What If…Your Electric Utility Was A Benefit Corporation?

Originally published at ilsr.org. This article was originally written by former ILSR Research Associate, Matt Grimley.

The misunderstandings that from time to time occur between communities and the managers of electric-lighting companies will, to my mind, disappear entirely if the relations between the two are correctly founded on the basis of public control, with corresponding protection to the corporations operating this industry.

More than 100 years ago, standing in front of a crowd of investors, Samuel Insull articulated his vision for a responsive and responsible electric utility.1

Fresh from building his own electric utility empire from Thomas Edison’s companies, Insull wanted his electric industry recognized as a natural monopoly with competition viewed as a threat the public good. Public regulation, he argued, would provide a reasonable and steady profit to the monopoly utility, while economies of scale of power plants would allow the utility company to deliver increasingly inexpensive electricity in service of the public good.

A century later, only half of Insull’s rough vision has come true. Most of today’s investor-owned electric utilities retain their century-old monopoly, but insufficient regulation has often left the public good by the wayside. Instead, investor-owned electric utilities (IOUs) have kept a laser focus on shareholders’ returns. They have built large, unnecessary fossil-fueled power plants when more energy-efficient approaches would cut consumers’ costs. They try to change electric rates in ways that harm the poor and elderly, then use public funds to help the indigent pay their bills. They spurn rooftop solar and customer-owned power generation.

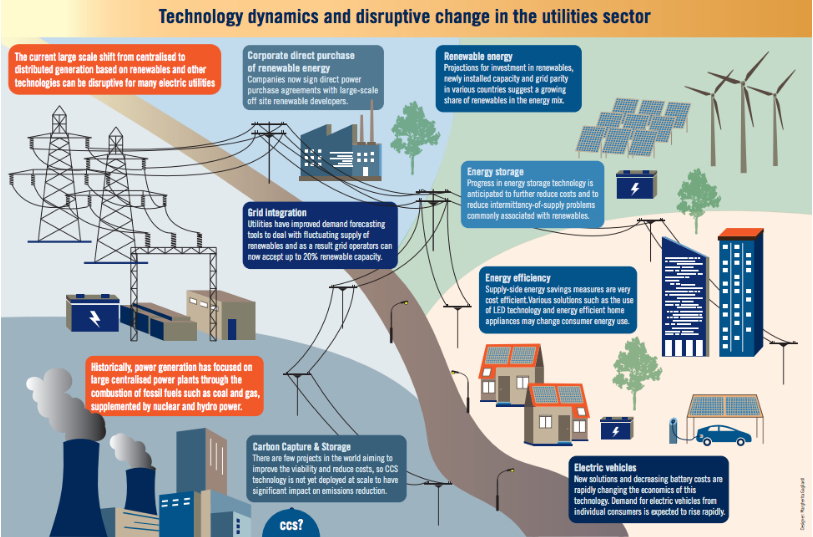

In some sense, this behavior is no surprise. The regulatory scheme Insull imagined shaped two key profit motives for utility companies: selling more power and building more infrastructure. But neither makes sense any longer. Electricity demand has leveled off, and distributed, non-utility power generation is often less expensive than relying on utility shareholder capital.

Adding insult to the injury of the public good, investor-owned utilities frequently lobby against legislation in the public interest, from renewable energy to energy efficiency standards to community solar programs. They use their publicly-granted monopoly profits to oppose the public interest.

One new model is emerging, however, that offers an alternative to the traditional investor-owned utility, and aligns with the fantasy of Insull’s original vision to simultaneously protect the public good. It’s the B Corp.

Green Mountain Power B-lines into a B Corp

In 2014, one electric utility in Vermont shuffled away from historic investor-owned electric utility trends. Green Mountain Power transformed itself into a B Corp, a designation that cements its commitment to sustainability, transparency and accountability. The certification, administered by nonprofit B Lab, mirrors legislation in most states allowing businesses to become “benefit corporations” that uphold similar goals.

A benefit corporation is an alternative corporate structure. Essentially, it changes the for-profit corporation, which may consider the public interest, into one that legally must pursue greater social goods and regularly report to shareholders on its progress. Failure to do so could trigger a shareholder lawsuit.

It was an easy decision for Green Mountain Power to join the well over 1,000 corporations publicly committed to working toward the public good. The company wanted to “become the Ben and Jerry’s of the utility world,” according to CEO and President Mary Powell. The ice cream giant, also a B Corp based in Vermont, won praise in the late 1980s for putting its social mission on par with its economic goals.

More than anything, Green Mountain Power’s move reflected its embrace of changes (and threats) to the outdated, centralized business model still used by many electric utilities.

But unlike many of its counterparts, Green Mountain Power helped expand net metering across its home state. It also fronts the cost of retrofitting homes with solar and energy efficiency products (paid back via the utility bill) in a program that generates substantial cost savings for households. Green Mountain Power also built one of the nation’s first all-solar microgrids, and finances energy storage for customers.

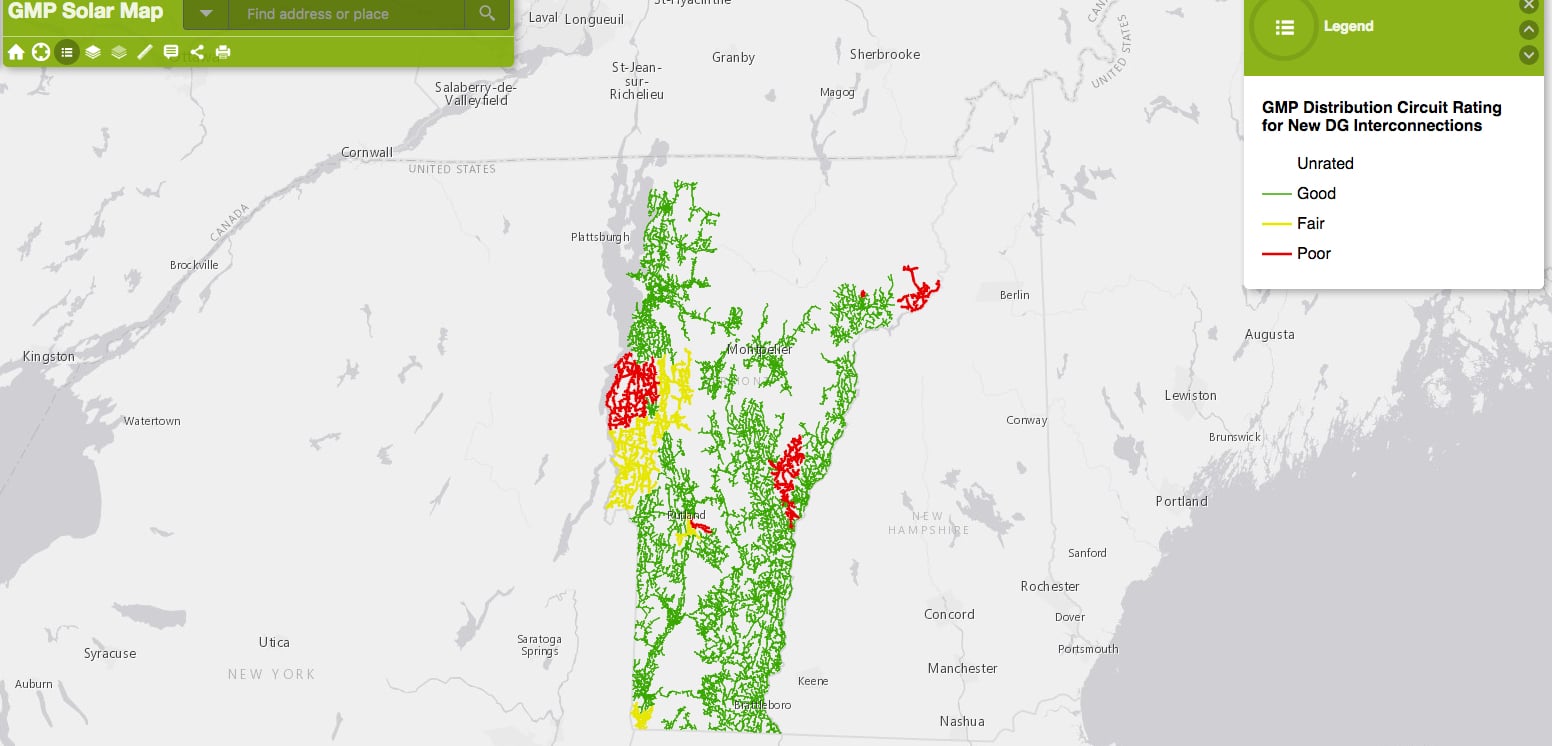

The utility, has mapped out its distribution circuits (shown below) to help solar developers see where’s there’s room to grow. Even while adding more renewable energy to its fuel mix, Green Mountain Power has lowered its electric rates three times in the past four years.

As a vertically-integrated utility, Green Mountain Power controls everything from power plants to the distribution wires that connect to homes. But it decided to turn its gift of monopoly control into the “un-utility,” Powell says, to “really become an organization that was fast, fun, and effective.”

It was a culture shift that enabled the change.

Powell works in the same “colorful Costco” of an office as everyone else. Workers can come and go as they please. Everyone understands that the customer is at the core of the business model — a far cry from the conservative culture of most monopoly, investor-owned utilities, which prioritize shareholder value over the public interest in a decentralized renewable energy future.

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast every day,” says Powell.

Like what you’re reading? Listen to our podcast with Mary Powell!

The numbers tell part of the story.

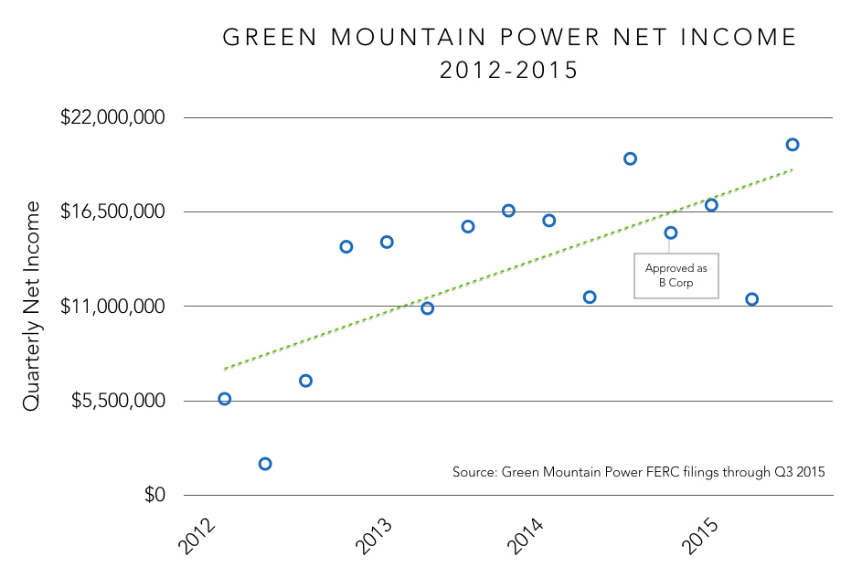

Since Green Mountain Power sealed its B Corp status in late 2014, its net income — a central metric used to gauge the utility’s financial success — has not wavered from its general upward trajectory. The leadership at Green Mountain Power doesn’t expect that to change.

Gaz Metro, the Canadian energy firm that bought Green Mountain Power several years ago, has enjoyed a healthy run so far, Dorothy Schnure, a spokesperson for the Vermont utility, told ILSR in June. But those benefits have not shortchanged customers or the public interest.

“We want to keep a very stable rate path, and we want to earn healthy and stable returns for our investor, which we have done,” Schnure said. “Our approach has been if we serve our customers really well and we delight our customers and we look out for our customers, our investor’s going to be OK.”

Green Mountain’s leap to B Corp certification was a natural one. For years before, the utility had focused on policies supporting its customers and their communities. Company leaders insisted on upholding this corporate philosophy through acquisition talks with Gaz Metro a decade ago, when they made clear that the Canadian company’s parent — pipeline operator Enbridge, hotly contested for its environmental impact — needed to stay on the sidelines.

“Before we agreed to that purchase, we did a lot of due diligence in making sure that Gaz Metro’s philosophy would align with ours and that we would be able to continue working as a deeply conscious and socially-conscious entity,” Schnure said. “That’s how we operate and it’s part of what makes us so successful.”

Green Mountain Power might have been well-positioned to pounce on the B Corp process, but that doesn’t mean the utility’s work is done. To keep the certification, it must submit annual reports that support its status — a motivator, Schnure said, for Green Mountain Power to deepen its focus on sustainability and accountability.

B-coming a B Corp

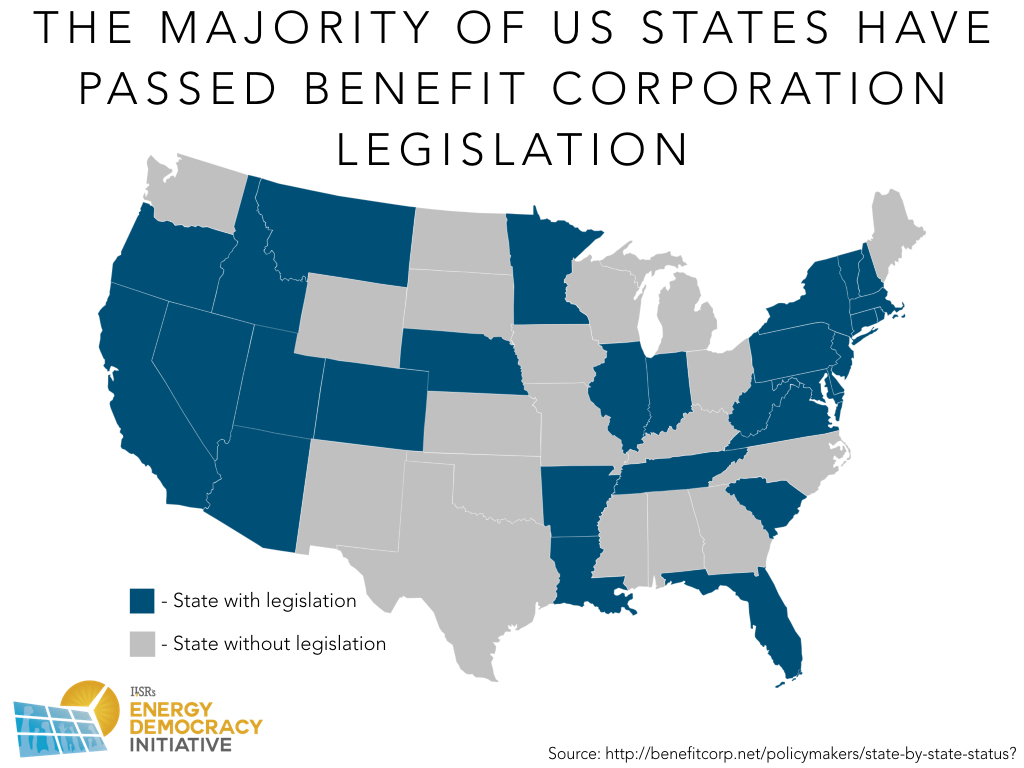

Though Green Mountain Power is still the only utility to secure B Corp status, the path is open to other utilities doing the same. A utility can become a B Corp in any state, and most states offer legal “benefit corporation” designations.

Depending on the type of structure a company has, the process for solidifying a commitment to social good may include:

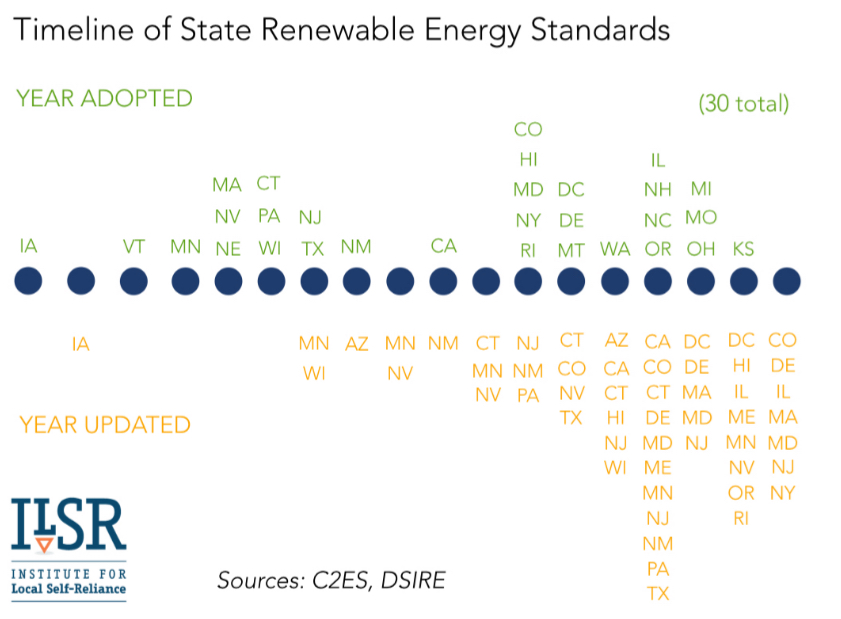

- Seeing if its home state has the legal framework to incorporate benefit corporations. To date, 30 states and the District of Columbia have adopted such legislation.

- Following the state process to become a benefit corporation. This usually includes amending its governing documents, then sealing support from a majority of shareholders to ratify the change.2 State filing requirements for these amendments are usually identical to tweaks related to any other corporate structure.

- Seeking the rigorous B Corp certification from B Lab, with or without the legal structure of a benefit corporation. The differences between a benefit corporation and a B Corp are listed here. Hint: the legal structure and certification are complementary.

There are more than 3,000 benefit corporations in the world. Of those, there are more than 1,600 benefit corporations registered as B Corps, spanning 42 countries and 120 industries.

B-lieving the Difference a B Corp Makes

Benefit corporations must do things differently than their brethren. If every utility were a benefit corporation, a number of utility actions over the past year might have played out differently. Note that this is not a wish list — benefit corporations must consider public goods.

Structuring as a B Corp or a benefit corporation isn’t a perfect antidote, even for companies considered beacons in the movement like Green Mountain Power. The Vermont utility has fielded blowback in the spring from people who live near an industrial wind project that one critic said is noisy enough to drive down their quality of life and erode home values.

In a letter to the editor published in the Manchester Journal, she questioned whether Green Mountain Power was responsibly building wind infrastructure, or if the the company was simply expanding its power-producing assets to boost its bottom line — a familiar strategy for investor-owned utilities.

Still, the B Corp and benefit corporation designations send a notable message and carry an unmistakable upside that — if widely adopted in the entrenched energy industry — could improve the way utilities engage with consumers.

For example, under a benefit corporation structure, it would have been tougher for NV Energy to lobby the Nevada Public Utilities Commission in 2015 to cut net metering rates, including a controversial retroactive measure that reduced reimbursement rates for already-installed projects.

Beyond triggering smaller payments for more than 17,000 Nevadans, the move pushed several solar developers out of the state. The utility justified its campaign by pointing to costs of net metering, but as a benefit corporation, it would have had to also factor in widely acknowledged benefits. Instead of lobbying to cut solar energy, the utility could have fought for it.

Then, in the spring of 2016, the Public Service Commission in Washington D.C. voted 2 to 1 to approve Exelon’s merger with Pepco — a decision that defied the mayor, numerous stakeholders and even its own prior order. Mergers aren’t unusual in the utility world, especially after the past two decades of unraveling anti-monopoly legislation.

But the consolidation trend exposes conflicts between public and private interests, showcasing the toll these deals can take on the public. With Exelon and Pepco, most criticism boiled down to Exelon needing to support its own generation with Pepco’s captive customers. Still, after a two-year fight, the transaction was finalized in June. Opponents plan to sue.

Given a benefit corporation law such as the one in play in Delaware — the most common place for US businesses to incorporate — Exelon and Pepco directors would have had to consider all corporate constituencies in their merger application, not just stockholders and the highest bidder.

And then there’s Xcel Energy. After more than three years, and with almost 1,000 applications in the queue, the utility’s community solar program has only three solar garden up and running.

Calling it a “slow start” is understatement that sidesteps Xcel’s delay tactics. First, the utility rejected a value-of-solar pricing program intended for the community solar gardens. Then it refused to answer developer questions about grid location and muddied co-location rules of projects. Even after it started approving applications, Xcel continues to keep technical and financial information from community solar developers.

A community solar law took effect in 2013, but has been slowed down by Xcel Energy ever since. A benefit corporation likely wouldn’t have waited this long. By force of its structure, it could have prioritized the public benefit of the value-of-solar methodology. It could have treated the grid as a commons, freeing up information to solar developers — like Green Mountain Power did — instead of flexing its monopoly power.

It’s not that slapping a B-Corp label on a utility will make it good, but it will give the public additional leverage to demand the utility consider broader interests than its own.

Digging B-low the Surface

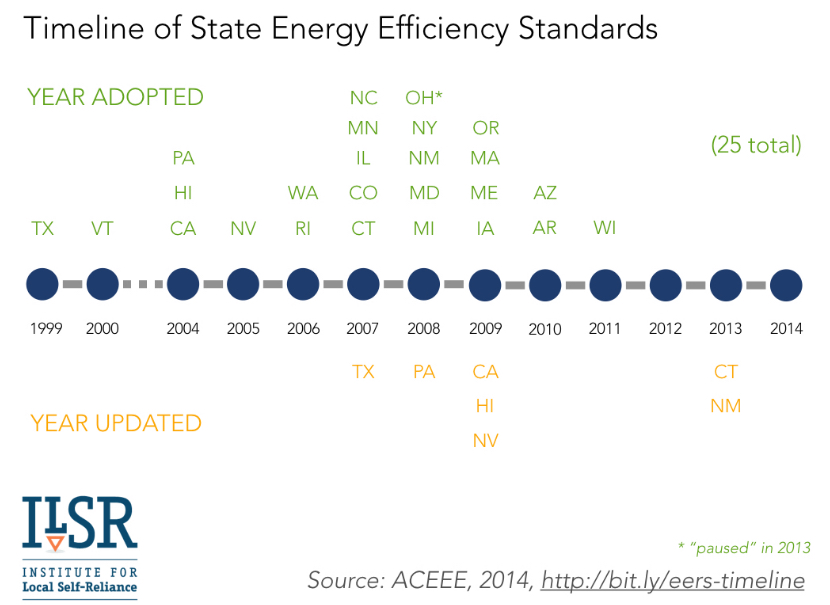

A shift toward the B Corp mindset aligns with a swell of public support for rules that favor energy efficiency and increased reliance on renewables. Largely over the past two decades, lawmakers in states nationwide have adopted standards for efficiency and renewable production — both key tools in the fight against climate change.

In recent years, Maryland regulators boosted energy savings targets for utilities in their state while California agreed to double its energy efficiency savings goals by 2030. Plus, a recent report from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory shows states’ aggressive renewables policies — increasingly popular nationwide — deliver distinct benefits without driving up costs.

But it’s not just the public that want electric utilities to change. In the last year, there has been a rash of electric utility shareholder initiatives, all directed toward making their companies more sustainable:

- Shareholders of Madison Gas & Electric submitted a proposal to force more renewable energy generation, that was eventually withdrawn after the utility agreed to increase its use of renewables and collaborate with shareholders to evaluate opportunities to expand its renewables business

- Nextera Energy shareholders, facing opposition from the company, crafted a resolution for the to company consider sea level rise even as it reinforces old power plants built along the Floridian coast

- 8.5 percent of Ameren shareholders in May 2016 voted for a resolution requiring the company to adhere to a 30 percent renewable energy standard by 2030 — not enough support for outright approval, but enough to keep it on the ballot at next year’s shareholder meeting

- Nearly 40 percent of Entergy shareholders recently demanded that the utility increase distributed, renewable energy throughout its territory

According to a report from the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, electric utilities and their business models face a growing number of liabilities, shown below:

Customers and shareholders of electric utilities want them to change in the public interest to address these risks. Regulators want them to change. Legislators are tired of the utilities’ pushback.

Most electric utilities are culturally and structurally reluctant to consider anything beyond shareholder returns, but they don’t have to be. Green Mountain Power shows that there’s a way to reconcile shareholder and the public interest, and that retaining a utility monopoly could make sense even if it’s no longer a natural monopoly.

Maybe it’s time for a Plan B.

This article originally posted at ilsr.org. For timely updates, follow John Farrell on Twitter or get the Energy Democracy weekly update.

More Information:

- Bradley, Robert Jr., “The Insull Speech of 1898: Call for Public Utility Regulation of Electricity (The origins of EEI’s support for cap-and-trade in today’s energy/climate bill),” Master Resource, April 29, 2010, https://www.masterresource.org/edison-electric-institute/the-insull-speech-of-1898/.

- The important text added to the governing documents usually includes: “… [The Director] shall give due consideration to the following factors, including, but not limited to, the long-term prospects and interests of the Company and its shareholders, and the social, economic, legal, or other effects of any action on the current and retired employees, the suppliers and customers of the Company or its subsidiaries, and the communities and society in which the Company or its subsidiaries operate, (collectively, with the shareholders, the “Stakeholders” ), together with the short-term, as well as long-term, interests of its shareholders and the effect of the Company’s operations (and its subsidiaries’ operations) on the environment and the economy of the state, the region and the nation.”

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Latest CleanTechnica.TV Video

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.