Airbus Drops Hydrogen As Aviation Industry Admits It Won’t Fly

Hydrogen’s hoped for role in aviation dates back to the mid-20th century, when researchers began exploring its potential as an alternative to conventional jet fuel. In 1957, engineers at Lockheed and Boeing investigated hydrogen propulsion as part of Cold War efforts to develop high-altitude, long-endurance aircraft. In 1959, a modified Martin B-57 Canberra successfully flew with one engine running on liquid hydrogen. In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union flew the Tupolev Tu-155, a modified Tu-154 airliner that became the first jet aircraft to fly solely using liquid hydrogen.

Following the Cold War, interest in hydrogen aviation waned as jet fuel remained inexpensive and dominant. However, growing concerns over climate change and carbon emissions reignited research into hydrogen propulsion in the 2000s. Boeing made headlines in 2008 with the first successful flight of a small aircraft powered entirely by a hydrogen fuel cell. In the 2010s, European aerospace leaders, including Airbus, began seriously exploring hydrogen as a long-term solution, culminating in the 2020 unveiling of Airbus’ ZEROe concept — three hydrogen-powered aircraft designs aimed at commercial service by 2035. Meanwhile, startups such as ZeroAvia and Universal Hydrogen were trying to develop retrofits for regional aircraft. Wright Electric had hydrogen as one of its possible power sources, along with the equal dead end of aluminum air batteries.

By 2017, I’d already assessed most modes of transportation and eliminated hydrogen as an option. I hadn’t gone deep on rail, maritime shipping, and aviation at the time, so thought there might be a role for hydrogen in those modes. Subsequently, I’ve done the work on each as well as more work on the inherent costs and challenges of hydrogen and concluded hydrogen has no part to play.

As I said to someone engaged with and invested in ZeroAvia in a conversation recently, in 2017 I hadn’t assessed the certification challenges, the storage challenges, the airframe challenges, the balance of aircraft during flight challenges, the cost challenges, or the airport infrastructure challenges. Since then, I have.

I summarized the key points in an article a couple of years ago after being asked to participate in a UK academic panel on the subject with panelists who had been working in the space for decades and were too invested to accept reality.

One of the biggest challenges is low energy density by volume. While hydrogen has high energy per kilogram, it takes up far more space than jet fuel, requiring much larger and heavier tanks. This extra bulk increases drag and reduces aircraft efficiency, limiting range and passenger capacity.

Another major obstacle is cryogenic storage. Liquid hydrogen must be kept at -253°C, demanding highly insulated tanks that add weight and complexity. Unlike jet fuel, which can be stored in an aircraft’s wings, hydrogen requires separate, heavily reinforced tanks, making aircraft design more challenging.

The lack of infrastructure further complicates hydrogen’s viability. Airports worldwide are built around jet fuel, and transitioning to hydrogen would require massive investments in production, storage, and refueling systems. The cost and logistical challenges of such a shift make large-scale adoption unlikely in the near future.

Safety is also a concern. Hydrogen is highly flammable, and while modern containment systems reduce risks, the aviation industry would need to develop new safety protocols. The added precautions required for handling and storing hydrogen make implementation more difficult and costly.

Finally, the economics don’t add up. Developing new aircraft designs, overhauling airport infrastructure, and ensuring safety compliance would be extremely expensive. With more practical alternatives like sustainable aviation fuels and battery-electric aircraft emerging, hydrogen can’t compete.

What will work? Well, for a start, lower demand growth than official projections from IATA and Boeing, which were telling everyone that aviation demand growth was going to follow the curve from 1990 to 2019, with compounded annual growth rates of 3% to 4%.

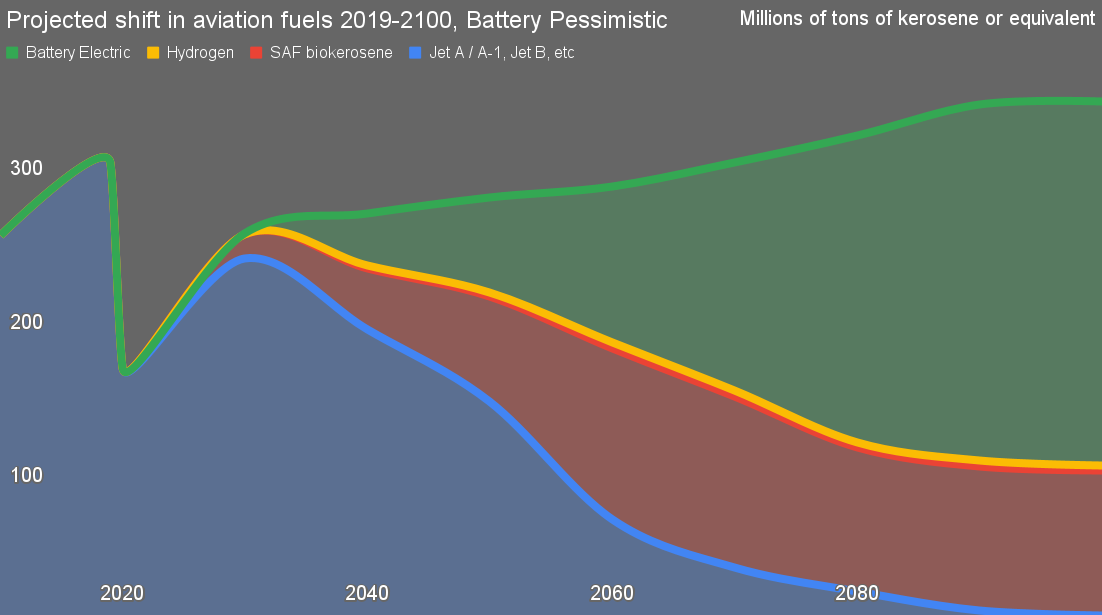

My projection, lightly updated in mid-2024, is much less rosy for growth and sees battery-electric, hybrid electric and SAF biofuels providing the energy required for all aviation. Battery and hybrid electric will dominate most in-continent flights, with up to 100-passenger turboprops traveling up to 1,000 km flights. In most cases, the hybrid biofuel generator will only be required for divert and reserve. Crossing oceans will still require SAF biofuels, but even there hybridization will be the norm, with things like the auxiliary power unit already shifting to battery-electric today. It’s in this context that recent news out of the aviation industry falls.

One of my predictions for 2025 is that there will be a bloodbath in the hydrogen for transportation segment. At the end of the year, I have to figure out if I’m right or not, so I compiled a list of firms in the space, currently totaling 115. The table above is the aviation segment, with twelve firms represented. I’m sure I missed a couple, so please do point them out to me so I can add them to the list. A high risk rating means that they are likely to be defunct in the next year or two. A low rating — there’s nothing in between in aviation — means that while they are going to lose money, they aren’t putting the entire firm at risk due to their efforts. For completeness, a medium risk means that they are going to lose sufficient money that they could go out of business entirely.

First out of the space was Wright Electric. It released a white paper a few years ago with options for powering aviation, and by 2021 had figured out that batteries and hybrid biofuels were going to do the job and abandoned hydrogen. Straightforward techno-economic analysis for the win because the company didn’t bother to waste a lot of time and money on hydrogen.

Universal Hydrogen, a startup founded in 2020 by former Airbus CTO Paul Eremenko, aimed to decarbonize aviation by retrofitting regional aircraft with hydrogen fuel cell powertrains and developing a modular hydrogen distribution system. In March 2023, the company successfully flew a modified Dash 8 powered by hydrogen. Universal Hydrogen ceased operations in June 2024 due to financial challenges. The hydrogen pods were one of the worst ideas I’ve heard of recently, so it’s unsurprising it was off the market early.

Among the majors of Airbus, Boeing, Embraer, and COMAC — China’s major civil aviation firm — the efforts were relatively tiny, albeit promoted heavily by Airbus at least, with its three concept planes being perhaps the highest profile initiative. Now Airbus has ‘suspended’ all efforts into hydrogen, finally realizing after wasting a lot of engineers’ time what was obvious from straightforward analysis. Many observers have tended to suggest that the manufacturers just aren’t serious about decarbonization, and that might be true.

The news about Airbus withdrawing from the hydrogen game came days after the new Destination 2050 roadmap dropped. The roadmap is backed by five major European aviation associations, collectively representing thousands of companies across the sector. Airlines for Europe (A4E) represents over 3,600 aircraft and nearly 2,100 destinations. Airports Council International Europe (ACI Europe) covers 600+ airports handling 90% of Europe’s air traffic. The Aerospace, Security and Defence Industries Association of Europe (ASD) represents over 4,000 companies, accounting for 98% of the industry’s turnover. The Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO) supports over 90% of global air traffic through air navigation service providers and industry suppliers. Lastly, the European Regions Airline Association (ERA) includes 50+ airlines and around 150 companies involved in regional air transport. It’s basically everyone involved in aviation in Europe, and a lot of them are global.

The roadmap charts a path for European aviation to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Originally, hydrogen-powered aircraft were projected to contribute 20% of emissions reductions, but the recent drop revised this down to just 6%, citing delays in technological readiness and adoption. As a result, the plan now leans more heavily on sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), operational efficiencies, and market-based measures to drive decarbonization, with a compound annual growth rate of 1.4% — well under the 3% to 4% IATA and Boeing predict — in passenger traffic factored into emissions reduction strategies. Undoubtedly IATA and Boeing are hoping for massive growth in the developing world to make up for limited growth in Europe, but as decarbonization is going to jack ticket prices and high speed rail and virtual meetings continue to grow, I suspect they’ll be proven wrong.

An easy prediction for me is that with aviation major Airbus dropping out and the other three majors doing very limited demonstrators and R&D, that 6% will drop to 0% in the coming years. The rest of the majors will drop their limited efforts and the startups will simply go bankrupt, most this year. That’s good, actually, as hydrogen remains a potent, if indirect, greenhouse gas 12-37 times stronger than carbon dioxide over 100 and 20 years respectively, and hydrogen leaks 1%+ at every touchpoint in supply chains.

The bloodbath in hydrogen for aviation is shaping up nicely, as is the electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) bloodbath. Real decarbonization efforts like battery-electric hybrids and SAF biofuels can get more attention now.

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Whether you have solar power or not, please complete our latest solar power survey.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy