The LNG Detour: What Scotland’s New Ferry Teaches Us

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Scotland’s Glen Sannox was launched with fanfare as the country’s first “green” ferry, meant to reduce the impact of crossings between the mainland and Arran. It was designed as a dual-fuel vessel, running on either marine diesel or liquefied natural gas, with the promise of cleaner air and lower emissions. LNG was meant to cut sulfur and nitrogen oxides, improving local air quality around ports and coastal communities. On the climate side, it was expected to deliver measurable carbon savings compared to the older diesel ferry it would replace. Instead, it has become a case study in how assumptions and design choices can turn a well-intentioned project into a step backwards.

The Glen Sannox story is stretched across a decade. The order was placed in 2015 with Ferguson Marine, alongside its sister ship Glen Rosa, to replace aging diesel ferries on the Arran route. Delays in construction pushed the project far beyond its original schedule, with costs rising steeply as technical and contractual problems piled up. The vessel finally entered passenger service in January 2025, ten years after being commissioned. A year earlier, in January 2024, the ICCT released its Fugitive and Unburned Methane Emissions from Ships (FUMES) study, providing fresh evidence that methane slip from LNG engines was much higher than industry estimates. That coincidence sharpened the scrutiny of Glen Sannox, placing its climate performance under a harsher spotlight just as it began regular operations.

Coverage of Glen Sannox’s emissions centers on CalMac’s own analysis that put the LNG ferry at about 10,391 tons CO2e per year versus 7,732 tons for the older Caledonian Isles, a gap of roughly 35%. Those totals included LNG delivered by road tankers and methane slip. The underlying Annex A assumptions set weekly LNG burn for the main engines and auxiliaries and used about 1.296 tons of methane slip per week, which critics say is low relative to measurement literature.

Naval architect Euan Haig’s submissions to the Scottish Parliament questioned how methane’s time profile and decay were treated and argued that incomplete handling of boil-off and slip understates warming. The ICCT’s FUMES project added weight to those concerns by reporting average methane slip of 6.4% for low-pressure dual-fuel four-stroke engines, the same class aboard Glen Sannox, which would roughly double the slip compared to the Annex A input and lift weekly and annual CO2e.

CalMac and CMAL did not dispute the headline annual totals but said simple comparisons are misleading because Glen Sannox is larger, sails a longer interim route from Troon instead of Ardrossan, and was designed when LNG was seen as a reasonable transition choice. The result is an unresolved gap between measurement-based slip rates and the operator’s assumed slip that materially affects the ferry’s reported climate footprint. The combination led me to run some numbers myself.

The comparison vessel is the Caledonian Isles, which has connected Ardrossan and Brodick since 1993. That ferry carried up to 1,000 passengers and about 110 cars, consuming just under 3 million liters of marine diesel each year. Spread across a typical year, that translates to about 176 tons of CO2e per week, or 132 kilograms per nautical mile of service, when running its core timetable of five sailings in each direction per day. The Caledonian Isles was not efficient by modern standards, but it offered frequent and reliable service with a known emissions profile.

Glen Sannox is larger in some ways, with about 646 meters of vehicle lanes and capacity for at least 127 cars or 16 heavy trucks, though its passenger load was capped at 852 after safety reviews. It was meant to operate from Ardrossan as well, but harbor constraints forced it to shift to Troon, stretching the crossing from 55 minutes to 75 minutes. That shift cut the possible daily return trips from ten to six. In practice, this means fewer sailings for the community and more emissions per passenger or vehicle served. The larger ship is working harder, but not necessarily serving more people.

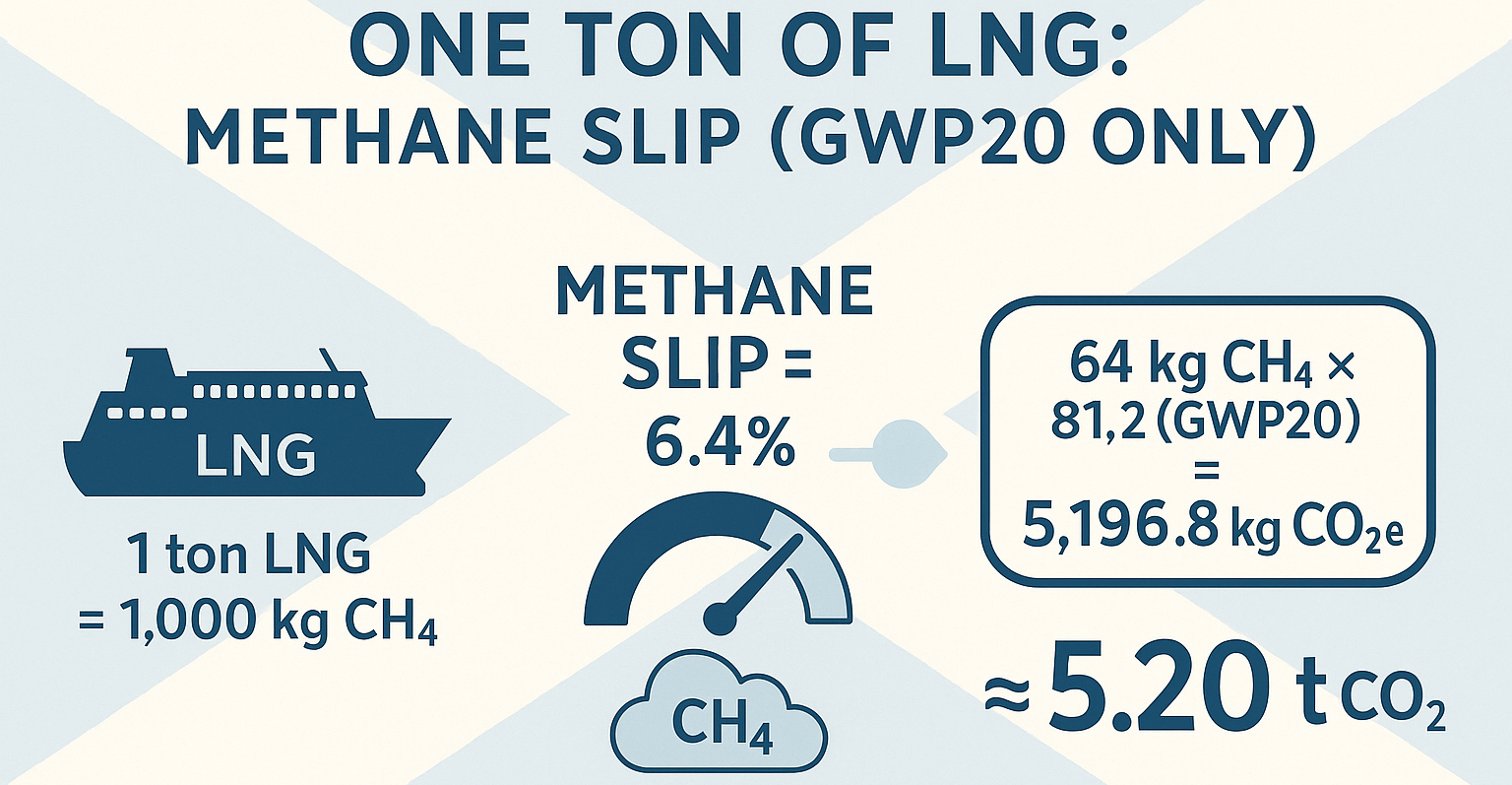

The problem is not just the schedule. It is the nature of LNG itself. Burning methane produces less CO2 per unit of energy than diesel, but LNG engines do not combust all of it. Some methane escapes unburned from the cylinders and the exhaust, a phenomenon called methane slip. Methane is a far more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2 over 20 and 100 year timeframes, so even small percentages of slip can tip the balance. The Scottish Government’s Annex A report on Glen Sannox, published in early January 2024, assumed methane slip of about 1.3 tons per week. That figure was accepted as reasonable until the International Council on Clean Transportation’s FUMES study published measured data two weeks later. Their researchers found that low-pressure dual-fuel four-stroke engines, the same family installed in Glen Sannox, slipped an average of 6.4% of methane, nearly double the optimistic estimates.

That single adjustment changes the climate ledger. Glen Sannox burns about 44.5 tons of LNG per week in its main engines and generators, producing about 122 tons of CO2. If you assume 1.3 tons of methane slip, that adds 35 tons CO2e on a 100 year basis or 105 tons on a 20 year basis. Total emissions land at 157 tons CO2e per week on the long term metric or 228 tons on the short term. Compared to Caledonian Isles’ 176 tons, Glen Sannox looks slightly better on the 100 year view and worse on the 20 year view. But if you apply the FUMES average of 6.4% methane slip, the picture shifts further. That would mean 2.85 tons of methane escaping each week. At 27 times the warming effect of CO2 over 100 years, that adds about 77 tons CO2e, pushing total weekly emissions to 199 tons. On the 20 year horizon, the methane is worth 231 tons CO2e, making the ferry’s weekly total over 353 tons. That is more than double the predecessor’s emissions for the same distance traveled.

When viewed per nautical mile, the old diesel ferry produced about 132 kilograms of CO2e. Glen Sannox under its official assumptions ranges from 118 to 171 kilograms per mile, depending on whether you choose 100 or 20 year timeframes. Under FUMES based assumptions, the range is 150 to 266 kilograms per mile. In other words, using more realistic slip data makes the LNG ferry clearly worse on a long term basis, and disastrous on a short term one. LNG has improved local air quality by reducing sulfur and nitrogen oxides, but at the cost of higher greenhouse gas emissions. For a project that was supposed to lead Scotland toward lower carbon shipping, this is a sobering reversal.

Glen Sannox is not an outlier in the LNG story. Across the maritime sector, LNG has been marketed as a transitional fuel that balances cost, compliance, and sustainability. Yet independent studies keep finding that the benefits are overstated when methane slip and supply chain emissions are included. Upstream leakage during extraction, processing, and liquefaction of natural gas adds another layer of warming that is not visible at the smokestack. Owners and operators are discovering that what looked good on a narrow regulatory measure does not hold up under full lifecycle accounting. Worse, every dollar invested in LNG bunkering and dual-fuel engines is money not spent on technologies that can actually meet climate goals.

Meanwhile, the fully electric end of the market is scaling to major-route distances. Buquebus’s 130 m China Zorrilla is set for the Buenos Aires–Colonia corridor, a roughly 27–32 nautical mile crossing, carrying about 2,100 passengers and 225 vehicles on a battery pack just over 40 MWh with charging at both terminals. Finland’s Viking Line is advancing the Helios all-electric concept for the 43 nautical mile Helsinki–Tallinn run, pairing a 195 m hull, about 2,000 passengers, roughly 2,000 lane meters, and an 85–100 MWh battery bank with frequent terminal charging. On the Pacific coast, BC Ferries’ new major hybrid-electric vessels are being procured to operate fully electric once shore power is in place on its busiest corridors, including about 24 nautical miles on Tsawwassen–Swartz Bay and about 30 nautical miles on Horseshoe Bay–Departure Bay, distances squarely inside today’s battery-ferry envelope with megawatt-scale fast charging.

The lesson is clear. Technology choices cannot be judged on tailpipe emissions alone. For shipping, real sustainability will come from a combination of electrification on short routes, advanced biofuels where energy density is required, and eventually broader adoption of zero carbon fuels where they make economic sense. LNG was sold as a bridge, but in practice it is a detour. Glen Sannox shows how ambition and intent can be undone by relying on optimistic assumptions instead of empirical data. The FUMES study is a reminder that real measurements matter, and that policies and investments should be grounded in observed performance, not marketing claims.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy