an end state framework. Regions with fully decarbonized grids do not need compensating structures because physical reality already matches the climate claims companies want to make. Quebec and Norway could reasonably make this claim as well, although the scale of hyperscaler datacenters would challenge even their massive hydroelectric supplies.

Designing Scope 2 rules with this time dimension in mind would give the GHG Protocol a clearer long term structure. Early rules can stay tight to prevent backsliding and preserve integrity, while later rules can relax as the world crosses key decarbonization thresholds. This approach avoids burdening small consumers and keeps the focus on the loads that drive real emissions during the transition. It also reinforces the idea that justice, fairness, and practicality improve as grids get cleaner, because the need for compensating accounting structures declines when the underlying infrastructure is almost entirely low carbon.

The Trump Administration has shown little interest in this debate for reasons that are easy to understand. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol is voluntary, global, and outside the scope of domestic regulation. Tightening Scope 2 rules would make renewable procurement more complex and expensive for many companies. An administration that favors fossil fuel growth has no political incentive to defend or promote a standard that strengthens corporate emissions claims or accelerates private sector transition work. At the same time it cannot stop the GHG Protocol from evolving. The United States government has no authority over its process. The absence of commentary from the administration is better read as ignorance and relative lack of influence than of alignment or opposition. The debate will unfold regardless of who occupies the White House because the relevant stakeholders are multinational companies, investors, and standard setters rather than federal agencies.

The advocacy piece by WattTime and REsurety does not engage with the nuances of scale of demand or state of transition. Both firms argue against strong temporal or locational restrictions for all buyers rather than adopt a tiered system. This is understandable when we consider their revenue models. WattTime focuses on avoided emissions analytics across global markets. REsurety focuses on locational marginal emissions models for PPA buyers. Both approaches work best when companies have the freedom to procure renewables anywhere and at any time and still claim climate benefit.

Their arguments are not wrong on their own terms. Buying new renewables in parts of the world with coal-heavy grids does reduce global emissions. Locational marginal emissions data provides valuable insight into where renewables do the most work. The problem is that these claims do not always align with the claims companies want to make about their own electricity use. If a data center consumes fossil electricity at night in Ohio, a solar project in Chile does not change the emissions associated with that consumption. The global avoided emissions may still be positive, but the Scope 2 claim is not accurate. The lack of nuance in the advocacy piece comes from the desire to preserve global flexibility rather than confront which corporate loads require strict accounting and which do not.

And to be clear, my assertions are only about their published positions and the GHGP draft, not any internal discussions that have been had. I make no claim to thinking better than the people who live their professional lives in this space. It is highly probable that my argument for a framework that pragmatically treats different scales of loads and different domestic conditions differently has seen extensive debate within the community. There are arguments for simplicity, especially as it is a voluntary reporting framework for corporations.

The GHG Protocol revision is an opportunity to set clearer expectations for corporate electricity use during a transition period when grid conditions vary widely across regions. A tiered model acknowledges that not all loads are created equal and that the stage of grid decarbonization should shape what is required of different consumers. It preserves credibility for sectors like hydrogen where ATL remains essential in the early years of the transition, while keeping expectations manageable for smaller loads that have little influence on marginal emissions in any stage. It also respects the fact that grid physics treat a 200 MW electrolyzer in a fossil-heavy system and a 20 kW charger in a nearly clean system very differently.

The goal is not purity. The goal is accurate alignment between corporate claims and the physical impacts those claims imply as grids move from early transition to maturity. The voluntary market will remain important because the world cannot afford a retreat from clean energy commitments. The work ahead is to design accounting rules that reflect how energy systems behave today and how they will evolve as the transition progresses.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy