Global Vulnerability To The Disruption Of Undersea Cables Exposed

All of us today are concerned by the news that a software update gone awry was responsible for the interruption of computer communications around the world. The update was intended to enhance computer security systems, but it had an unexpected result. It made it abundantly clear how vulnerable human society has become to any interruption in the digital communications systems we depend on, many of which are dependent on undersea cables.

According to the New York Times, a series of outages rippled across the globe as information displays, login systems, and broadcasting networks went dark. Critical businesses and services, including airlines, hospitals, train networks, and TV stations, were disrupted by a global tech outage affecting Microsoft users. In many countries, flights were grounded, workers couldn’t access their systems, and in some cases, customers were unable to make credit card payments in stores.

CrowdStrike, the company responsible for the software update, quickly identified the problem and took corrective action. No planes fell out of the sky, no autonomous vehicles careened into each other, and no AI-enabled robots went crashing into walls. Perhaps the major lesson from the whole thing is that we have made ourselves more dependent on digital networks than most people realize.

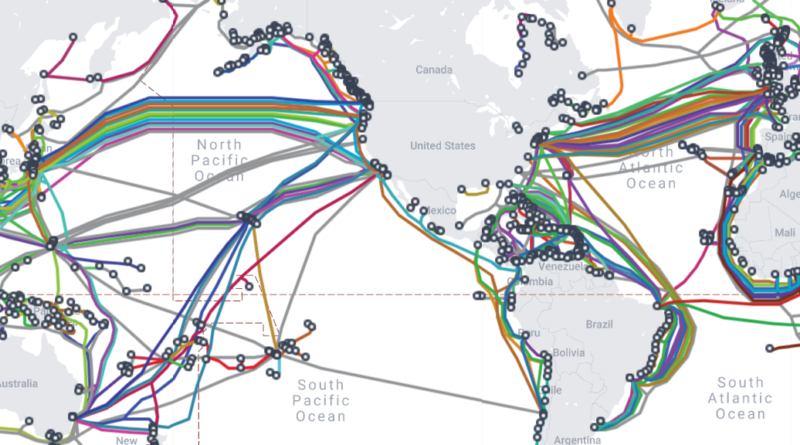

Vulnerable Undersea Computer & Internet Cables

Today, there are tens of thousands of undersea cables for computer and internet services that connect the continents. The idea is not new. The first transatlantic telegraph cable was installed beginning in 1854, beginning in Valentia Island off the west coast of Ireland to the Bay of Bulls, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. The first communications occurred on August 16, 1858. We tend to think that most digital intercontinental digital traffic is done via satellites — isn’t that what Ted Turner taught us how to do? — but in fact 99% of intercontinental traffic is transmitted via undersea cables. That’s a problem, because those cables are a critical part of global communications but are subject to sabotage anywhere along their length.

In a report on July 11, 2024, Bloomberg tells how a portion of a 31-mile long undersea cable off the coast of Norway went missing several years ago. The cable transmitted signals from five underwater microphones that are part of the Lofoten-Vesterålen Ocean Observatory, otherwise known as LoVe. The system is mostly a scientific tool that tracks the movement of whales, fish, and other marine life, but it is also used by the Norwegian military to identify ships in the area. As we learned in Tom Clancy’s The Hunt For Red October, every vessel has a distinctive sound signature. A sophisticated data analysis of those signatures at the time the cable stopped transmitting data showed one particular vessel — a Russian trawler named Saami — directly above the cable at that precise moment in time. The same analysis showed the Saami had made several passes above the cable in both directions before the break occurred — a pattern inconsistent with normal activity by a trawler that was actually trying to catch fish.

“We are talking about thousands and thousands of kilometers of infrastructure between Europe and the United States and Asia,” Katarzyna Zysk, a professor of international relations and contemporary history at the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies in Oslo, told Bloomberg. “This is a network that is extremely hard to surveil, to monitor, and to protect. This is infrastructure that is highly vulnerable to sabotage.”

Normally, when an undersea cable is damaged, it is because of a dragging anchor from a large ship or from the barn-door-like appendages that trawlers attach to their nets to keep them open as they are dragged through the water. The damage they cause usually rips the cables apart. It took 18 months to secure a vessel capable of accessing the site of the break in the LoVe cable into position. After several attempts, the severed end of the cable was located six miles away. When it was brought to the surface, it was apparent the cable had been cleanly severed by something like a saw blade. This was no accident, in other words.

A Second Undersea Cable Is Severed

At 5 am on Friday, January 7, 2022, a 900-mile long communications cable running from the Norwegian mainland to the far northern island of Svalbard stopped working. It was one of two cables servicing the Svalbard Satellite Station, the world’s largest ground station for collecting data from polar orbiting satellites, including meteorological and other imagery that has dual civilian and intelligence uses for American and European government agencies. The technicians from Space Norway, the company that operates the cables, determined later that water had somehow gotten into one of the cables, causing an electrical short.

The incident could have been an accident. However, when the cables had been laid in 2004, Space Norway had taken the precaution of burying them beneath the seafloor in shallow areas where there was a risk of damage by fishing trawlers. Cutting the cables, in other words, meant first digging through 6 feet of protective mud. On January 30, 2022, three weeks after the outage, when an underwater drone went down to investigate the damage the cameras revealed deep trenches in the seabed above the cables. Officials said the gashes could have been dug by the steel doors of a fishing net. Finding the exact coordinates of the cable and digging down to the cables themselves, as someone had in this case, would take many passes — sustained activity that suggested intent.

Journalists with the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation later determined that a Russian-flagged fishing trawler, the Melkart-5, had crossed the path of the cable 130 times at about the time it was damaged. One expert, speaking in a documentary film jointly produced by a group of Nordic public broadcasters, described the ship’s pattern of movement as “completely illogical.” Murman SeaFood Co., the Russian company that owns and operates the Melkart-5, said the ship was trawling in a permitted fishing zone when the cable was damaged and its movements that day were “totally normal.” Andrei Roman, a legal and economic aide to the company’s director, said, “We have nothing to do with this. Our ship didn’t violate any laws.”

To Katarzyna Zysk, the slicing of the marine institute’s cable and the damage to the Svalbard cable bear the hallmarks of Russian intelligence operations. She hypothesizes they could have been relatively simple — and deniable — ways to weaken parts of Norway and NATO’s intelligence gathering infrastructure, while perhaps serving as training exercises for Russian operatives specializing in sabotage of undersea cables. Or they could simply have been a way for Moscow to demonstrate to officials in Oslo that their underwater infrastructure — from data cables and power lines to petroleum drilling platforms and pipelines — is vulnerable. That type of behind the scenes signaling and posturing is common for spy services, which do things like openly trailing suspected spies to send a message that they’re being watched, she says.

Both incidents involved cables with specific significance to the Norwegian military, rather than transcontinental ones that might provoke a more forceful NATO response. In Zysk’s description, that’s a sign of calibrated provocation. The “extremely unlikely and unconventional” behavior of Russian flagged ships in both cases, she says, combined with “our knowledge about Russia using civilian trawlers for intelligence operations,” make the incidents highly suggestive. “The probability that this was intentional damage is very high.”

The Takeaway

It’s no surprise that Russia might be involved in damaging undersea cables. That’s not the point. The point is that we have come to rely on digital communications for every aspect of our daily lives. We expect the system to work seamlessly and flawlessly all day, every day. What happened this week when CrowdStrike attempted a routine software upgrade should be a warning to us that our digital world is very fragile and not particularly secure. Something to keep in mind as we set sail into a new era of digital systems controlled by artificial intelligence.

More than communications are involved. There are proposals to build solar farms in North Africa and send the electricity to Europe via an undersea cable near the strait of Gibraltar. Another involves sending electricity from northwest Australia to Indonesia, where it could be used to power lithium or nickel refining for the batteries in electric vehicles. Who will secure those cables if they are installed? And if they fail — whether by accident or design — do we have robust plans for how to carry on with our digital lifestyle for hours, days, weeks, or even months? If not, we are setting ourselves up for massive disruptions to our security and our economy. Out or sight, out of mind is not an appropriate plan for protecting the digital realm we have created.

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica's Comment Policy