Zero Is The Hero: Zero Net Energy Buildings Reach New Communities, Promising Savings & Renewable Energy

Originally published at ilsr.org by ILSR summer intern Matthew Douglas-May.

As energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies continue to improve both functionally and economically, Zero Net Energy (ZNE) buildings are spreading in communities around the country. The energy savings and environmental benefits of ZNE buildings, which produce as much energy using on-site renewables as they consume, are catching the attention of city leaders, regulators, and individuals nationwide.

In May 2017, Santa Clara, California, became the first city in the world to include ZNE requirements in its building code, requiring all new single-family residential construction to be ZNE. Cambridge, Massachusetts, plans to follow Santa Monica’s footsteps with goals to phase in ZNE in all new construction between 2020 and 2030 starting with commercial buildings and finishing with energy intensive laboratories. These moves follow statewide goals set in 2007 by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) for all new residential construction to be ZNE by 2020 and all new commercial construction to be ZNE by 2030. Many other cities like Fort Collins, Colorado, and Austin, Texas, have also made ZNE plans and goals.

On the national level, the New Buildings Institute (NBI) estimates that the number of “ZNE certified and emerging projects” increased by 74% in 2016 alone.

Why Zero Net Energy?

The shift toward ZNE buildings is well underway, but what are the benefits and the costs it brings?

The energy drawn from the grid and consumed by a ZNE building, including electricity, natural gas, hot water, and others, is matched over the course of a year by electricity generation from on-site renewables, usually solar. In addition, energy efficiency measures reduce these buildings’ energy needs and costs. In the 41 states, four territories, and Washington, D.C. where building owners can sell solar energy back to the grid with net metering, ZNE buildings will essentially have no energy bill, or even receive net revenue from surplus solar generation, promising significant savings for renters, owners, and all building stakeholders. Still, the energy-efficient appliances, special building design, and solar panel installations make ZNE buildings more expensive upfront than non-ZNE buildings. The big question is, do overall ZNE savings offset the greater price of the buildings themselves? Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

Chip in a few dollars a month to help support independent cleantech coverage that helps to accelerate the cleantech revolution!

The City of Santa Monica invested in a cost effectiveness analysis for its new ZNE building code, which shares some insights. The study uses two methods to examine ZNE energy savings against installation and maintenance costs for single-family homes, low-rise multifamily residences, and nonresidential buildings.

The first method of analysis uses Time Dependent Valuation (TDV), which takes into account the burden of peak demand in the cost analysis, and considers the savings for customers and society in the benefits analysis. The second method uses “customer retail rates for electricity and natural gas,” which only takes into account installation and maintenance, current retail prices for grid energy consumed, and solar energy sold back to the grid. Based on TDV, ZNE was cost effective for Santa Monica, delivering total savings that more than doubled the costs for all residential and commercial buildings. Santa Monica’s ZNE commercial buildings also proved cost-effective based on customer retail rates, while single-family homes and low-rise multifamily buildings recovered 90% of ZNE costs through energy savings over time. One important caveat noted in the study is that the most costly features of the ZNE design — the energy efficient heating, cooling, and insulation — did not generate as much energy savings because Santa Monica’s climate requires little heating or cooling. While this tempers results in Santa Monica, less temperate climates could greatly benefit from these products.

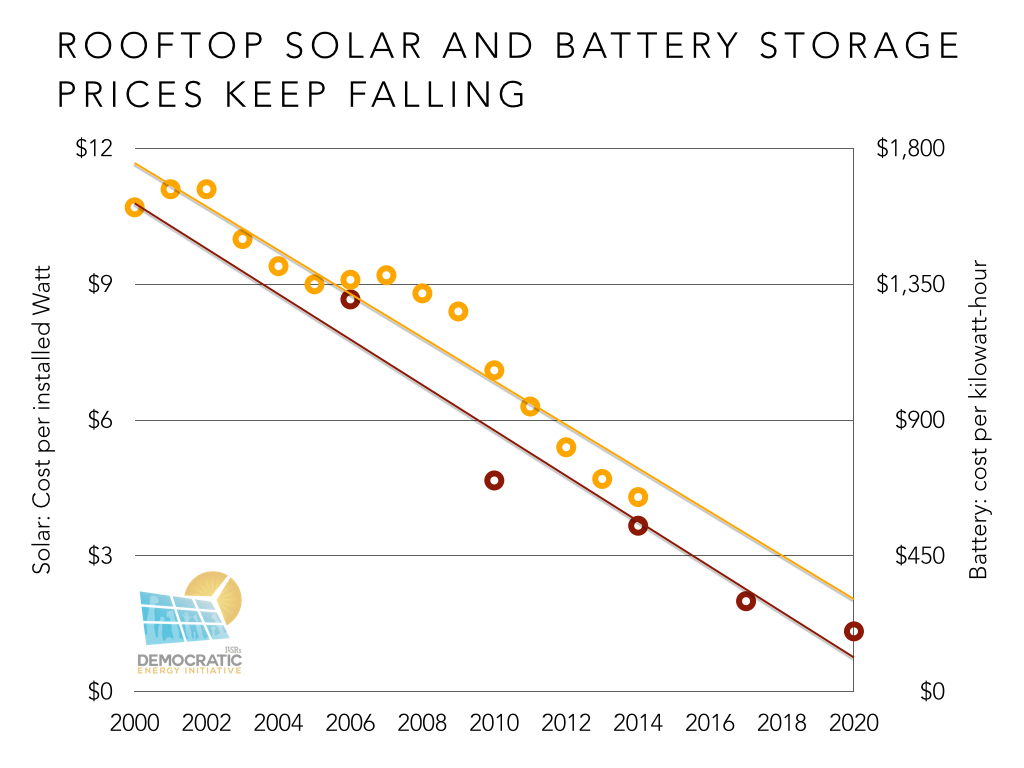

Constructing cost-effective ZNE buildings is very possible with today’s technologies at today’s prices. As solar installations and energy efficiency technology (as well as battery storage) continue to fall in price, and ZNE design improves, ZNE stands poised to become consistently cost effective.

Importantly, ZNE also offers a number of community benefits largely ignored in cost effectiveness studies. Making solar electricity generation a part of each building supports distributed generation and the economic benefits that come with it. Instead of utility companies extracting money from local economies with every energy bill, ZNE buildings, with no energy bill and an opportunity to support local solar and energy efficiency jobs, will keep those energy dollars local. In addition, ZNE buildings add value to the local housing and building market, and save community members money over time — cash they can spend elsewhere in the local economy.

On a broader scale, cities across the country are increasingly committing to clean energy goals, but often lack specific plans to achieve those goals. According to the US Energy Information Association, the residential and commercial sectors accounted for 40% of total energy consumption in the US in 2016. Adopting ZNE at a citywide level, or even just in municipal buildings, can serve as a defined step in a plan to achieve a city’s clean energy goals and rein in one of its biggest sources of energy consumption.

The (More Than Net Zero) Power of Building Codes

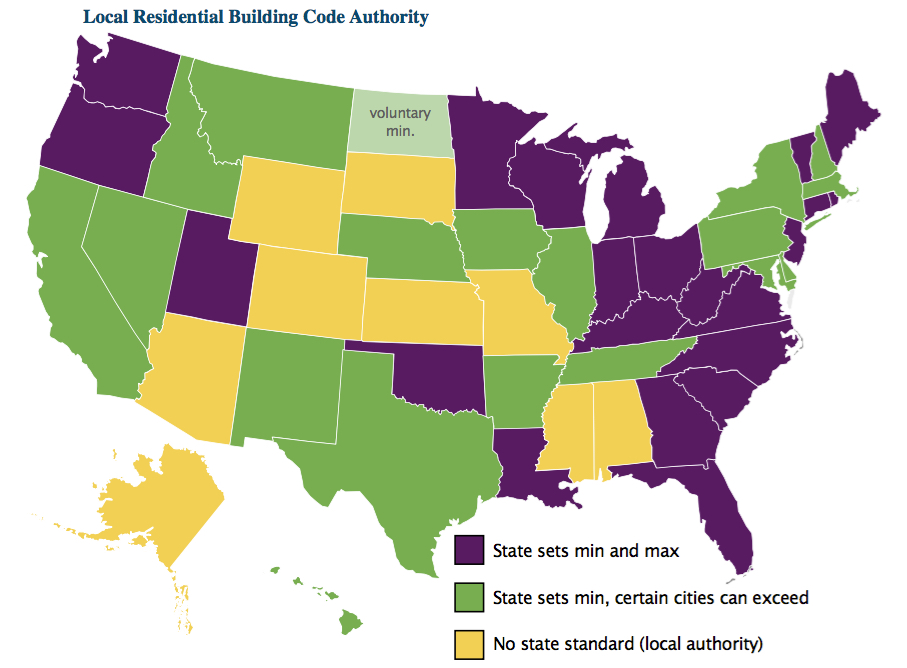

Updating building codes is one of the most certain ways to implement new changes and requirements into a city’s building sector, making ZNE building code requirements an obvious method for transitioning to ZNE. However, local governments’ ability to change city building codes depends on state building standards.

Many states either set a minimum building code standard that may be exceeded by higher city standards, or do not set a state standard at all, relying instead on local authority to implement building codes. In the 28 states with no state building code cap, it’s up to city government to pass a ZNE building code. The other 22 states set the minimum and maximum building standards for the state, which makes passing a ZNE building code a state level endeavor.

While changing state building standards often involves more coordination, planning, and time than changing city building codes, state level changes can and do happen.

California presents a good example of building code change at a state level, considering it was the first (and so far only) state to adopt ZNE goals. The CPUC and its regulated utilities released the California Long Term Energy Efficiency Strategic Plan in 2008, which outlines plans for raising statewide awareness of ZNE, educating industry professionals about ZNE, ensuring availability of the necessary technical tools, creating finance and affordability plans, readying the grid for ZNE, and aligning state policies, incentives, and codes — all before 2020 when the new ZNE building code is implemented.

No Code? No Problem

Because building codes only establish minimum requirements, buildings can be as energy efficient and solar friendly as possible, as long as they comply with state and city code. Even in states where state ZNE building codes may be years away, local builders, cities, and individuals can voluntarily adopt ZNE.

Since 2012, the Fort Zero Energy District (FortZED) project has tested the processes of transforming the 2.5-square-mile downtown district of Fort Collins, Colorado, into a ZNE district. With local funds of $5 million and a $6.3 million grant from the DOE, the FortZED project has reduced residential and city building energy use, helped install renewable energy systems, helped to reduce peak energy demand by 20%, and tested a number of other technologies providing information on the feasibility of microgrids and distributed energy generation. The FortZED project has run successfully for several years even though Fort Collins does not officially have a ZNE ordinance on the books.

Hundreds of single-building ZNE projects also exist in cities and states without ZNE goals or codes. The NBI library of ZNE case studies, presents a number of examples of ZNE residences, schools, libraries, and commercial buildings that have achieved ZNE without city building code requirements.

Folding ZNE into the Clean Energy Economy

With modern technology, ZNE buildings are now in a position to enter into the mainstream and set a new standard for energy consumption in the building sector. When states and cities commit to ZNE rules and goals, they propel the clean energy economy. In turn, community members can capture the savings and benefits of reduced energy consumption and distributed energy generation. Individual builders and community members can also lead the way to zero by adopting ZNE, one project at a time. As more cities look for innovative ways to curb energy use and promote renewable generation, ZNE deserves a close look. The path leads to zero.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers via Flickr (CC 2.0)

For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter or get the Energy Democracy weekly update.

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.