The Sodium-Ion Battery Is Coming To Production Cars This Year

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Lithium is abundant, but difficult to extract and purify for use in batteries. Last year, the price of lithium carbonate peaked at over $80,000 per ton, although it has come down considerably since then. Oddly enough, people who don’t bat an eye about oil and gas wells within a few feet of homes and schools are losing their minds about the horrors of lithium mining. It should be noted that no lithium mining takes place next door to homes and schools, but common sense and logic are not prevalent among the fossil fuel crowd.

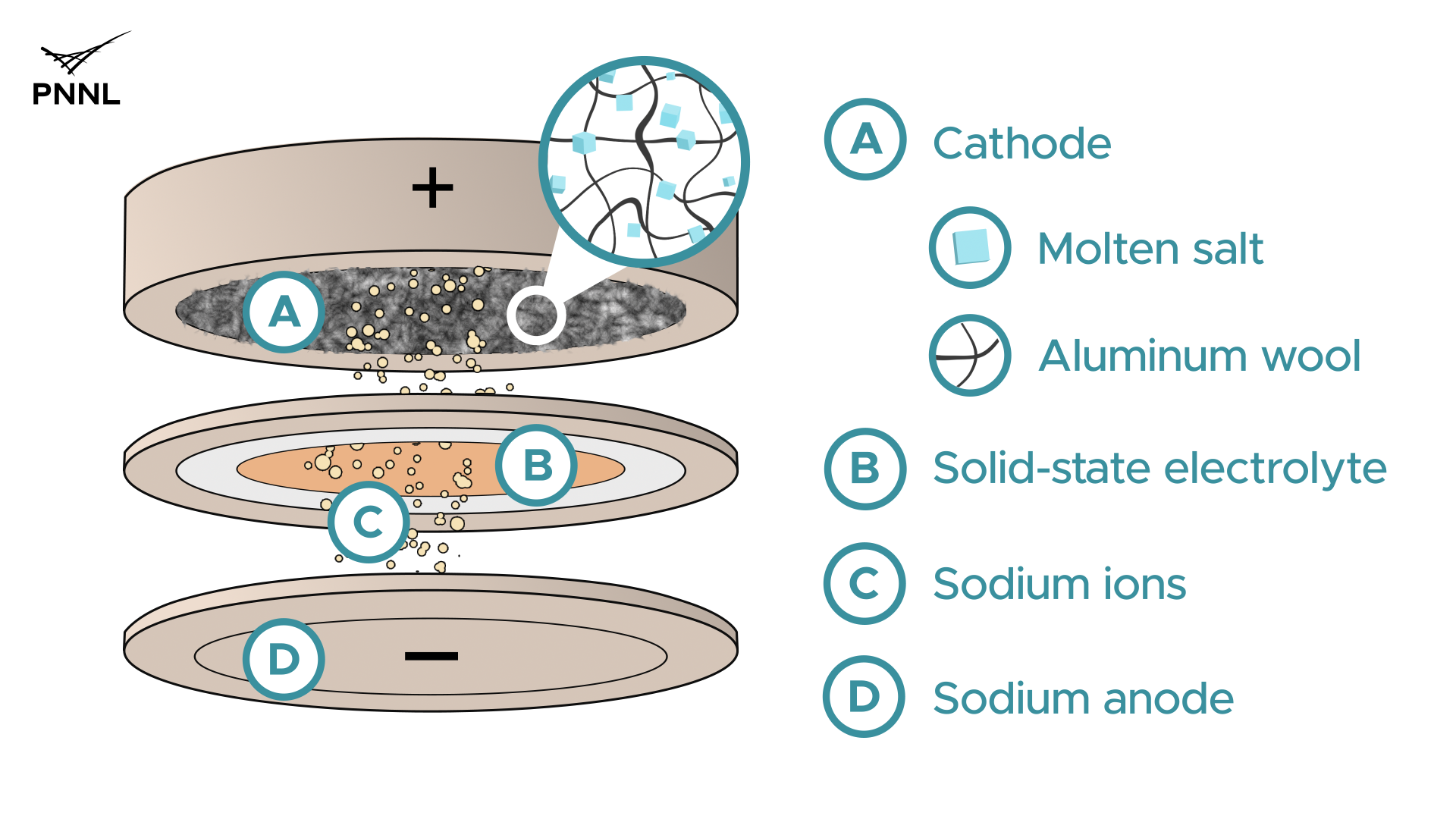

Sodium is also abundant, but unlike lithium, is readily available. For instance, the price of sodium carbonate is around $300 per ton today. Sodium — one of the primary components of table salt — is chemically similar to lithium, and thanks to the explosion in lithium carbonate prices, many companies are researching ways to use it to replace lithium in the batteries for electric vehicles.

Despite being chemically similar, sodium-ion batteries today have considerably lower energy density than lithium batteries. That’s a detriment, but bear in mind that not too long ago, LFP batteries were woefully deficient in their energy storage capability. But today’s LFP batteries are nearly as energy dense as lithium-ion batteries were just a few years ago. Things are moving quickly in battery development. The sodium-ion batteries available today will likely improve just as quickly.

On the other hand, sodium batteries are much less affected by low temperatures and appear to be able to handle more charge/discharge cycles than lithium-ion batteries. The latest sodium batteries do not require scarce materials like cobalt and nickel. Both CATL and BYD say they are about to introduce EV battery packs that have a mix of lithium-ion and sodium-ion cells. The thinking is the sodium cells will address the low temperature performance issue and the lithium cells will take care of the need for good performance in daily driving.

At the Shanghai auto show this week, CATL said its sodium-ion batteries will be installed in the Chery iCAR due to go on sale by the end of this year, according to CnEVPost. BYD sources say its sodium-ion battery will also be in mass production in the second half of the year beginning with the Seagull. BYD introduced the Seagull in Shanghai this week. Fitted with LFP batteries, it is available in three versions with pre-sale prices of $11,450, $12,200, and $14,000 respectively. The new models use BYD’s Blade batteries of 30.08 kWh and 38.88 kWh capacity. Prices for cars equipped with sodium-ion batteries have not yet been announced.

China & Sodium-Ion Batteries

The New York Times points out that because sodium-ion batteries have lower energy densities, more of them are needed to equal the energy capacity of lithium-ion batteries. That means more space is needed for a given amount of energy. That’s a problem for use in vehicles, but not an issue for grid-scale battery storage. Utilities that switch from lithium to sodium can simply put twice as many big batteries in an empty lot near solar panels or wind turbines, the Times says.

The Inflation Reduction Act passed by Congress last August was designed primarily to offset China’s dominance of lithium-ion battery production worldwide. The New York Times says a switchover to sodium-ion batteries may make China’s control over battery manufacturing even greater.

Of the 20 sodium battery factories now planned or already under construction around the world, 16 are in China, according to Benchmark Minerals, a consulting firm. In two years, China will have nearly 95 percent of the world’s capacity to make sodium batteries. Lithium battery production will still dwarf sodium battery output at that point, Benchmark predicts, but advances in sodium are accelerating.

There is one problem for China, however when it comes to manufacturing sodium batteries. It controls much of the sources for lithium worldwide, but has little access to the soda ash that is the source for the sodium needed to manufacture batteries.

The United States accounts for over 90% of the world’s readily mined reserves for soda ash. According to the New York Times, beneath the southwestern Wyoming desert there is a vast deposit of soda ash that was formed 50 million years ago. For centuries, it has been mined to meet the needs of America’s glass manufacturing industry.

With minimal natural reserves of soda ash and a reluctance to rely on imports from the United States, China instead produces synthetic soda ash at chemical plants fueled by coal. Yes, you read that right. China will power its sodium-ion business with coal. We swear we are not making this up!

As if that wasn’t bad enough, China’s synthetic soda ash industry has a record of hazardous water pollution, which includes the collapse of a pile of alkali slag in east-central China in 2016 that washed away cars and fouled a major river. The country’s environment agency is working to clean up the industry.

Utility companies are notoriously risk adverse when it comes to new technology. They prefer tried and true solutions that have stood the test of time. The Times says the industry wants to know more about the durability of sodium-ion batteries, such as how well they perform after years outdoors, not just in labs, said David Fishman, a power sector consultant at Lantau Group, a consulting firm.

But Fishman and others are now watching sodium battery development closely. Demand for batteries is growing fast, and lithium is unlikely to remain the dominant material indefinitely.

The Takeaway

Sodium is an attractive alternative to lithium because it costs only 2 to 3% as much as lithium. Imagine what that price difference could mean to the price of new electric vehicles! It is also largely immune to the decrease in performance that bedevils lithium-ion batteries today. But sodium-ion technology is about where lithium-ion technology was a decade ago.

That doesn’t mean it won’t get better over time, but it does suggest there are a lot of things that can happen in the meantime. For instance, the price of lithium could continue to decline as new sources are discovered and the fruits of the IRA begin to kick in.

The fact that there is so much soda ash available in the US is probably the primary reason to pursue sodium-ion technology. If America wants to decouple from China when it comes to batteries, sodium may be the route to go. But as the New York Times points out, virtually all the basic research into sodium-ion batteries is taking place in China at the present time.

That has to change if America wants to steal a march on its newest adversary, but will it? From everything we hear at the CleanTechnica communications center, nobody outside of China is paying much attention to the possibility of using sodium-ion batteries for vehicles or energy storage, although the DOE is conducting some research on the subject. In China, dozens of government funded labs are working on sodium batteries. Ten years from now, America may once again have reason to bewail its reliance on Chinese battery technology and demand to know, “What happened?”

Sign up for CleanTechnica's Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott's in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy